Posted on: Tuesday December 3, 2024

We’ve all had the experience of reading something when a word, a name, or a concept piques our curiosity and sets us off on a research quest. This often happens when I am working with human history collections at the Manitoba Museum and regularly inspires my inner ‘Nancy Drew’.

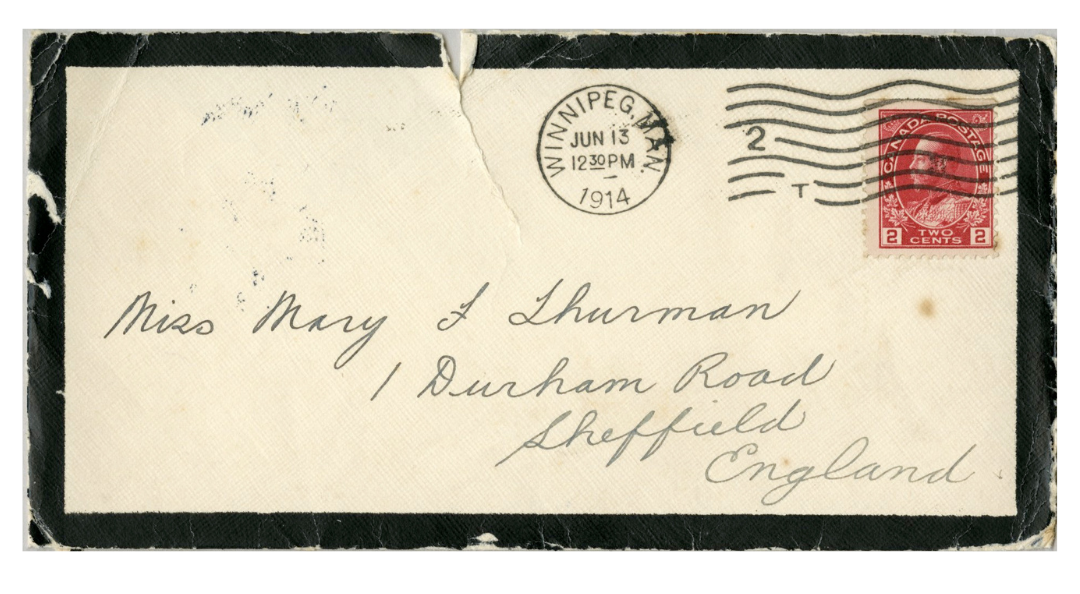

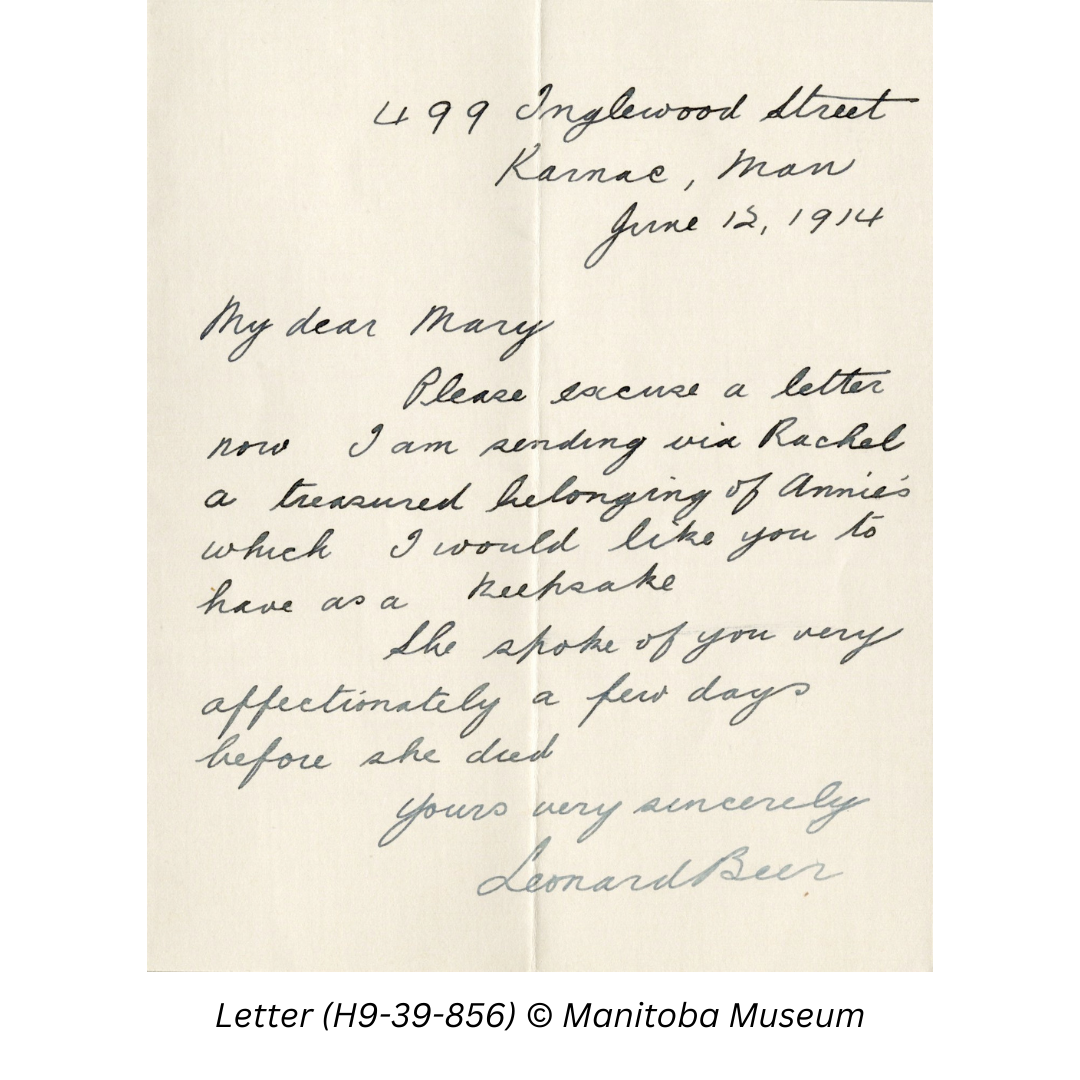

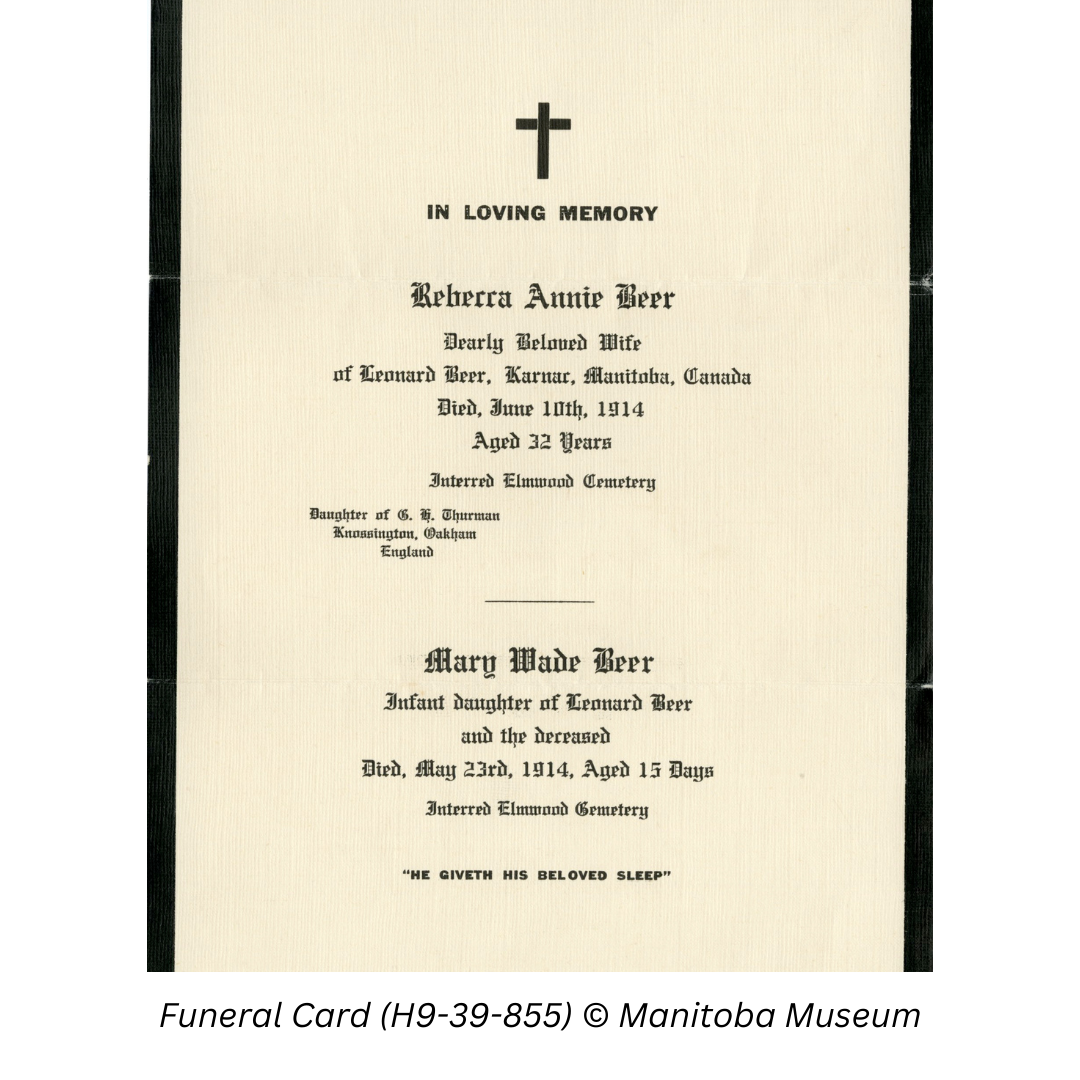

One such search started with a donation mailed from England. About 40 years ago the donor had purchased a box of old cards and letters for a few pence in a second-hand shop. Amongst them was a black-bordered letter sent by Leonard Beer to Mary Thurman in Sheffield England, dated June 1914. Sadly, the letter contained a funeral card for Leonard’s wife Rebecca Annie and their infant daughter Mary. Leonard lived at 499 Inglewood, Karnac, MB. The donor asked if we knew where Karnac was located as he was unable to find it on a map.

A quick search of reference books on Manitoba geographical names didn’t turn up any results, past or present. Fortunately, we live in a world with vast on-line resources at our fingertips. The next step was a quick Google search for Karnac which naturally turned up thousands of hits for the famous Karnak temple complex near Luxor, Egypt. It is not unusual for Manitoba communities to be named for places all around the world.

But what about “Karnac Manitoba”? Far fewer hits this time including a site with a list of WWI soldiers, one of whom gave an address on Parkview St., Karnac. There were also some Free Press classified ads listing a Karnac address.

My next search led me to an on-line library that includes a digitized copy of a 1926 publication titled Distribution for Manitoba and Saskatchewan. The book contains lists of post offices and rail distribution schedules for mail from Fort William. I didn’t find Karnac where it should have been after Kaleval and Kane but before Katrime and Kawende. It was there however, on the “Nixie” List for Manitoba. Nixie was the designation given to post offices that had been closed. Karnac mail was now to be sent via Winnipeg.

Now I knew that Karnac was not a community but the name given to a post office district. On Library and Archives Canada’s web site I came across a feature on postal history with data base of Post Offices and Postmasters. The Karnac post office, located at 1841 Portage Avenue, was opened on May 1, 1913 and operated until June 26, 1923. For the first four years, Ralph R. Magee served as the postmaster. Following his resignation, the position was filled by A.J. Perrie until closing.

Another great resource for researching local history are the annual Henderson directories for the City of Winnipeg. They are a great way to explore changes in older neighbourhoods in the city and perhaps find out who used to live in your house. Our Karnac Post office first appears the 1914 edition. That year, in addition to the main post office at Portage and Garry, there were 32 sub offices and suburban post offices. Most had only a letter or number designation but some like Norwood Grove, Grand Vital and Morse Place survive as neighbourhood names. Others such as Karnac, Dickens or Derry may be less familiar to us today.

The Karnac Post office was located near the corner of Roseberry St. where today you will find the Good Earth Restaurant. The block from Roseberry to College was home to numerous shops including John Watson Co. Grocers at 1849 Portage, while Ralph R. Magee, ran the post office and a drug store next door at 1849-1/2. By 1918 at Harold Harris operated the grocers and Alex J. Perrie was the new druggist and postmaster. According to The History of Pharmacy in Manitoba, 1878-1953 Percy Braund opened the first pharmacy in St. James at the corner of Roseberry and Portage in 1910. Ralph Magee was the first manager and he purchased the business in 1913. He was succeeded by Alex. J. Perrie ran Perrie’s Pharmacy until he retired in 1945.

On May 1, 1913 the Winnipeg Free Press had reported that a new post office would be opening in St. James, “in R. Magee’s drug store at the corner of Roseberry street and Portage Avenue”. Known as the Karnac post office, it was intended to serve “all the district lying between Brooklyn and Rutland streets”. This would be the third post office in the area along with the St. James post office and the King Edward at the Winnipeg city limits. Readers were reminded that they should add the proper post office to the address rather than just name and St. James or a street address and ‘city’ in order to avoid a delay in mail reaching its destination. That would explain why our letter writer, Leonard Beer, used Karnac as his return address.

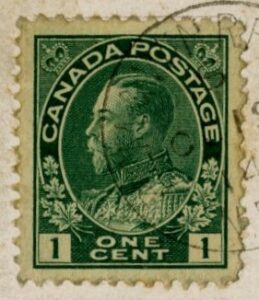

The same article mentioned that “the residents of St. James would like to draw the attention of their Winnipeg correspondents to the fact that letters sent to them require a two-cent stamp as St. James is not in the city” where only a one-cent stamp was needed. Residents of St. James often “have to pay two cents extra before they can receive their mail on account of only a one-cent stamp being on the envelope.” On March 17, 1916 the paper reported a change in policy meant that “all territory adjoining the city has been taken into the Winnipeg postal area.” Postage rates within the city had doubled to 2¢ but the 1¢ surcharge to mail a letter from Winnipeg to Karnac was no longer required. Readers could also look forward to letter carrier delivery in the future.

In the end, a simple question from a donor about an unusual place name led me to some interesting postal and neighbourhood history. Along the trail, I also discovered the Karnac Picture Palace or the Karnac Theatre, not far from the post office at 334 Roseberry and Ness Ave. It appears to have operated from 1915 to 1920. But that will have to be a case for another day.