Posted on: Friday September 30, 2011

The Manitoba Museum is home to over 2.6 million artifacts and specimens. One role of the Collections and Conservation staff is to maintain records for each item from the time it is offered to the museum, accepted into the collection and then accessed for research and exhibits or loaned to other institutions. While the numbers may be smaller, the same Collections Management practices are used in community museums throughout the province.

Recently, Nancy Anderson, Collections Assistant-Human History, instructed a training course on Collections Management in Shilo, MB. The aim of the course is to give participants the tools to properly manage a museum collection. The course is part of the Association of Manitoba Museum’s Certificate Program in Museum Practice. The thirteen participants represented ten museums throughout the province, including three new museums in Argyle, Brandon, and Richer.

Participants take on the role of a Collecting Committee at a fictional museum and debate whether a list of objects fits the museum’s Collections Policy.

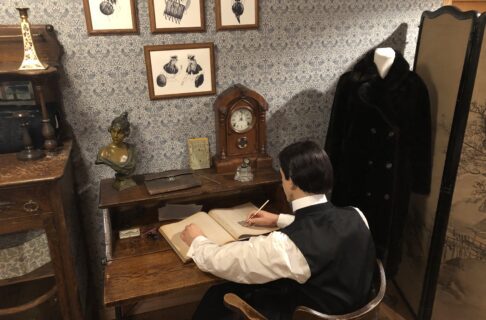

Following the path of a new artifact through a collections procedures flow chart.

In order to be good stewards of our heritage, museums need to be selective in what they accept into their collection. Participants frequently want to know how to fairly represent the various families, businesses, and organizations within their community without alienating community supporters or overwhelming the museum’s volunteers and resources. In other words, how do you say no? The answer to that question is to develop a Collections Policy that lets people know what you do collect. A strong policy builds on the museum’s Statement of Purpose (why do we exist?) and describes how and what the museum will collect and how the collection will be used.

Sometimes it seems like the motto for Collections Management could be “Paperwork is my life”. The course stressed the importance of establishing procedures for record keeping for museum collections. Good records insure the museums are meeting their legal and professional responsibilities. The accumulated information about an item enhances its value. Proper catalogue records link that item with its story so that the knowledge can be shared with others.