Posted on: Wednesday June 28, 2017

Post by Karen Sereda, past Collections Registration Associate (Natural History)

Where do all the dead animals come from?

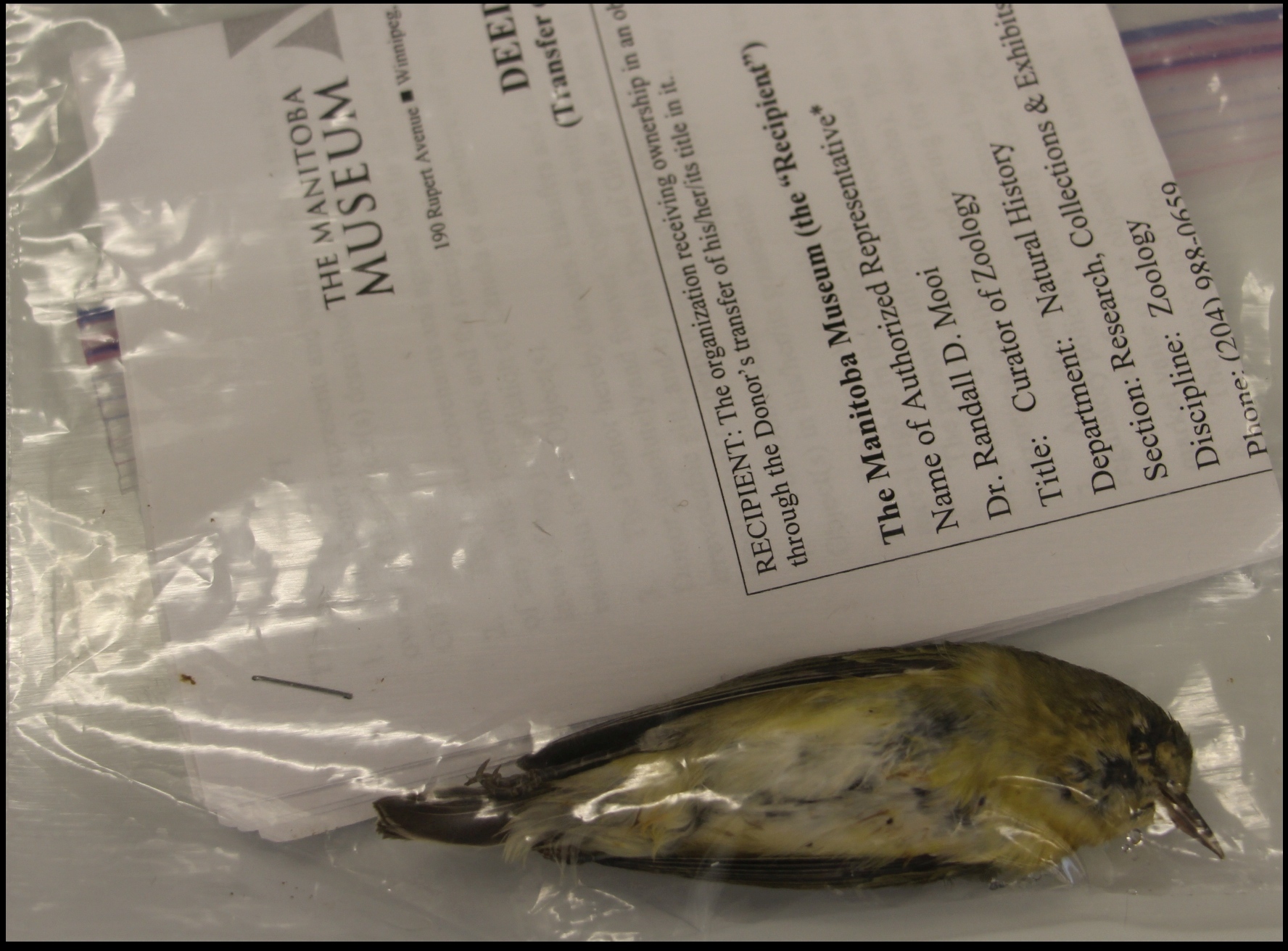

This is a common question we get at the Museum. People sometimes think that Museum staff regularly go out and kill birds and other animals for displays. This is not the case. Birds for example, sometimes accidentally fly into windows and die. We call these “window strikes”. If someone noticed at the time, they may go and pick the dead bird up, put it in a bag and freeze it. At a later date, that person might bring the bird to the Museum. If the Curator of Zoology, Dr. Randy Mooi, accepts the bird as a donation, then it is thawed and a bird skin is made.

The Museum’s Diorama and Collections Technician prepares bird skins from the donated “window strikes”. You can read more about the preparation of bird skins in this blog by Debbie Thompson.

Image: Frozen bird in a bag, pre-acquisition 1018. © Manitoba Museum

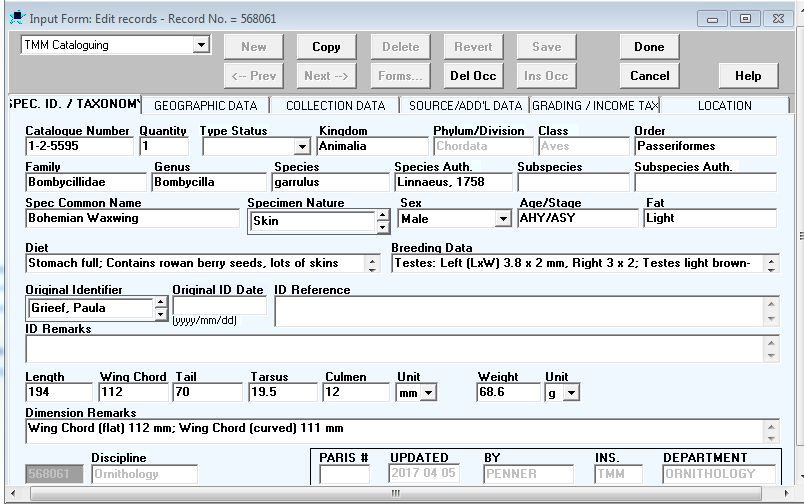

Once the bird skin is dry, the pins can be removed and the specimen is catalogued. The information or as we call it, “the data”, associated with a specimen is just as important to us as the bird itself. When I get a bird skin to catalogue the first thing I usually do is find the donor form, and then look up its name. Dr. Mooi would have already determined its scientific name. The bird is assigned a catalogue number, and its taxonomic classification is confirmed.

Pinned skin of a Scolopax minor (American Woodcock), pre-acquisition 1573. © Manitoba Museum

Skin of a Scolopax minor (American Woodcock) ready for cataloguing, pre-acquisition 1573. © Manitoba Museum

Where, when, and by whom the bird was collected is important information to know. Sometimes the person collecting the bird may have noted the time of day or what the bird was eating, or other interesting information about that particular bird. Donor information is also recorded. All this information makes up the data that is then entered into our digital database.

Image: Screenshot from database of catalogue number 1-2-5595. © Manitoba Museum

So why do we collect bird skins?

Collecting birds, or any other natural history specimen, is a record of where and when a particular organism lived. Bird distributions are known to change. Having a particular bird specimen is physical evidence of a bird living in a particular area. This is sometimes a record of how birds have expanded into new areas, or may have become less common in other areas.

Image: Catalogued Bombycilla garrulus (Bohemian Waxwing), catalogue number 1-2-5583. © Manitoba Museum

Also, not all birds of one species will look exactly the same. Even though they might be of a similar age and sex, birds can be different sizes, and exhibit different colour variations.

Sometimes samples are taken to test for DNA or other chemicals. This is how it was discovered that use of the pesticide DDT was causing the decline of certain species of predatory birds, such as eagles. The decline was because DDT accumulated in the parent birds, and caused thinning of bird egg shells. Then less baby birds would hatch successfully.

So, we never know, someday in the future those birds we collect might serve an unexpected purpose.

Skins of Falco columbarius (Merlin) in the Museum’s collection. © Manitoba Museum