Posted on: Tuesday May 13, 2014

By Kathy Nanowin, past Manager of Conservation

Well, after thirteen years or so, the Museum’s conservators are back climbing in the Nonsuch rigging, in order to check and clean the lines, sails and masts. This is a very exciting development for Collections and Conservation.

A bit of background information – amendments to Manitoba’s Workplace Safety and Health regulations in 2002 resulted in stricter requirements for workers climbing at heights. The Nonsuch therefore had to be provided with fall arrest lines, in order that workers could safely climb up in the rigging. The Manitoba Museum worked for the next several years to design, cost and install appropriate safety lines from the gallery ceiling. Additionally, the staff who would be doing the climbing had to take Fall Arrest training; and the Museum had to have a written Safe Work Procedure detailing how the climbing will be done.

Finally, everything has been put in place, including the purchase of safety harnesses designed specifically for women, as the two conservators who will be climbing are both female.

Conservator Carolyn Sirett was the first to go up and look at how dusty the main yard and mainsail were (very dusty!). She then came back down and we decided that she could carry up the backpack vacuum that is normally used to clean on board the ship.

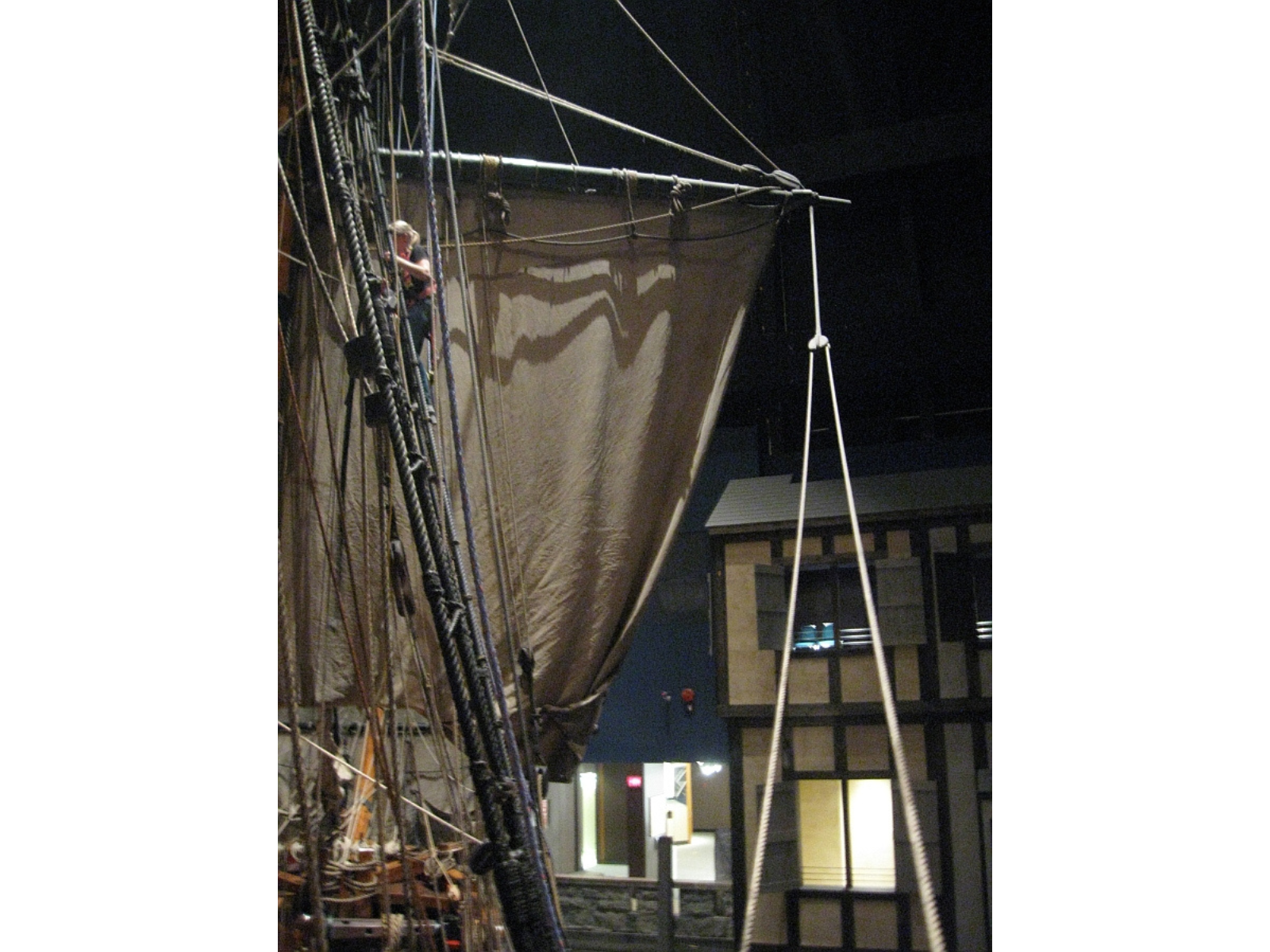

Carolyn on her first climb.

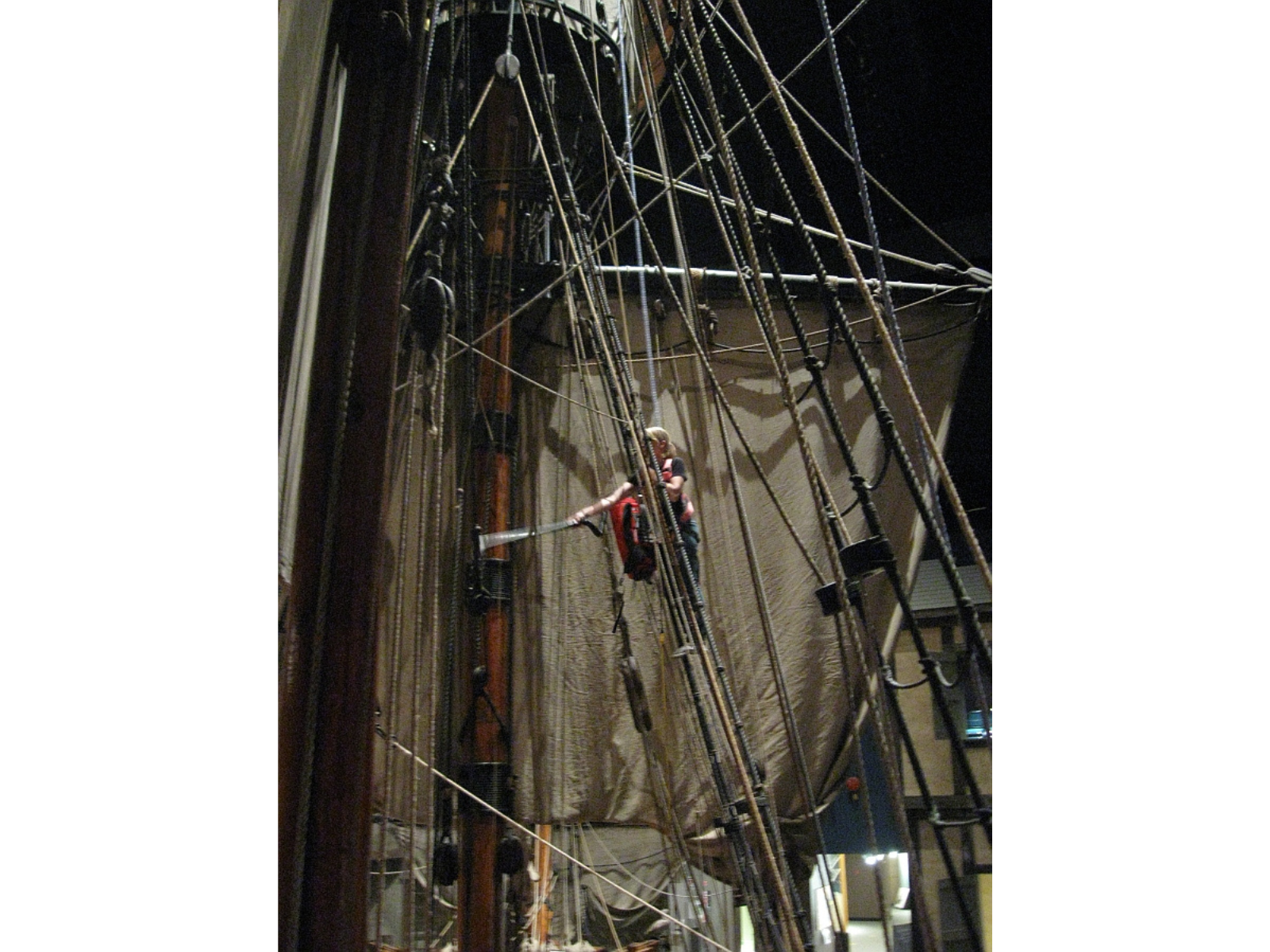

Carolyn starts to climb with the vacuum.

Here she is partway up the ratlines.

Carolyn was able to vacuum most of the dust off the starboard side of the mainsail, main yard and the footropes on the main yard.

We will continue to climb up in the rigging as time allows. Mondays during winter hours are best, as it takes time to prepare – check harnesses, get supplies – and we can’t let any visitors on board while someone is working aloft. The Museum will soon be moving to summer hours, so after next week, the work will most likely stop until the fall.

In future, instead of hauling a vacuum up into the rigging, we will be using a converted central vacuum that belongs to the Planetarium/Science Centre. It has a 50-foot long hose, so only that will have to be carried up; it will be much easier.

Image: Vacuuming the main mast.

We will continue to clean off the Nonsuch rigging over the next fall/winter season. Dust can be damaging as well as unsightly, so it should be removed whenever possible. I hope to post some before and after images that will really demonstrate how much dust we’ll be dealing with!