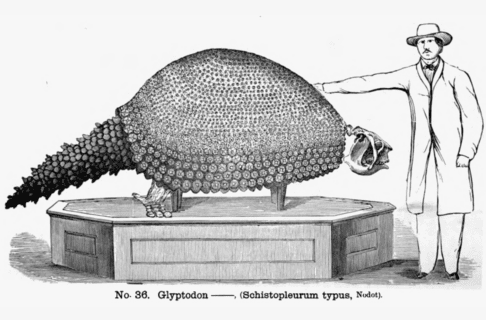

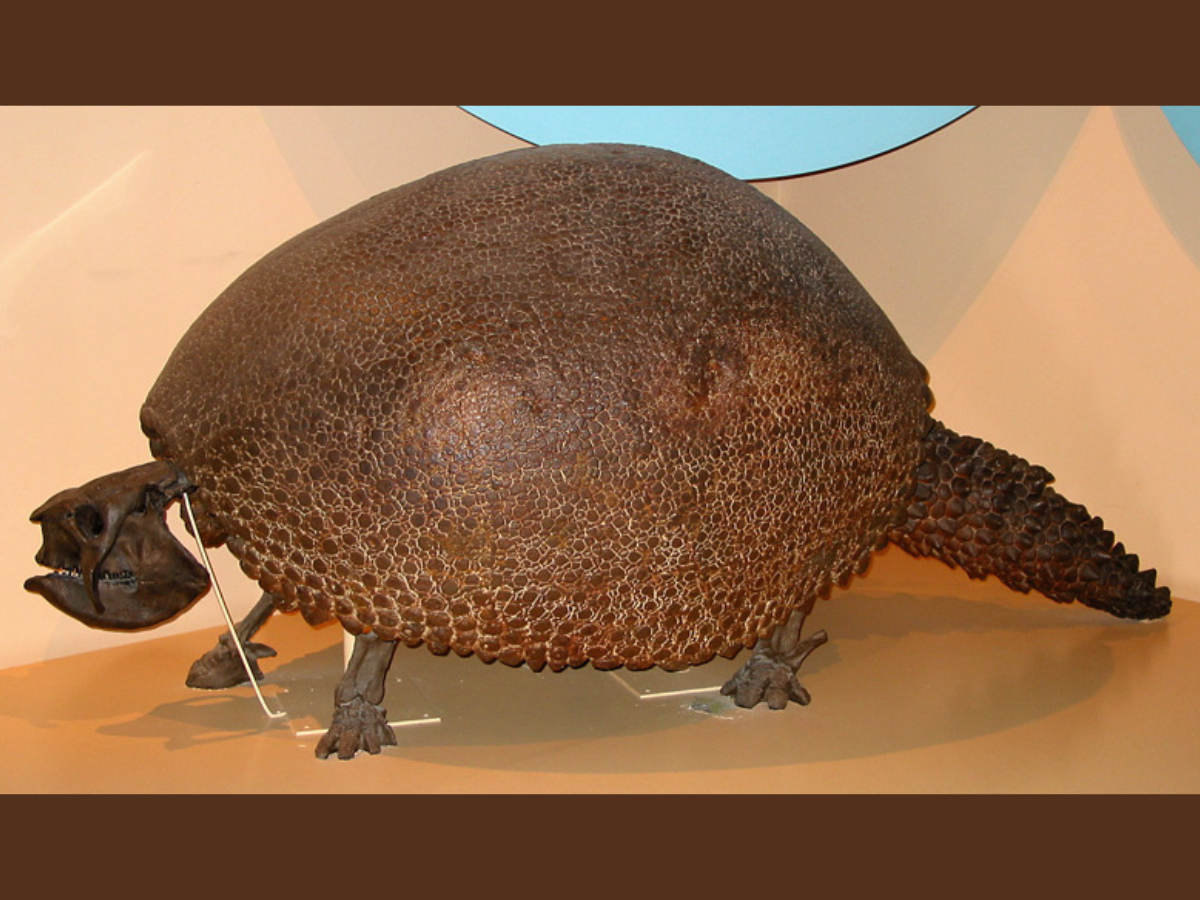

Glyptodonts were creatures that lived during the Ice Age, that have been described as “fridge-size armadillos,” although the largest ones could perhaps have been called “armadillos the size of Volkswagen Bugs.” They were heavy, armoured creatures that weighed up to two tonnes. They spent their time lumbering around the forests and plains of South America and southern North America, eating trees and grasses. Glyptodonts became extinct about 10,000 years ago during the “Quaternary Extinction Event,” at about the same time as giant ground sloths and other large mammals, probably as a result of climate change and hunting by humans.

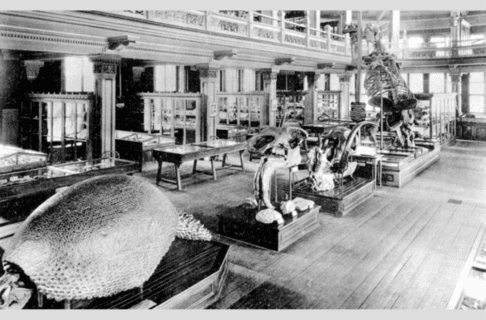

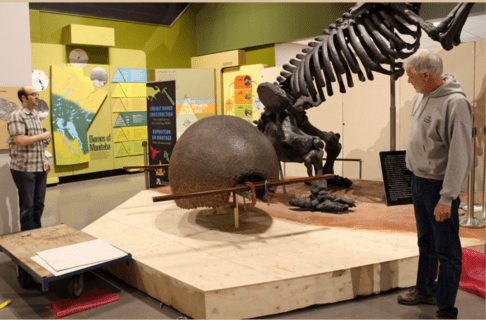

Our particular glyptodont is a replica of a fossil that belonged to the genus Glyptodon, and like our ground sloth it came to the Museum by a long and circuitous route. The glyptodont and the ground sloth were among the earliest casts of big vertebrate fossils, produced during the late 19th century by Ward’s Natural Science Establishment in Rochester, New York. Our ground sloth (Megatherium) was supplied to the Redpath Museum in Montreal in time for the opening of that institution in 1882, while the glyptodont joined it in Montreal some years later.

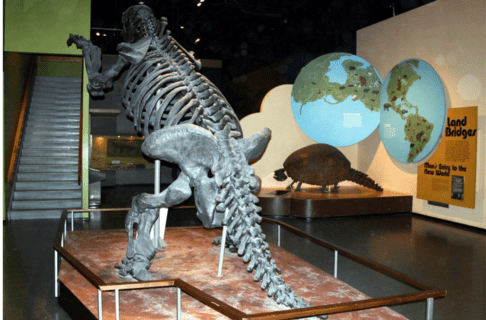

By the 1960s, the Redpath was renovating, and these immense casts were removed and needed a home. The Manitoba Museum was under construction, so the casts were transferred to us and shipped to Winnipeg. They were assembled when the Earth History Gallery was constructed, and were there in time for the gallery opening in 1973. For the forty-plus years since then, both of these huge and historic casts have stood in place on the platforms that had been constructed for them.

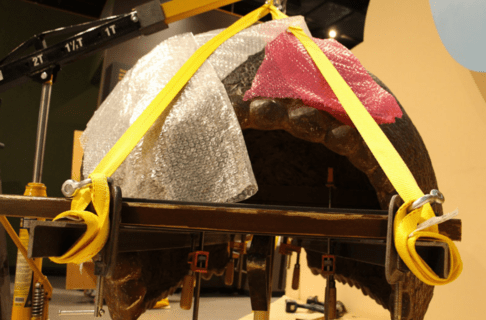

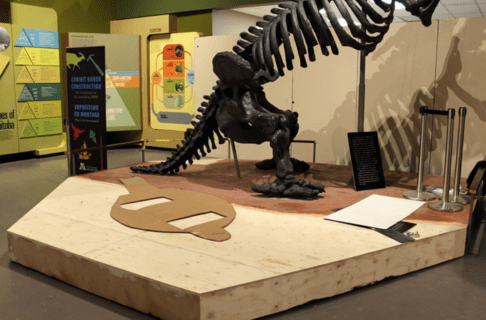

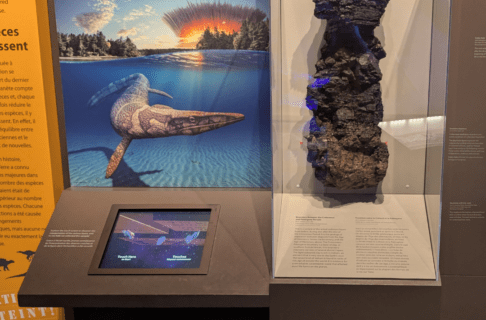

Now, in 2016, we are renovating that part of the gallery so that we can install our exciting fossil pliosaur, and to make space we have had to move the glyptodont. Since this replica had been in place since long before any of us worked here, we did not have any advance knowledge of how it should be handled, and since it is an irreplaceable artefact dating from over a century ago, we considered this move with some trepidation. Since it turned out that the glyptodont is also immensely heavy, having been constructed of plaster, wood, and iron in the best 19th century fashion, our trepidation was well placed.

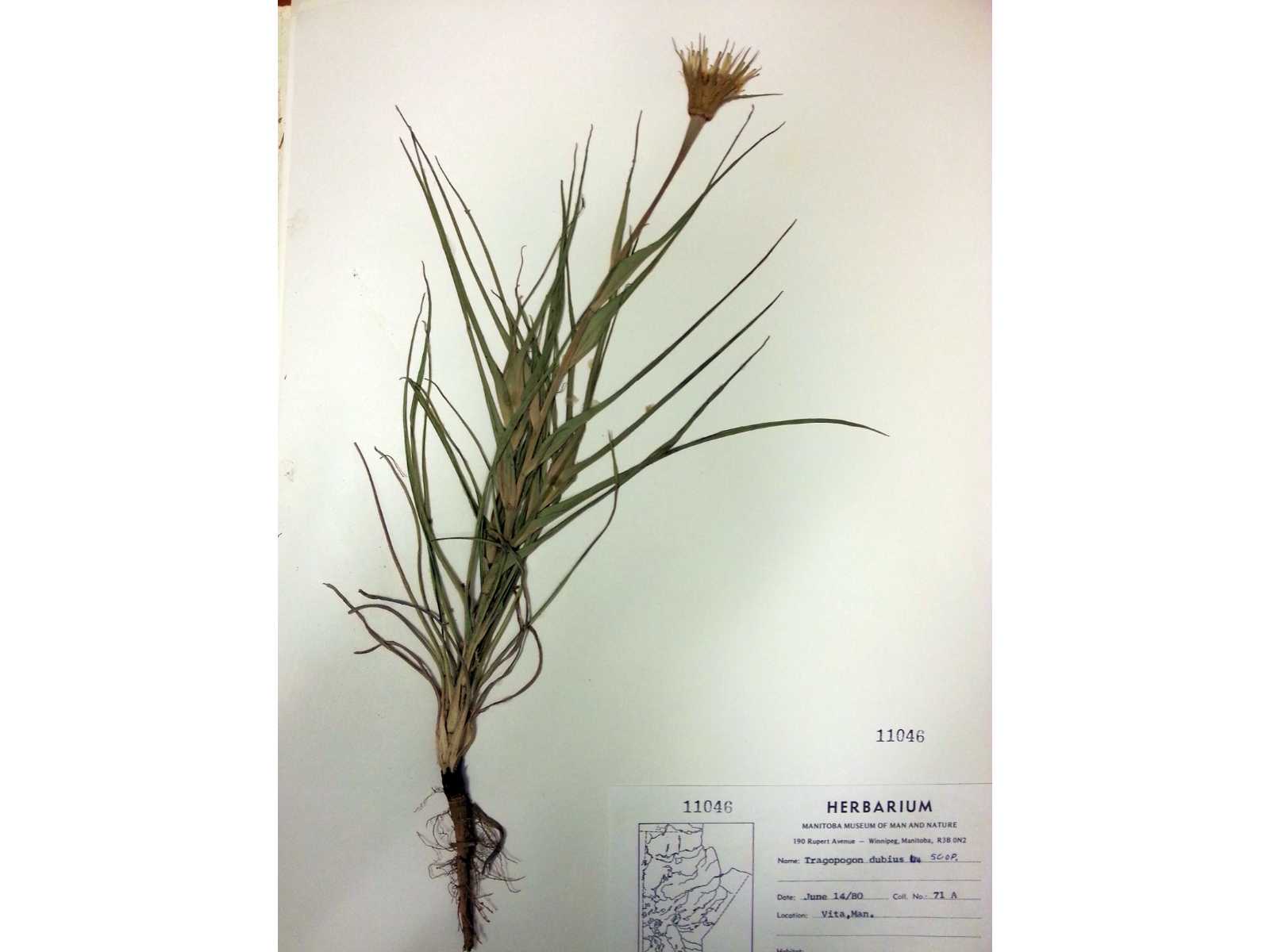

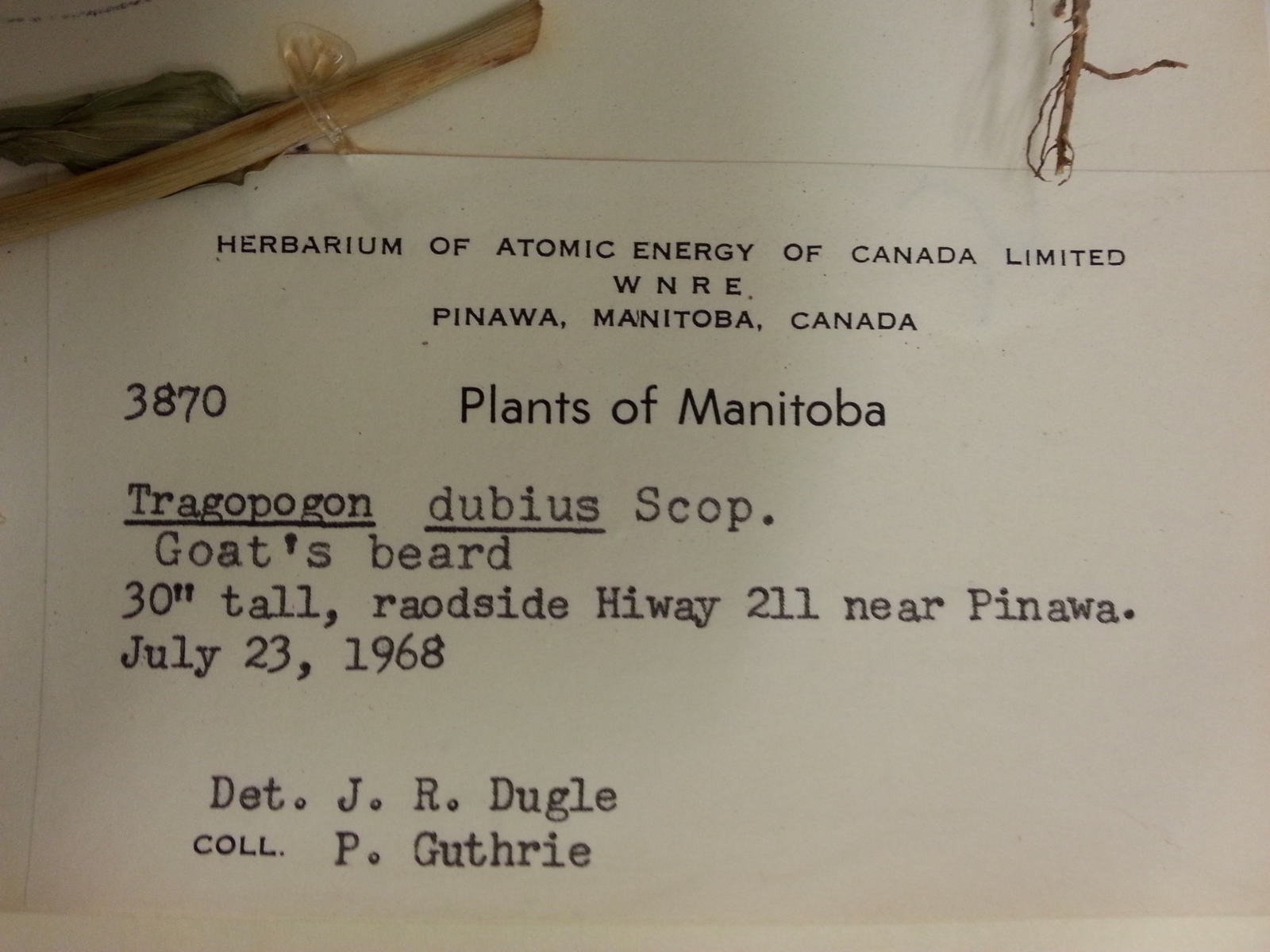

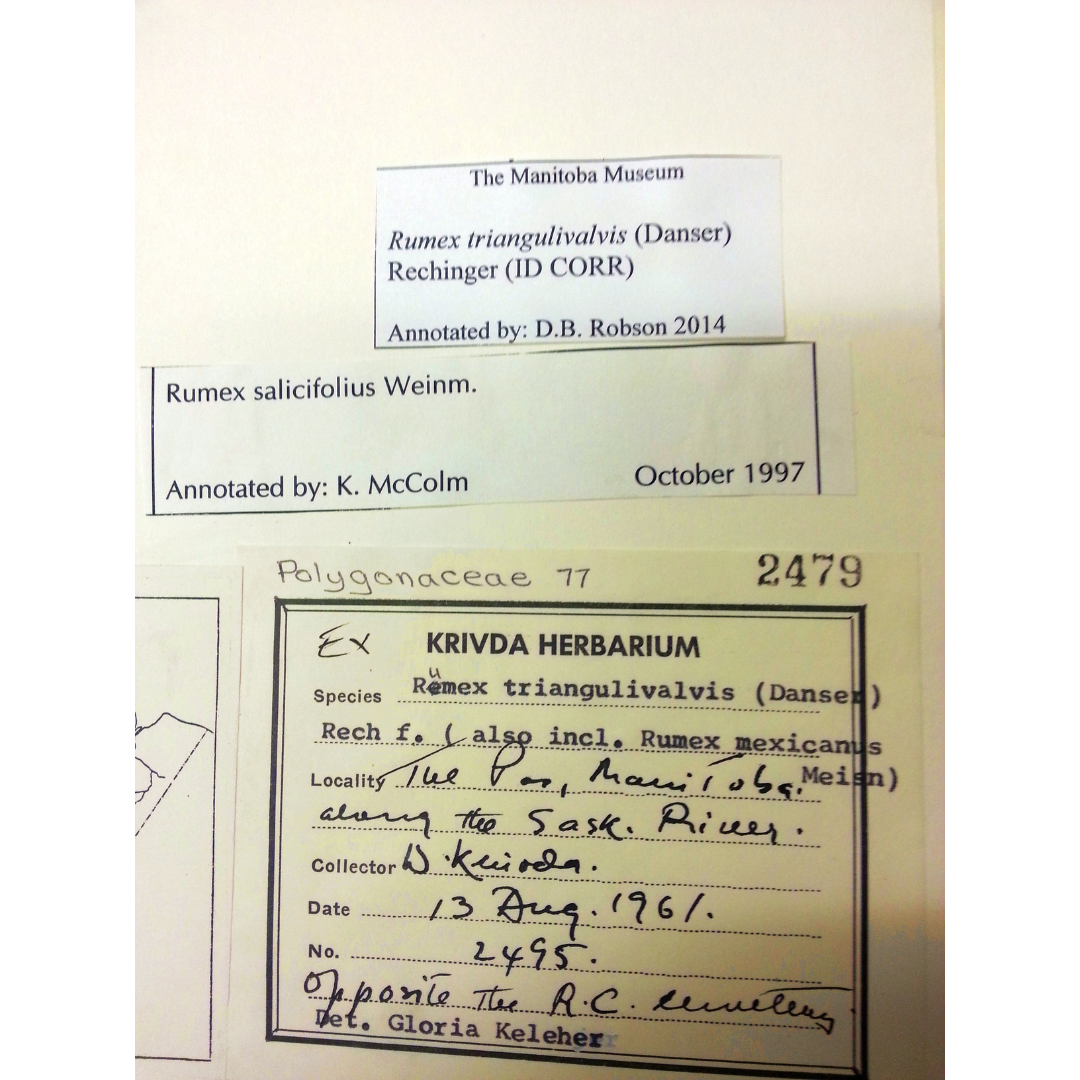

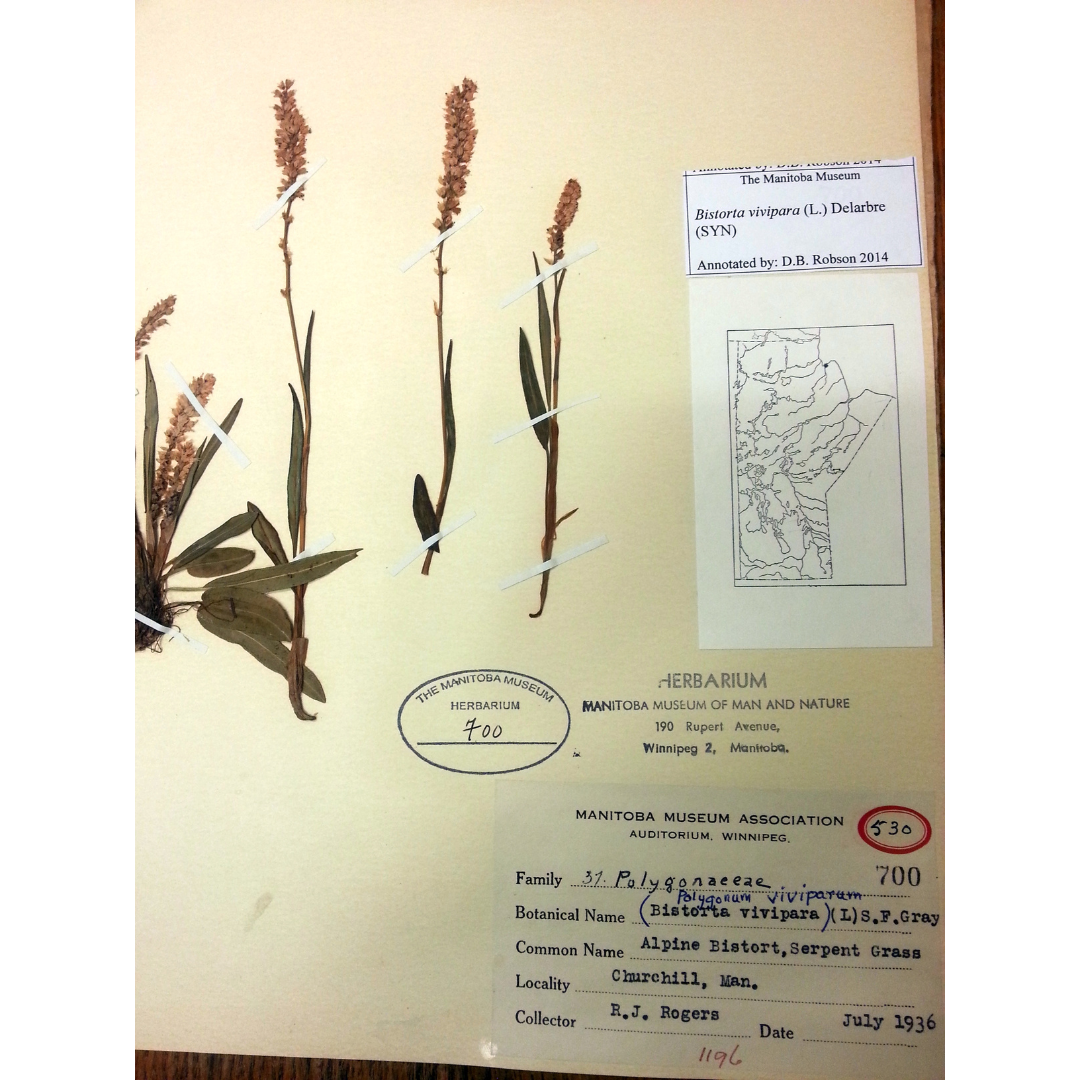

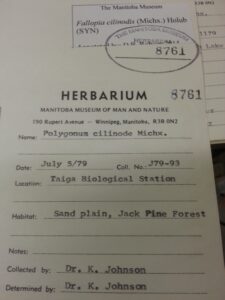

Recently, my husband asked me what I was working on, and when I told him I was updating the nomenclature for specimens in the Family Polygonaceae, he looked at me funny. I realized that as a non-biology person, my response was not that informative to him. It did not tell him that I was working on updating the official names of plant specimens, or even which plants they were, and it also did not make sense as to why their names would even change.

Recently, my husband asked me what I was working on, and when I told him I was updating the nomenclature for specimens in the Family Polygonaceae, he looked at me funny. I realized that as a non-biology person, my response was not that informative to him. It did not tell him that I was working on updating the official names of plant specimens, or even which plants they were, and it also did not make sense as to why their names would even change. When a living organism is recognized as being unique and different from other organisms, it is assigned a scientific name. This is the name that is used in the Museum’s database. A common name may be also included, but common names are not as useful or informative. This is because common names are different in each language. For example, the domestic dog is “perro” in Spanish, “chien” in French, “sobaka” in Russian, “gŏu” in Mandarin, “hund” in Danish, and “cane” in Italian. However, the scientific name for dog is Canis familiaris, and this is the same everywhere in the world.

When a living organism is recognized as being unique and different from other organisms, it is assigned a scientific name. This is the name that is used in the Museum’s database. A common name may be also included, but common names are not as useful or informative. This is because common names are different in each language. For example, the domestic dog is “perro” in Spanish, “chien” in French, “sobaka” in Russian, “gŏu” in Mandarin, “hund” in Danish, and “cane” in Italian. However, the scientific name for dog is Canis familiaris, and this is the same everywhere in the world.