Posted on: Thursday December 15, 2011

The Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI) is part of the federal Department of Canadian Heritage, created to promote the preservation of Canada’s cultural heritage. Every two to three years, CCI develops and hosts in Ottawa a symposium on a conservation topic.

For a week in October conservator Lisa May attended Symposium 2011 – Adhesives and Consolidants for Conservation: Research and Applications.

Internationally attended, the symposium covered the newest research, techniques and products for a wide range of adhesives and consolidants used in conservation. Papers and posters addressed use of these products on virtually every type of material that conservators encounter.

A dedicated poster session and generous breaks allowed for opportunity to speak to the presenters as well as mingle with the over 200 participants. In addition, one afternoon was dedicated to tours of Ottawa institutions.

The last day of the symposium was at CCI where the paper authors, as well as other conservators and scientists working at CCI, demonstrated their new research, techniques, and applications. There were over 30 participants presenting 25 minute demonstrations, with each offered four to five times during the day to accommodate all those in attendance. -Lisa May

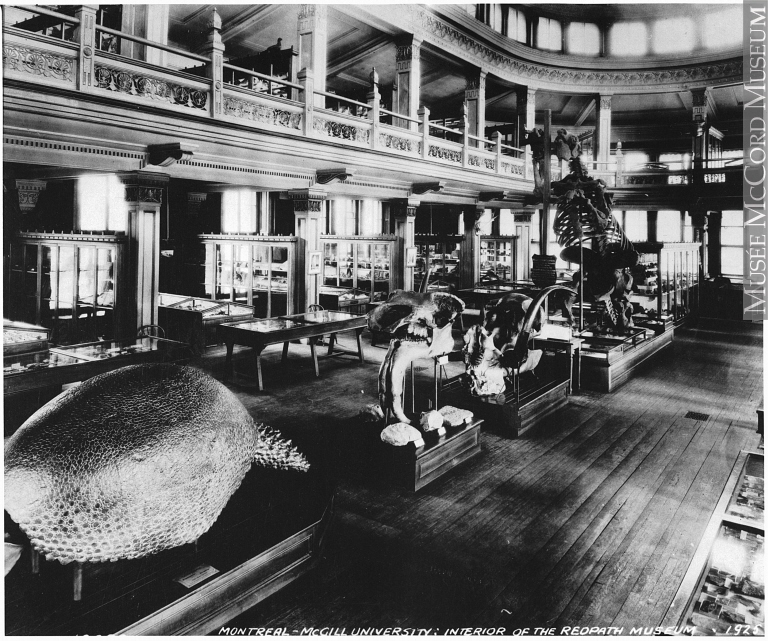

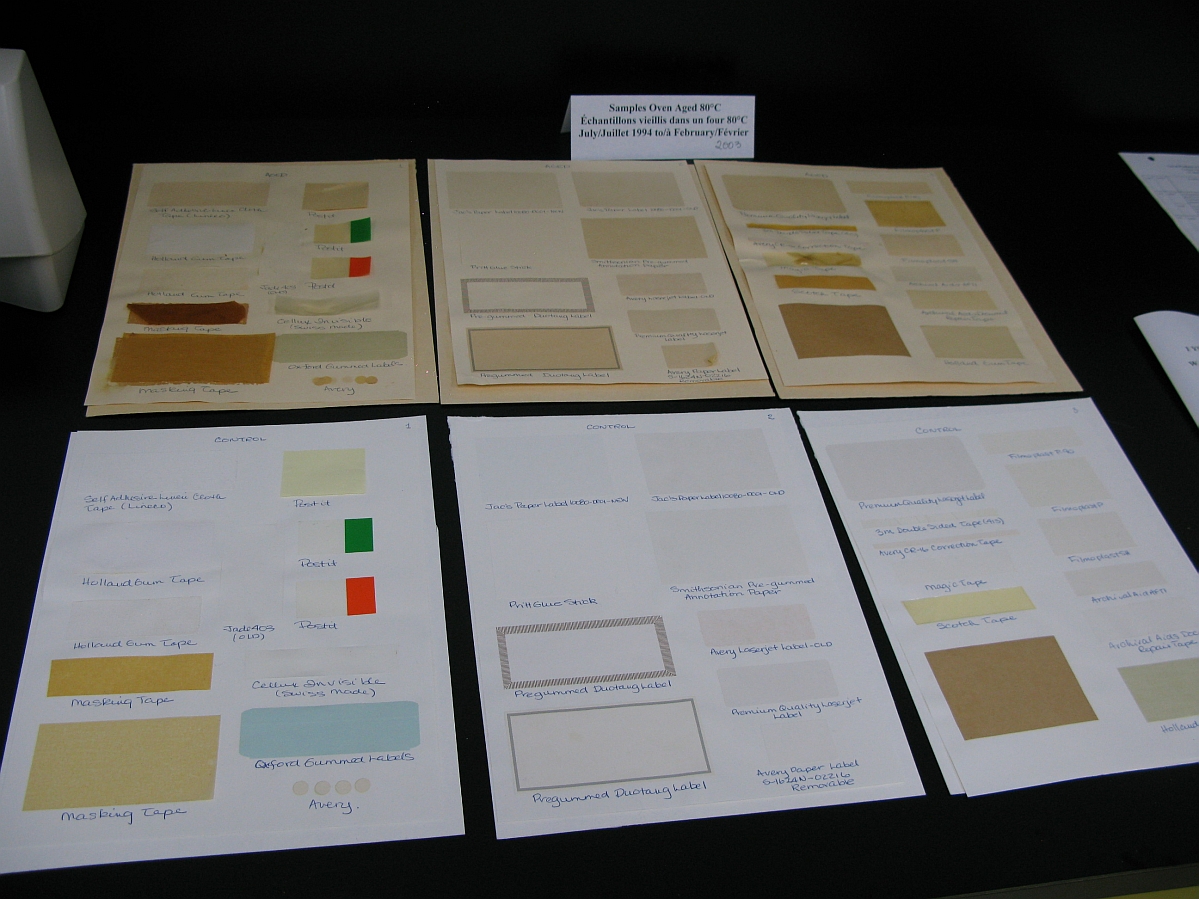

The opportunity to attend this symposium has allowed for Lisa to return with new contacts and up-to-date information we will use in conservation treatments. In particular, there are some Natural History specimens awaiting our attention, about which she gleaned pertinent suggestions on materials and techniques. Below are three photos Lisa took during the demonstration day.

Original and oven aged self-adhesive tapes and labels samples.

Repairing a parchment tear with gelatine and goldbeater’s skin.

Parylene coated newspapers and leaves.