Posted on: Wednesday March 23, 2016

Usually geese migrate from North to South and back again. Some goose decoys, however, migrated from Manitoba to British Columbia a hundred years ago, and have now come home to Manitoba again.

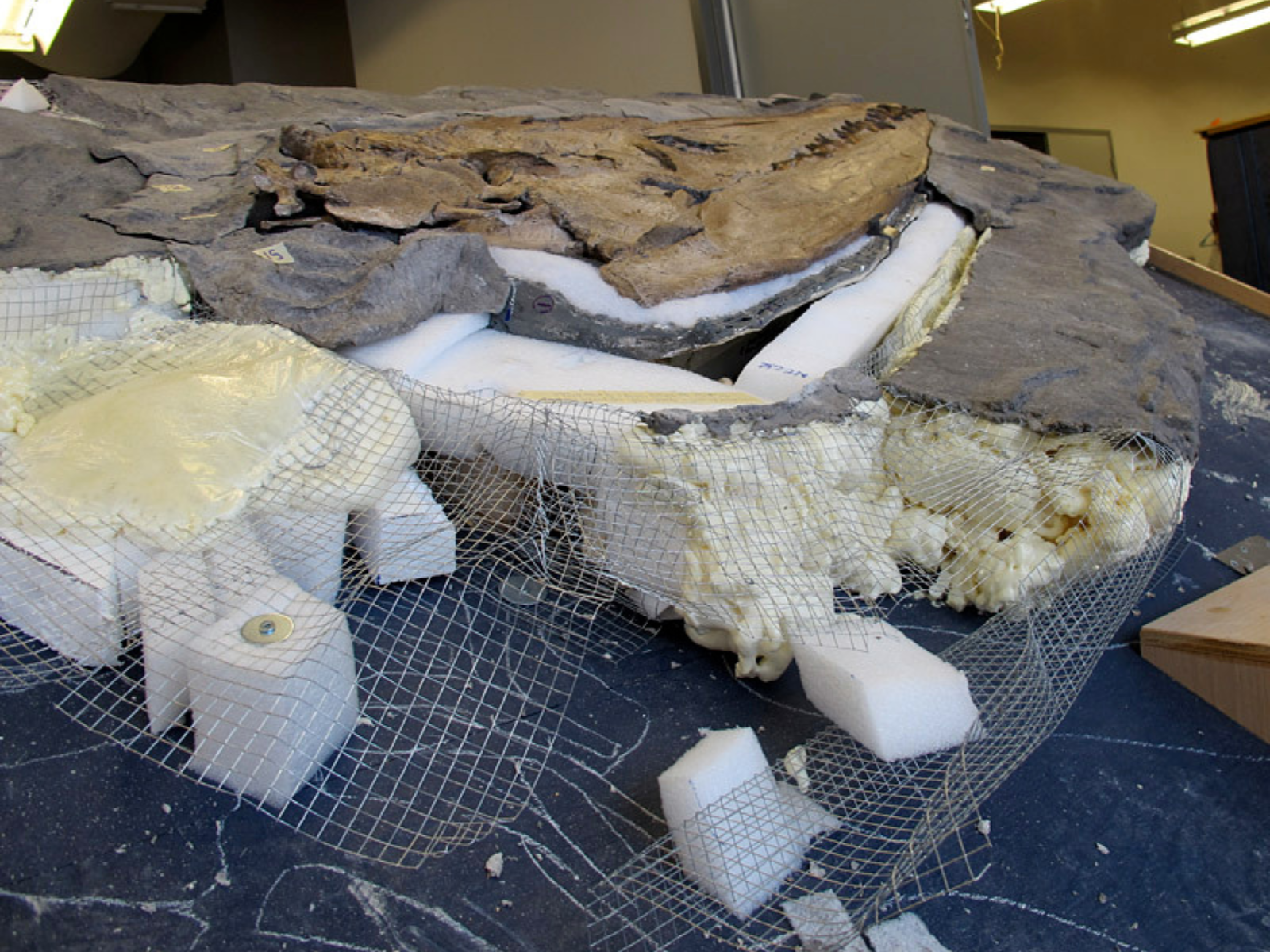

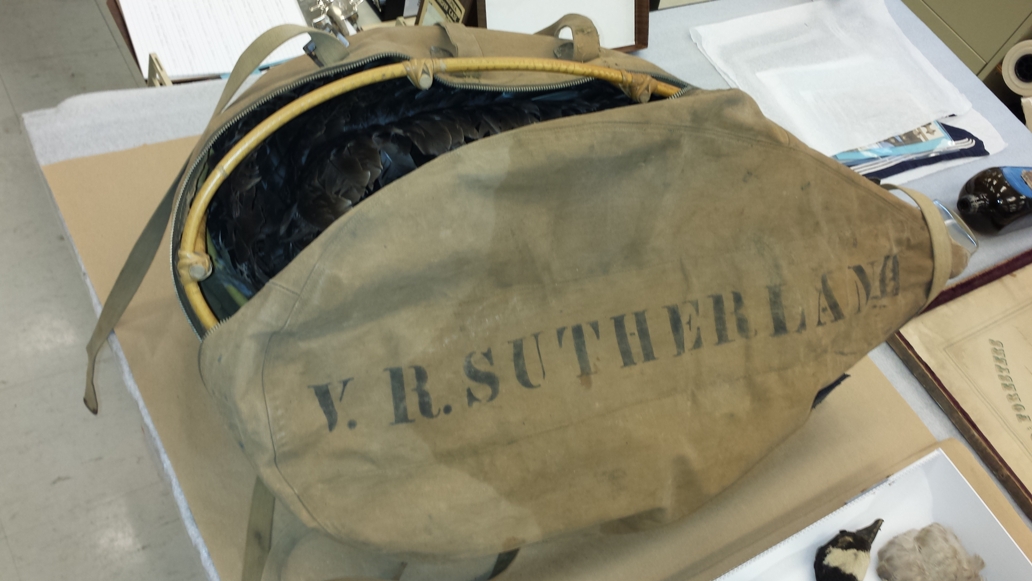

A woman from Victoria, British Columbia called some time ago wanting to donate a batch of goose decoys that had been in the possession of her father. Duck and goose decoys used for hunting are common enough items, but the photographs the donor showed me were unique. These decoys, which were said to have been made in Manitoba in the 1880s, were made from actual geese. Twelve body forms were adorned with goose feathers, and these were accompanied by twelve taxidermied heads. Twelve wooden stakes were also included, and these acted as both stands for the body forms and stakes for the heads. All of these materials were packed neatly in a woven cane structure surrounded by a custom made canvas bag. Printed on the bottom of the bag in large letters: “V. R. SUTHERLAND”.

Image: A goose decoy fully reconstructed. H9-38-380. Copyright The Manitoba Museum.

Preserved goose heads, neatly arranged. The stakes are in the top right hand corner. H9-38-380. © Manitoba Museum.

Underside of decoy body frame. H9-38-380. © Manitoba Museum.

The more closely I looked at the items with my colleagues Dr. Randy Mooi (Curator of Zoology) and Dr. Diana Bizecki Robson (Curator of Botany), the more we learned. Six of the goose heads were Canada Geese, while six were White-Fronted, the latter species being common in western Manitoba. All the heads seem to have been treated with arsenic and some included glass eyes, both common taxidermy methods in the 1880s. The cane frame was made with common cattail. The bag itself is a thick canvas, with a zipper that is of 1930s or 1940s vintage. From this physical examination we can surmise that although the goose decoys themselves may date to 1880s Manitoba, the bag and cane frame probably date to about the 1940s.

So who was V.R. Sutherland? Victor Richard Sutherland (1893-1969) was born in Winnipeg to Roderick Ross Sutherland and Martha Anna Richardson. Roderick was a lawyer and the couple belonged to the upper class of Winnipeg at the time. If the decoys were indeed made in the 1880s they likely belonged to Roderick, and certainly not Victor (who wasn’t born until 1893). The Sutherland family moved to Victoria, BC in 1912, which means the bag and cane frame were likely made there. Victor was a great friend of the donor’s father, G. Fitzpatrick Dunn, and it is believed Dunn received the decoys either from Victor or his wife Lucy in the 1960s or early 1970s.

Image: The canvas bag containing a cattail frame, with enough room for all the components of all twelve decoys. H9-38-380. © Manitoba Museum.

Despite all of this rich historical background and physical examination by experts, we are still not entirely certain where these decoys were made or how old they are. Our best guess is built on stories married with facts. G. Fitzpatrick Dunn’s claim that the decoys were made in Manitoba in the 1880s is given weight because he was a good friend of the man who owned them and who would have provided this information. Another issue is that Canada Geese and White-fronted Geese are found throughout the western provinces, including the Pacific Coast region, so they could have been made in either of the places where the Sutherlands lived.

This is how curatorial investigation sometimes works – a lot of study, revision, and discussion, followed by a plausible but not quite definite explanation. Whatever the case, no one with whom we’ve spoken has ever seen goose decoys like these before. They are unique and look like they were custom made for an avid hunter with financial means. Contact us if you’ve ever seen anything resembling this!