Posted on: Thursday April 23, 2020

Amongst the many and varied Natural History Collections at the Manitoba Museum, is a most unusual collection of ‘cases’. These unique display cases of glass panels held together by dark varnished wood frames, are commonly known as parlour cases. The contents combine the artistry of fabricating faux habitats, with the expertise of creating life-like mounts through taxidermy. Some are as small as to only contain a single mounted Least Weasel, others are several feet tall, and may contain dozens of birds and mammals.

Parlour cases became highly popularized during the Victorian era, from about the early to mid 1800s into the early 1900s. This was a heightened time in the discovery of the natural world, and also coincided with, and was stimulated by, the great scientific exploration voyages of Darwin, and his contemporaries. Parlour cases were born out of this time of fascination and the desire to collect and display specimens.

It was commonplace to display these cases in the reception parlours of well-to-do households, thus the name. Owning and displaying these in your private collection reflected on their owners as having attained a certain level of good taste, intellect, and an aire of affluence; “parlour cred” if you will.

A true menagerie – this beautiful example of a traditional parlour case was donated to the Museum in 1973. Image: © Manitoba Museum, MM 3-6-501 to 3-6-532

However, displaying taxidermy mounts was a practice not only reserved for the rich. They were also displayed in schools for educational purposes, and in the houses of commoners, possibly to demonstrate hunting prowess, or as an attempt to be perceived as affluent.

This very simply prepared case of Woodcocks was possibly a grade school project – see label “Presented by Dudley Fraser”, date unknown. Image: © Manitoba Museum, MM 3-6-5578, 5579

Early taxidermists were indeed artists and masters of many trades. Expert taxidermists of the time would have been in demand and could command high prices for commissioned work. Not only would they need to know the techniques involved to properly preserve the skin, but they must also have knowledge of anatomy, and aspects of animal behavior. It is extremely difficult to obtain the exact correct posture, or facial expression to match the particular theme of the case, whether it be animals at ease, or reconstructing a predator-prey scenario.

Excellent taxidermy of a Blue Jay that mimics John J. Audubon’s artistic vision. Image: © Manitoba Museum, MM 3-6-476

Plate 102, from John James Audubon’s Birds of America (1827-1838). Image: National Audubon Society

Knowledge of ecosystems must also be appreciated. For example, which animals and plants would actually be found together in the same habitat, or even in the same season. This knowledge and skill executed in taxidermy scenes, and even the large dioramas in our museum, makes for a highly believable portrayal.

However, some of parlour cases ignored that concept of realism out-right and had mounts of birds and/or mammals that would never have seen each other in a given day, or even in a lifetime.

Expertly prepared life mount of an Elk. This diorama in the Museum’s Parklands Gallery depicts rutting season in Riding Mountain National Park. Image: © Manitoba Museum

Goshawk with Vesper Sparrow prey is an example of two species that might not encounter each other in a North American winter. Image: © Manitoba Museum, MM 3-6-534, 536

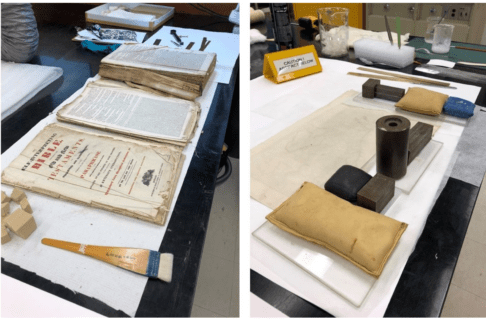

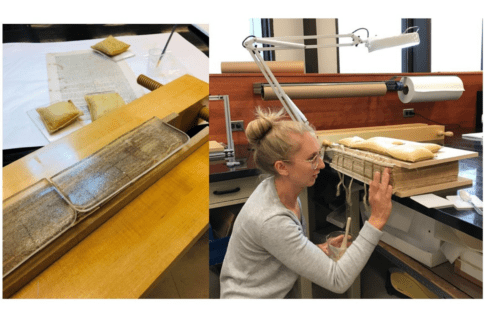

Recently, we had to move our entire collection of large parlour cases from where they were stored in our main collections storage vault. Long tracks of ducting were being installed for the new environmental control unit, and we wanted these far from any danger. We took advantage of this move to inspect, photograph, clean, repair (if necessary), and ensure the database information was complete for each one of these large, fragile cases. The taxidermy specimens, faux substrate, glass panels, and the wood framing were expertly cleaned and repaired by the Museum’s conservator Carolyn Sirett.

Before conservation treatment photograph on the left shows the old masking tape “holding” the glass panel in place, and the after conservation treatment photograph on the right shows a much improved parlour case that has been cleaned and repaired. Image: © Manitoba Museum, Parlour Case #3

During conservation treatment, the cases were also tested for the presence of arsenic. We were not surprised to find that many of the specimens tested positive. Now that specimens have been identified, we take extra precautions when we have to handle them, such as wearing gloves and masks.

Arsenic was a common and favoured compound used by taxidermists from the late 1700s to at least the 1980s. Eventually its use was banned due to its high toxicity to humans. It was prepared as an arsenical soap, and applied to the inside of prepared skins that not only preserved the skin, but also provided protection of the mount from insect damage. This is the reason why so many of the old taxidermy mounts have survived in such splendid condition!

GUILTY! Ermine mount tested positive for arsenic! Image: © Manitoba Museum, MM 24116