The Visible Planets

For planets, early morning is the time to observe. Although Saturn rises shortly after midnight, it stays low until the early morning hours. For unaided eye viewing you can catch it anytime after midnight, but telescope viewers should wait until it rises out of the thick murky (and probably smoky) air near the horizon for the clearest views.

Mercury moves into the evening sky this month, but the geometry keeps it very low to the horizon. It will be very difficult to catch even with binoculars, probably lost in the bright twilight after sunset. The best time to try for it is on the evening of July 7, when the thin crescent Moon will act as a pointer (see Sky Calendar below).

Venus reaches perihelion, the closest point to the Sun in its orbit, on July 10, but the same geometry keeps it very low in the west after sunset. What is the first day you can spot it with the unaided eye?

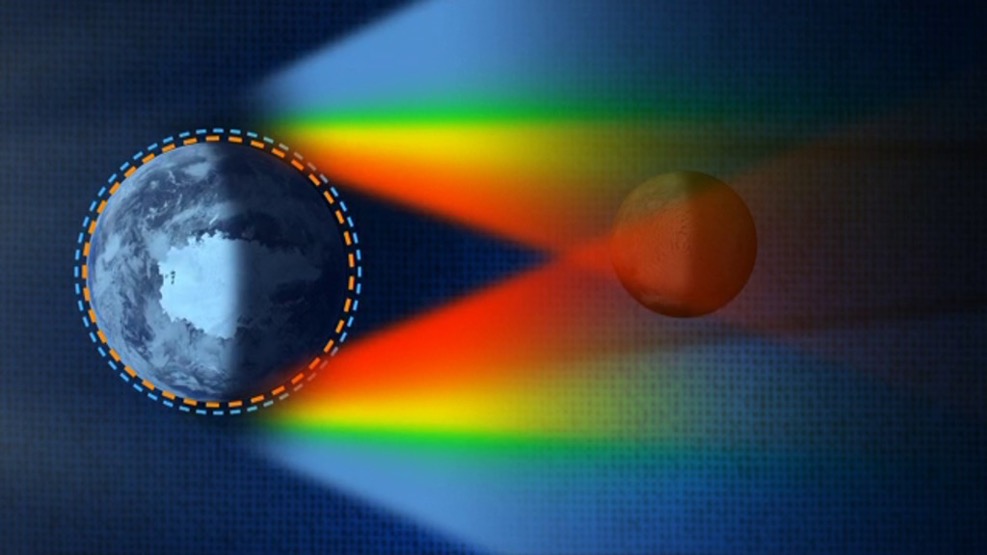

Earth reaches aphelion, the farthest point to the Sun in its orbit, on July 5. The slight change in the Earth-Sun distance doesn’t cause the seasons, but it does influence how long they are – this is why northern hemisphere summer weather (which occurs in July and August) is less pronounced than southern hemisphere summer weather (which occurs in January, when the Earth is closest to the Sun).

Mars spends the month in the morning sky, edging closer to the famous Pleiades star cluster and the planet Jupiter. It rises about 2:30 a.m. local time at the beginning of July and by 1:30 a.m. local time by month’s end. Still distant, it appears too small in a telescope for very good views.

Jupiter rises about 3:30 a.m. in the east-southeast, the brightest object in this part of the sky and just above the V-shaped star cluster that marks the face of Taurus the Bull. By month’s end it rises before 2 a.m. and forms a pretty triangle with Mars and the bright star Aldebaran.

Saturn is getting high enough this month for decent telescopic views, but you’ll have to get up early. The ringed planet rises shortly after midnight in early July and by 10:30 p.m. at the end of the month, but it will be at its best telescopic view when at its highest, in the early morning sky a couple of hours before dawn. Saturn’s 29.5-year orbit around the Sun gives us a differing angle to views the amazing rings of Saturn, and this year we see them almost edge-on. While this makes it less impressive than other years, they are still an amazing sight in any telescope. This geometry also opens up a series of events for Saturn’s 146 moons, several of which will transit across the planet’s disk or cast their shadow onto the cloud-tops.