Posted on: Thursday July 9, 2020

UPDATE 25 Jul 2020:

The comet has faded below naked-eye visibility but it still visible in binoculars as a small fuzzy patch. The tail has shrunk but it still visible in photos. With the moon entering the evening sky and the comet fading, this object is well past its prime. We’ll have to turn our attention to the upcoming Perseid meteor shower, which peaks on August 11th and 12th, and the planets Jupiter and Saturn, both visible in the southeast as darkness falls.

Comet C/2020 F3 NEOWISE has become the brightest comet in years, and it will be getting better this week. The comet is best seen in the early morning sky for the next few days, but quickly swings over into the evening sky, making it much more convenient for sky watchers to get a glimpse.

What is a comet?

A comet is a ball of ice and rock a few kilometers across, orbiting the sun in a very oval-shaped orbit that keeps it far away from us for most of its lifetime. When the comet nears the sun, much of the ice melts, and the dust and gas are released into a beautiful tail that streams behind the comet and away from the sun. There are a half-dozen comets visible in large telescopes at any given time, but it’s rare that we get one bright enough to see with the unaided eye.

Comet NEOWISE C/2020 F3 is named after the satellite that discovered it, and it needs extra numbers tacked on because the NEOWISE satellite discovers a lot of comets. (We’ll call the comet “Neo” for short in this article.)

“Neo” passed close to the Sun on July 3, which has caused an outburst of activity that makes the comet much brighter than expected. Although the activity should subside as the comet moves farther away from the Sun, the comet’s orbit actually carries it closer to earth until July 22. This closer distance may offset the lower activity. All of which to say, we have a bright comet to look at for the next two weeks.

As of July 9, “Neo” was visible to the unaided eye in the morning sky, and a nice sight in binoculars. Binoculars are your instrument of choice for viewing this object, because the comet’s tail too big to fit into the typical field of view of a telescope.

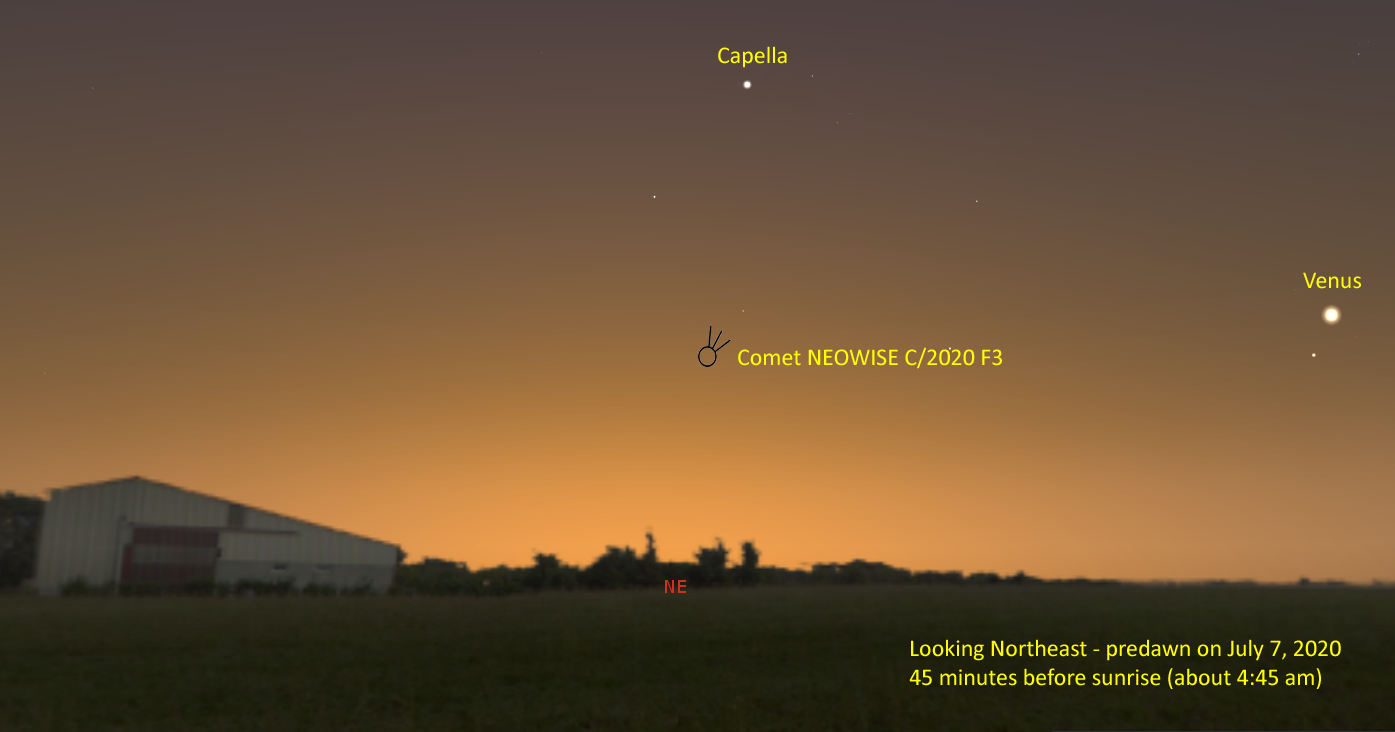

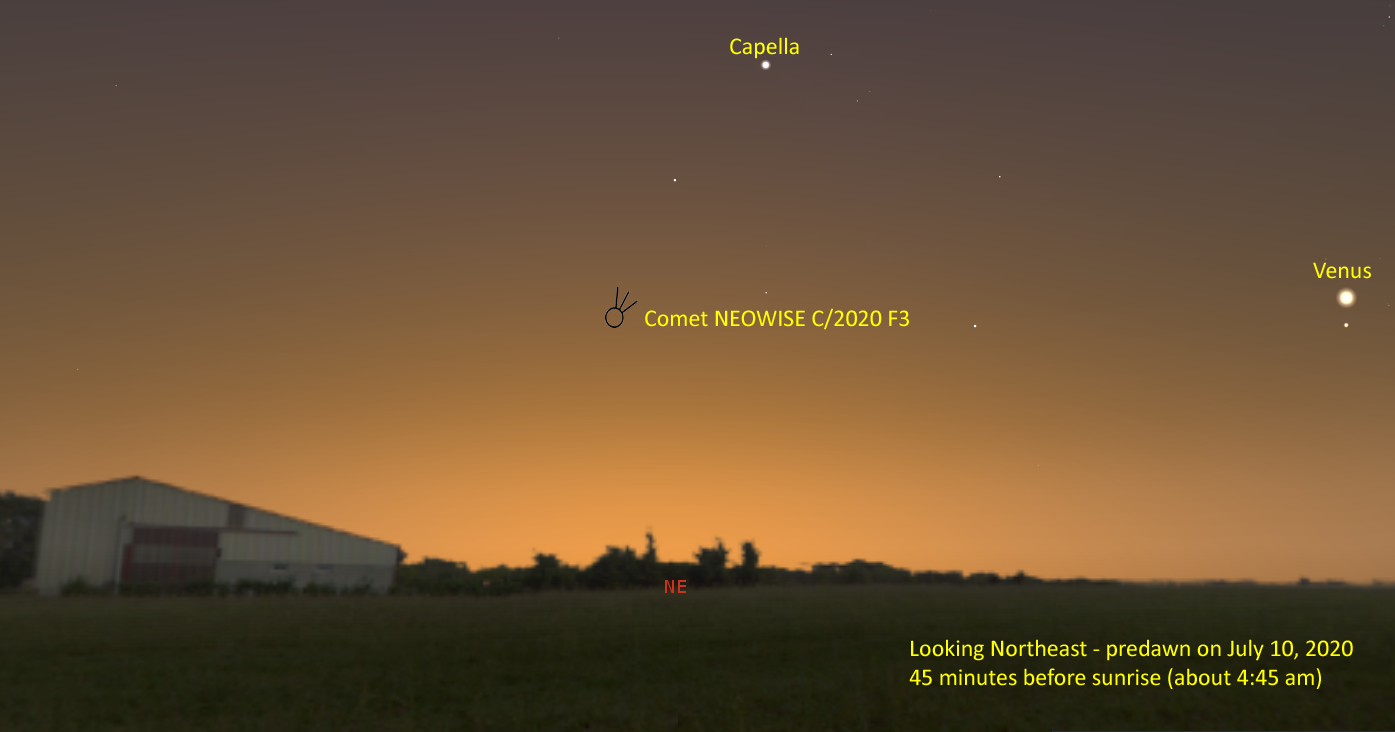

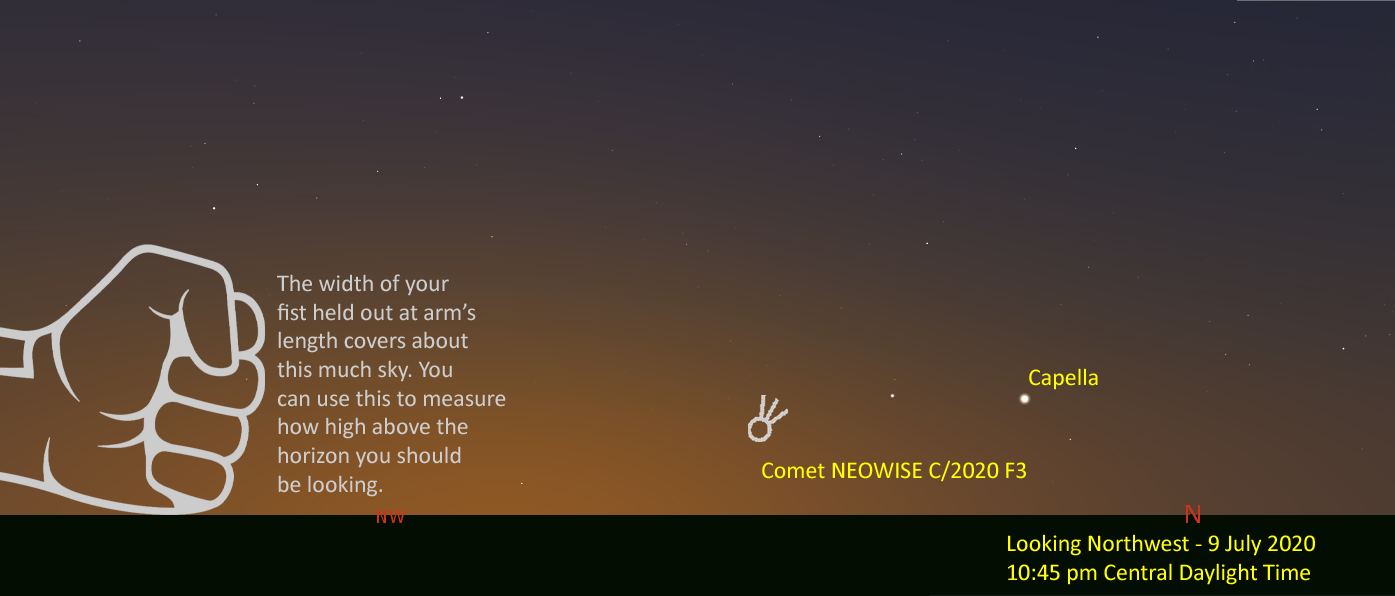

Due to its position in the northern sky, the comet is visible in both the evening and morning sky, although the morning views will be better until about July 11. After that, the comet’s rapid motion northward will make the evening views better (and more convenient). Use the charts below for the time you’re observing (we’ll add more as time goes on).

July 9, 2020 – 22:45

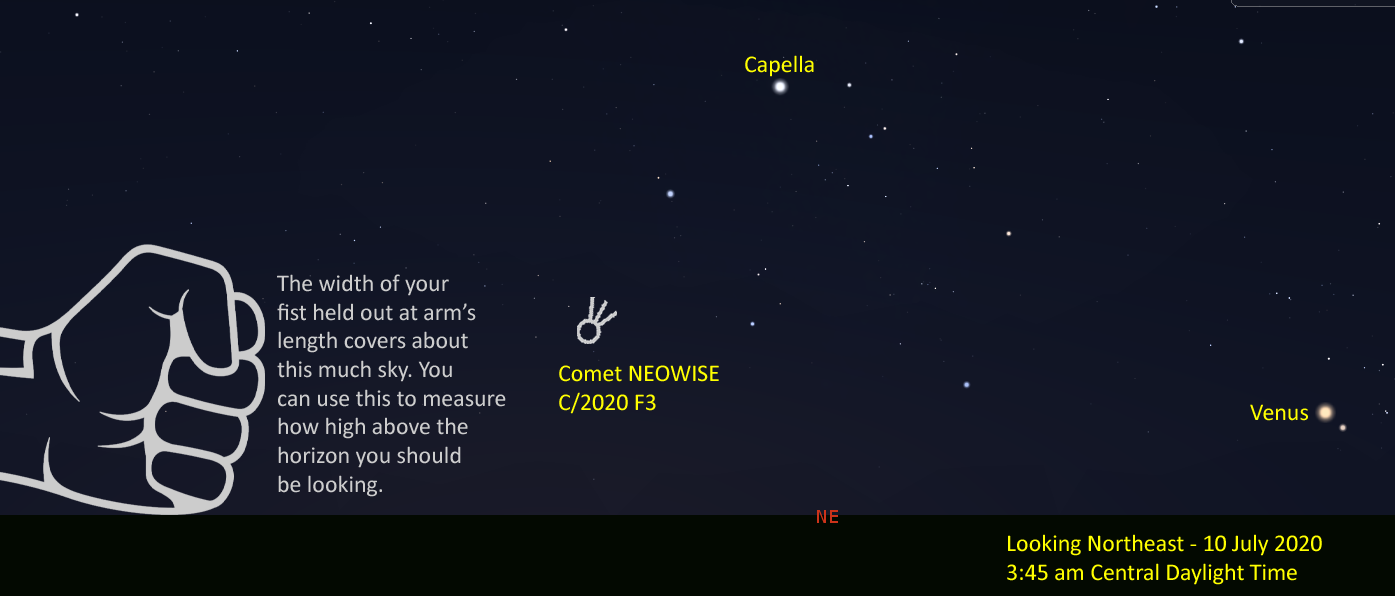

July 10, 2020 – 03:45

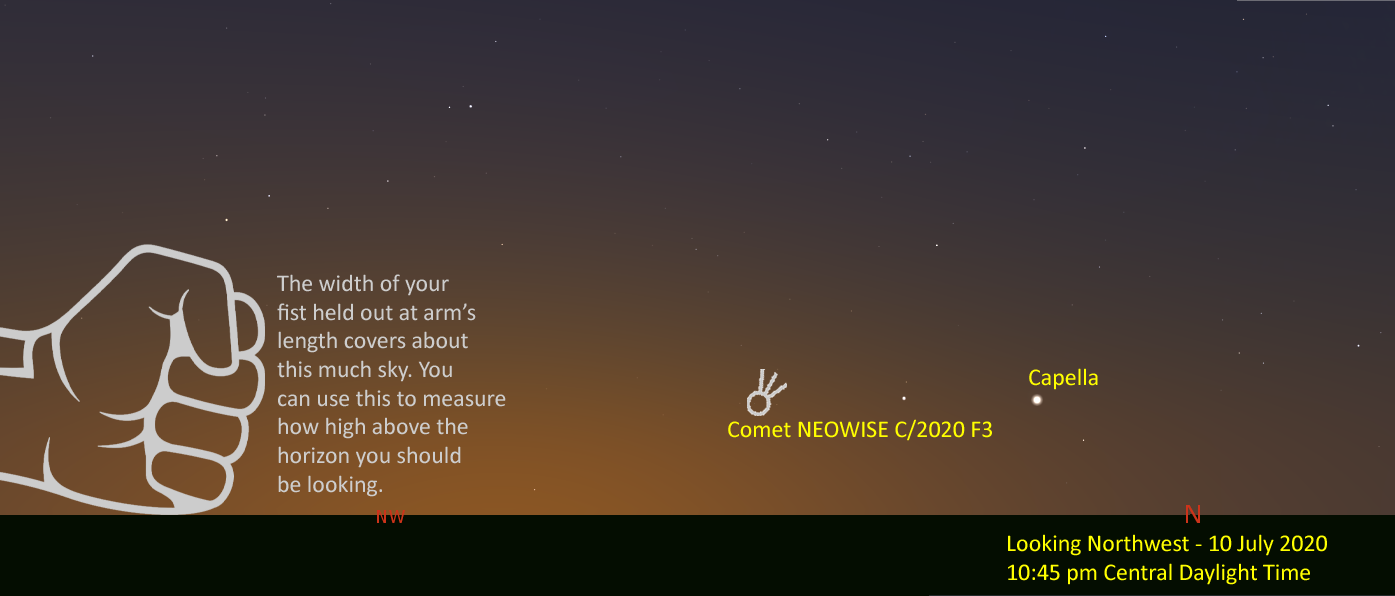

July 10, 2020 – 22:45

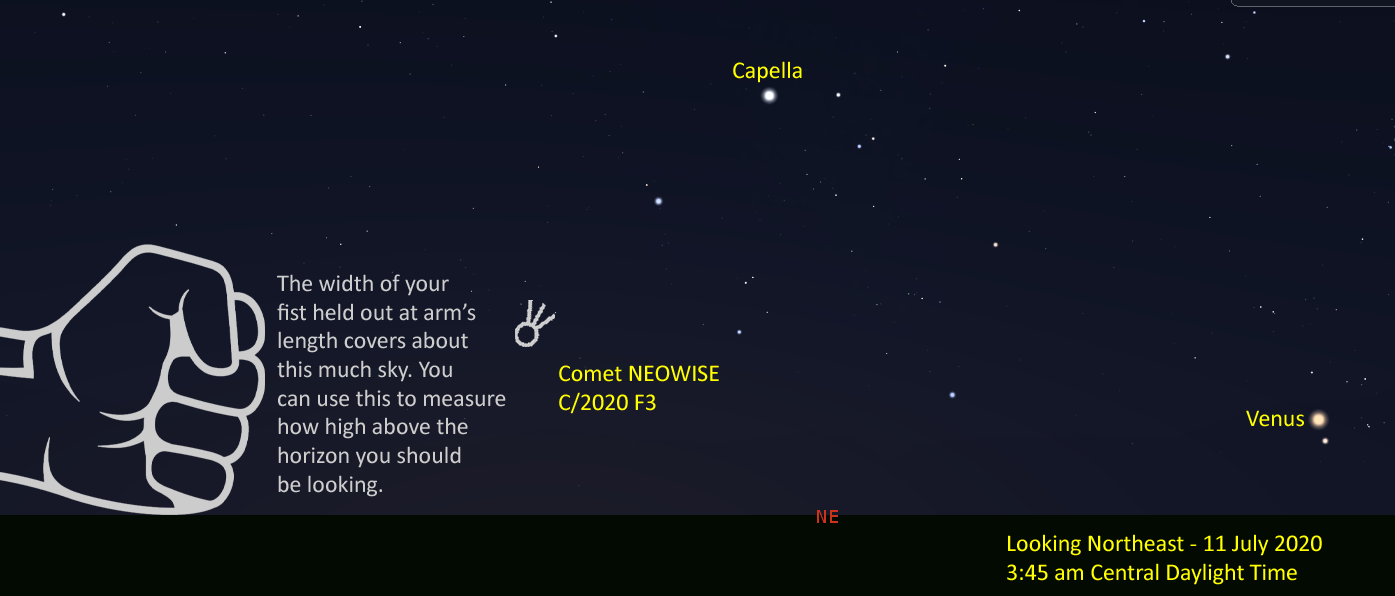

July 11, 2020 – 03:45

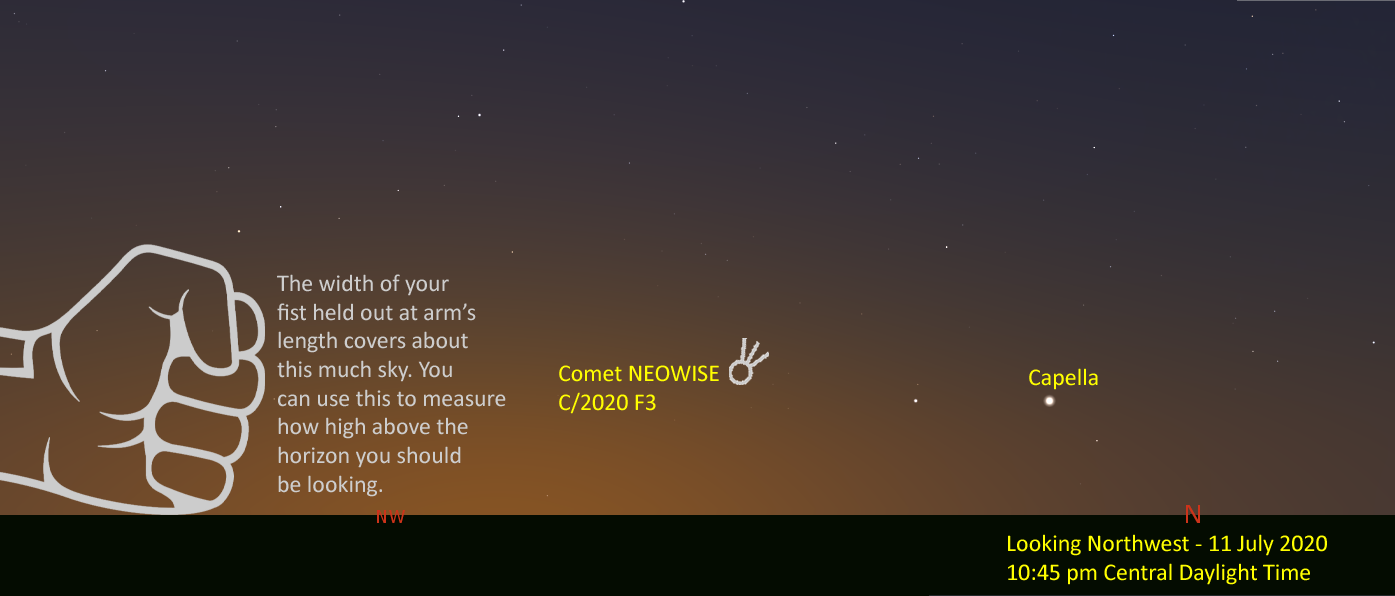

July 11, 2020 – 22:45

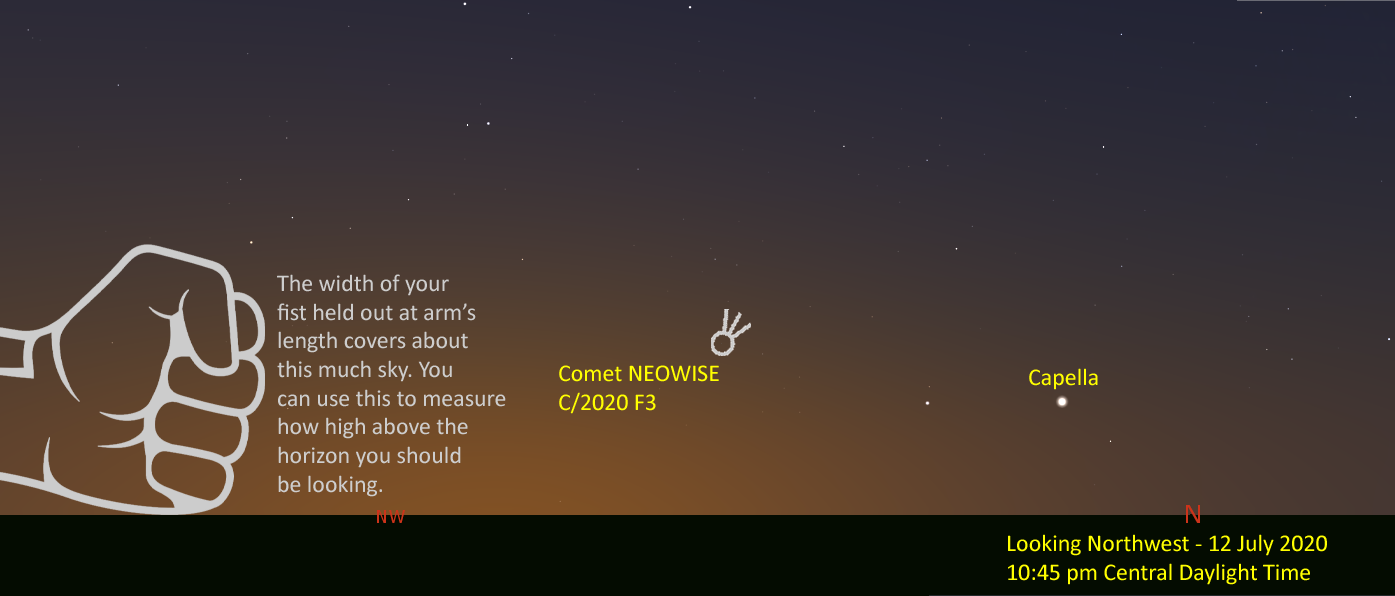

July 12, 2020 – 22:45

Sky charts created with Stellarium, a free astronomy software package available at http://stellarium.sourceforge.net.

How Do I See It?

First, consult the weather to make sure the sky will be clear, since any clouds will ruin your chances of spotting “Neo”. Use the local weather forecast, but also check out cleardarksky.org, which does special astronomy weather forecasts for thousands of locations.

Next, decide on an observing site. City lights, buildings, and other obstructions can make it hard to spot “Neo”. Get out of the city if you can, or at least to a location where you have a clear, flat northern horizon. If you’re observing in the evening, you want a good view to the northwest; morning observers need a good northeastern view. Bring along binoculars if you have them, and a camera and tripod if you have those. Both can help you spot the comet in the twilight whent he sky isn’t fully dark.

“Neo” moves, but not over the course of your observing session – it doesn’t flash across the sky (those are meteors). So, it will be in the same spot relative to the stars for hours at a time. Use the appropriate chart as a guide. Spot the bright star Capella first – it’s the best signpost to start from. (Morning observers need to make sure they don’t confuse Capella for much-brighter Venus, which is farther to the east.) Focus your binoculars or camera on Capella – the star should appear as a tiny sharp pinpoint, not a fuzzy blob.

Now, hold your first out at arm’s length. The distance from the bottom of your fist to your thumb spans about 10 degrees on the sky – so you can have a reliable measuring tool in the sky. One “fist” is marked to scale on each of the charts. The comet is generally one fist or less above the horizon, so make sure you don’t have any trees of buildings higher than that blocking your view.

Scan the area indicated on the chart with binoculars first – once you can see it in binoculars, it makes it easier to spot with the unaided eye.

If you are taking pictures, you’ll need to set your camera to manual, and take exposures of a second or more – hence the need for a tripod. It’s unlikely that camera phones will provide a great image, but try them anyway – you never know. The more you know about your camera and how it works, the more likely you’ll be able to get a good picture when the time comes, so break out the manual or find an online tutorial for your brand of camera.

Comets like this can appear at any time, but usually one a decade is about the expected rate. Get out and take a look before “Neo” fades away, which could happen before the end of July.

We’d love to see any images you get – tag them with #ManitobaMuseum or post them to our social media pages. You can find us on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Clear skies!