Posted on: Wednesday April 12, 2017

Have you ever seen an uprooted tree while walking in a forest? If so, you might have noticed strands of white thread-like structures attached to the tree roots and running through the soil. What you were seeing were mycorrhizal fungi. These fungi surround and bind almost all of the plants growing in an ecosystem together. Some of them, like the honey fungus (Armillaria mellea; pictured) are even luminous, glowing in the dark. The honey fungus is also the world’s largest organism (that we know of, at least); one specimen stretches for an astounding 2.4 miles (3.8 km) (Ferguson et al. 2003)! This fungus is attached to hundreds of trees, which are also attached to countless other mycorrhizal fungi and forest plants. Sugars, water, and nutrients are exchanged between the plants and the fungi. Trillions of insects and microorganisms live on, and interact with these fungi-root systems. Unfortunately, our understanding of this massive system is horrible, because we can’t actually see what is going on.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

It’s important to remember that the parts of a forest or a prairie that we can see above ground are probably less than a half of the ecosystem’s total biomass; almost all of the fungal biomass is beneath the ground.

Some mycorrhizal fungi appear to only associate with certain plant species while others are less discriminating. About 80% of all plant species (including all trees) associate with mycorrhizae; the plants that don’t are the rushes, sedges, nettles, mustards, goosefoots, and pinks. Some plants are so dependent on mycorrhizae that they can’t live without them: the orchids are one such group. While most mycorrhizal relationships appear to be mutualistic, with both partners benefiting from the interaction, many orchids appear to be parasitic on the fungi!

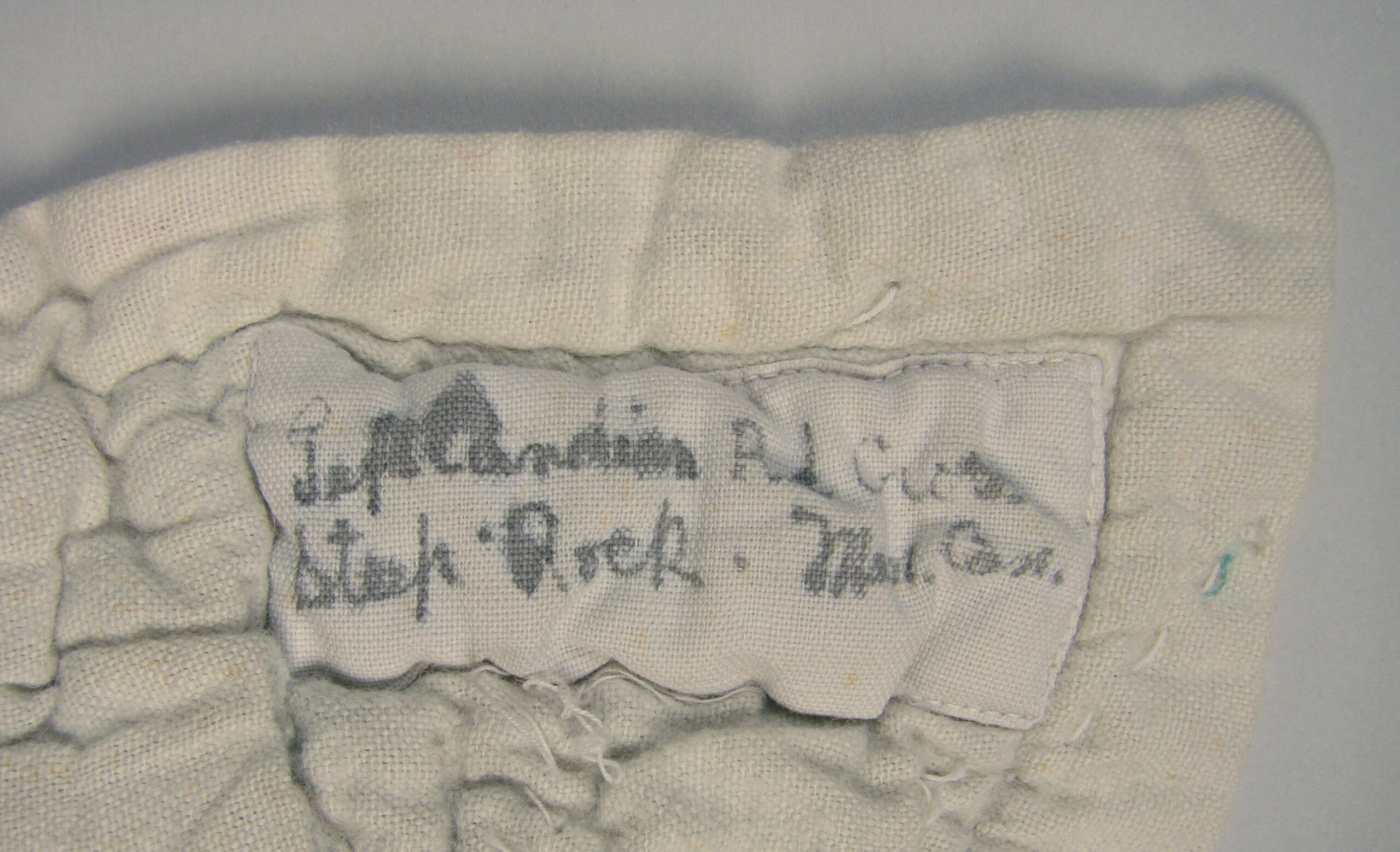

Plants in the mustard family like Western wallflower (Erysimum asperum) are some of the only species that do not associate with mycorrhiza. © MM

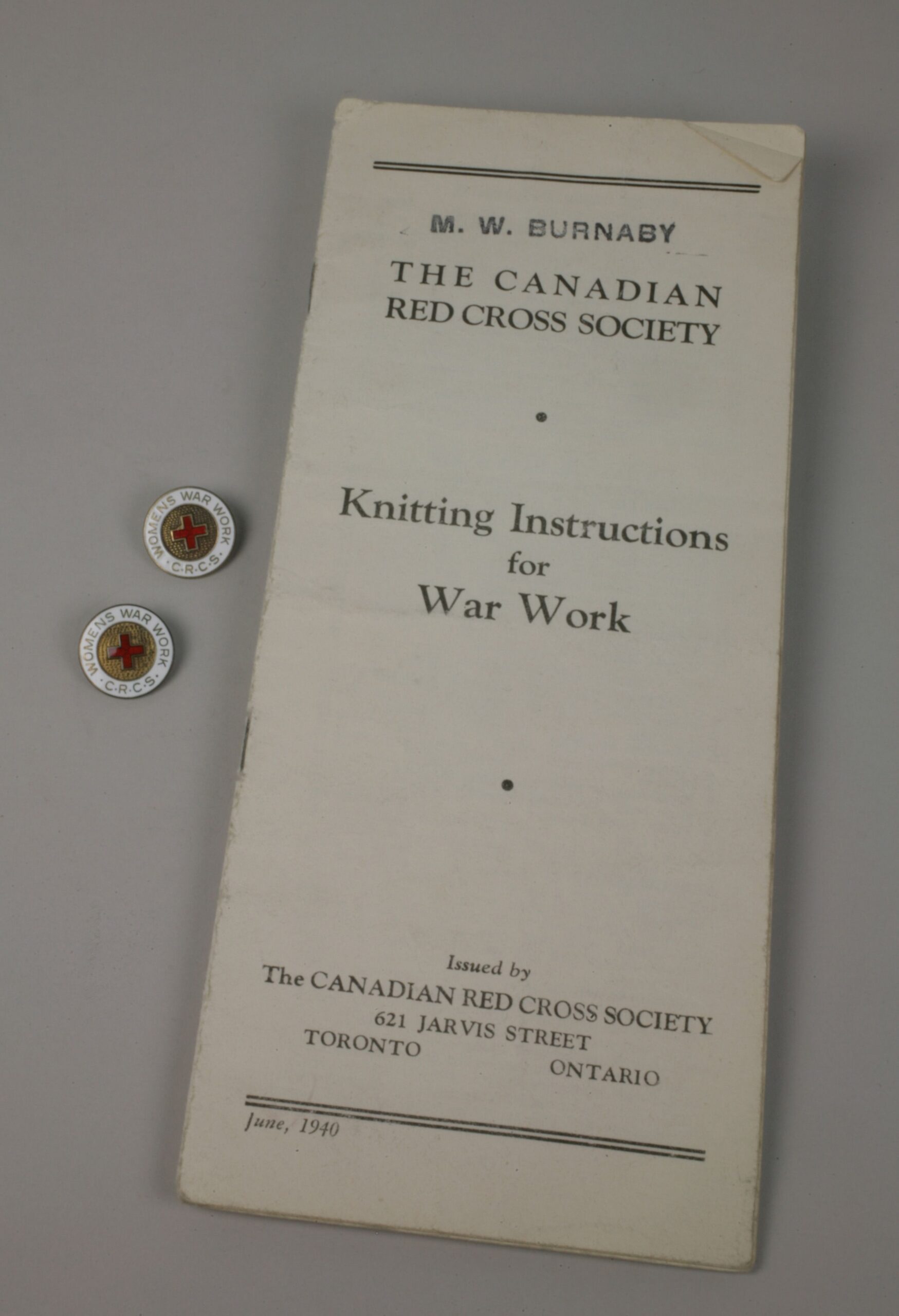

Striped coralroot (Corallorrhiza striata) parasitize both trees and mycorrhizal fungi. © MM

The most parasitic orchids are the coralroots (Corallorrhiza spp.). These species are vascular plants that can no longer photosynthesize, as indicated by the fact that they are orange instead of green. Coralroot orchids parasitize mycorrhizal fungi, which form relationships with pine (Pinus spp.) trees. Thus all of the sugars the coralroot uses to fuel its growth come from the pine trees (via the mycorrhiza), and the water and minerals it needs come from the fungus (Zelmer and Smith 1995).

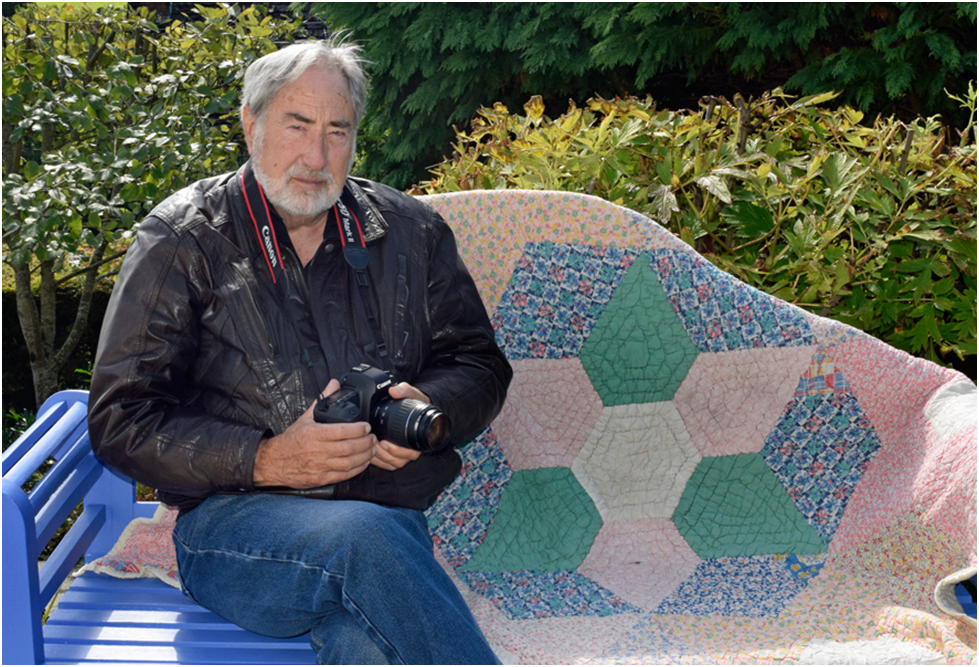

Mycorrhizae appear to help tree “parents” feed their offspring. In “The Hidden Life of Trees” the German forester Peter Wohlleben describes how sugars produced by large, adult trees in a forest are transferred through the mycorrhizae to the saplings, which are unable to access much light. In this way, young trees are provided with enough nourishment to stay alive until the adult tree dies and the young ones can obtain light for themselves. Resources are even transferred between trees of different species. Douglas firs (Pseudotsuga menziesii) were found to transfer nutrients to paper birch (Betula papyrifera) trees in the spring and fall when the birches had no leaves and the birches transferred nutrients to the firs in the summer when their leaves were shaded (Song et al. 2015). Wohllenben thinks that this happens because “a tree can be only as strong as the forest that surrounds it.”

This is just the tiniest shred of what scientists know about mycorrhizae and new studies are being conducted all the time using new tools and analytical techniques. Next time you’re out hiking in a forest remember this amazing invisible world under your feet!

Image: Paper birch (Betula papyrifera) trees exchange nutrients with other trees through mycorrhizal links. © MM

References

Ferguson, B.A., T.A. Dreisbach, C.G. Parks, G.M. Filip, and C.L. Schmitt. 2003. Coarse-scale population structure of pathogenic Armillaria species in a mixed-conifer forest in the Blue Mountains of northeast Oregon. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 33:612-623.

Song Y.Y., S.W. Simard, A. Carroll, W.W. Mohn and R.S. Zeng. 2015. Defoliation of interior Douglas-fir elicits carbon transfer and stress signalling to ponderosa pine neighbors through ectomycorrhizal networks. Scientific Reports, 5 8495. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep08495

Wohlleben, P. 2016. The hidden life of trees: What they feel, how they communicate discoveries from a secret world. Greystone Books.

Zelmer, C.D. and R.S. Currah. 1995. Evidence for a fungal liaison between Corallorrhiza trifida (Orchidaceae) and Pinus contorta (Pinaceae). Canadian Journal of Botany 73:862-866.