Posted on: Wednesday October 24, 2018

Image above: In late autumn, the search for fossils in the Grand Rapids Uplands can be cold yet rewarding. Dave Rudkin of the Royal Ontario Museum visits a collecting site on a cold October morning.

Blog by Dr. Graham Young, past Curator of Palaeontology & Geology

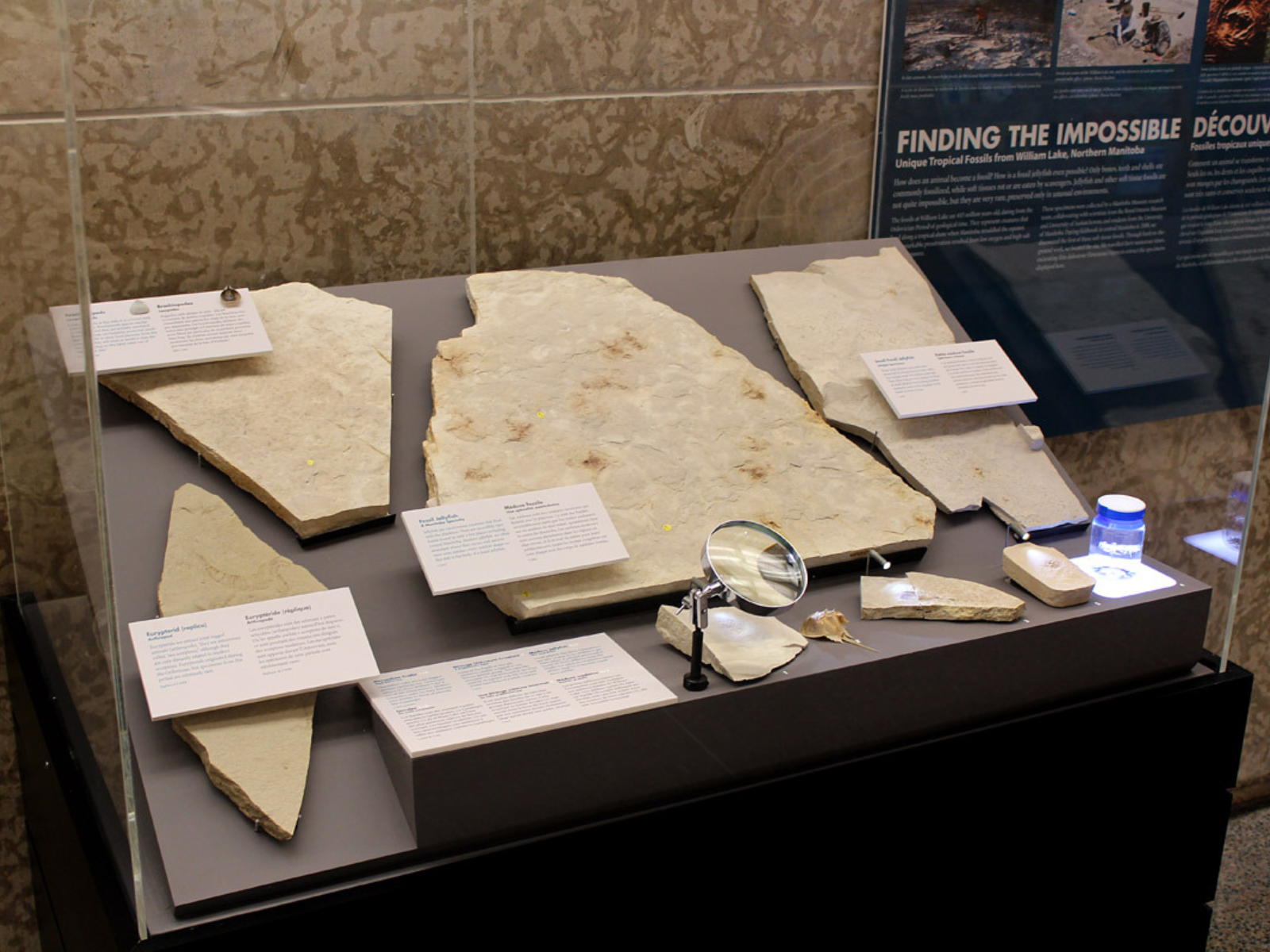

This year, our Museum foyer has featured an exhibit of unusual fossils in the New Acquisitions Case. This exhibit, Finding the Impossible: Unique Tropical Fossils from William Lake, Manitoba, included a video “slide show” that documented the expeditions during which we collected these fossils. My colleague remarked to me the other day that this slide show should be shared widely using the Museum blog; this post, and some subsequent ones, will do just that!

The exhibit panel’s text gives a brief outline of the project:

How does an animal become a fossil? How is a fossil jellyfish even possible? Only bones, teeth and shells are commonly fossilized, while soft tissues rot or are eaten by scavengers. Jellyfish and other soft tissue fossils are not quite impossible, but they are very rare, preserved only in unusual environments.

The fossils at William Lake are 445 million years old, dating from the Ordovician Period of geological time. They represent creatures that lived along a tropical shore when Manitoba straddled the equator. The remarkable preservation resulted from low oxygen and high salt levels in lagoons.

These specimens were collected by a Manitoba Museum research team, collaborating with scientists from the Royal Ontario Museum and University of Saskatchewan, and students from the University of Manitoba. During fieldwork in central Manitoba in 2000, we discovered the first of these soft-tissue fossils. Through hard on-the-ground work, we located the site. We travelled there numerous times, excavating thin dolostone (limestone) layers to extract the specimens displayed here.

The first part of the accompanying slide show provided some background on Manitoba limestones, and shared the experience of travel to the Grand Rapids Uplands of northern Manitoba. I hope you will enjoy these images.

Manitoba is famous for its Ordovician-age limestones (shown here in the Manitoba Legislative Building) …

… such as the fossil-rich Tyndall Stone. The fossil on the right is the receptaculitid Fisherites. This is a member of an extinct group of organisms; it is commonly called a “sunflower coral”, but was most likely a green alga (“seaweed”).

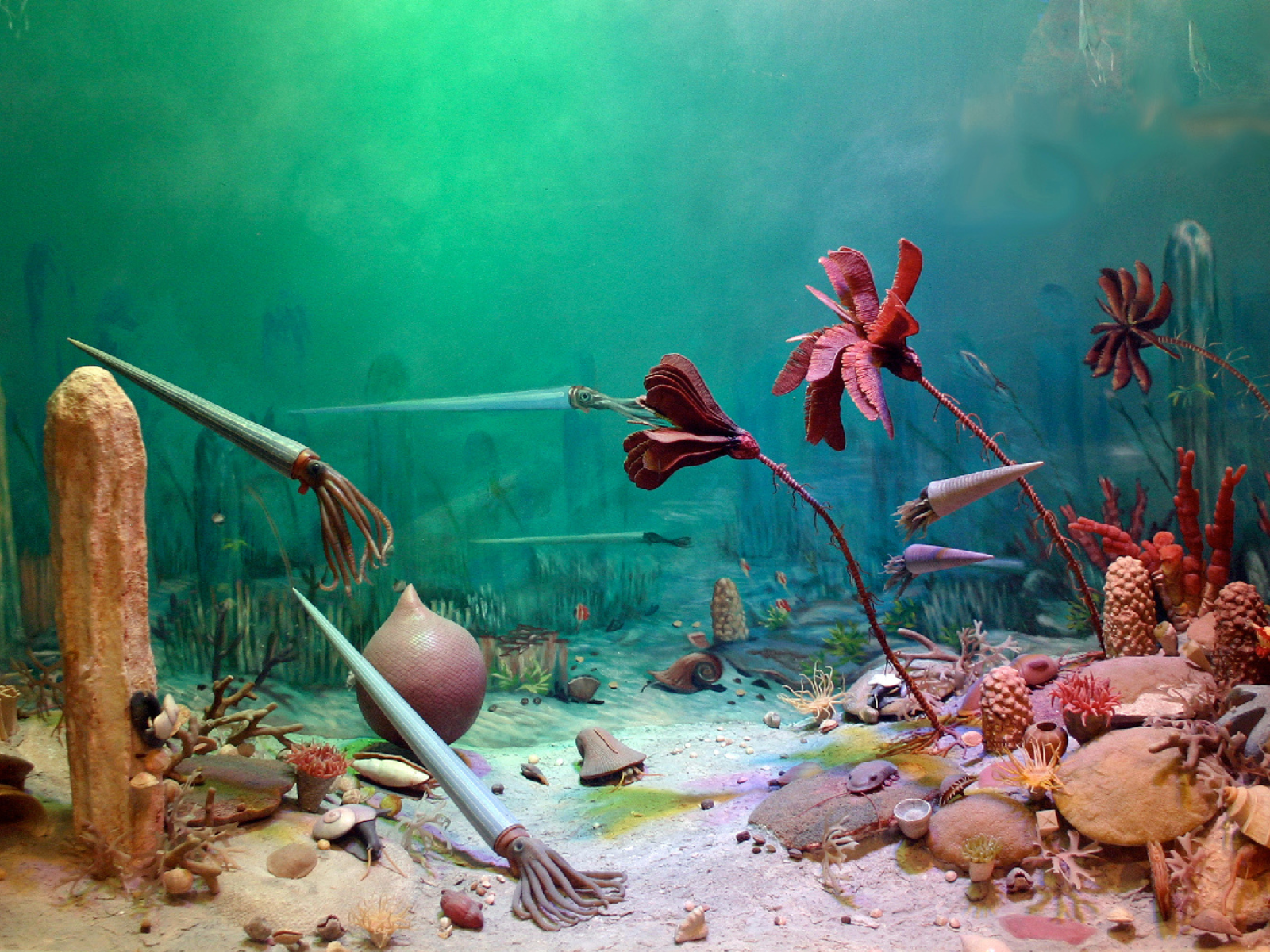

These limestones formed on a tropical seafloor about 450 million years ago (this is the Ordovician seafloor diorama in our Earth History Gallery).

To go from this seafloor to the shore (photo: Graham Young) …

… we must pack our gear (photo: David Rudkin) …

… and travel north (photo: Michael Cuggy) …

… to the Grand Rapids area.

Morning weather can be varied …

… as we get on the road, northward again …

… toward William Lake, in the middle of Manitoba.

The beautiful wilderness of the Grand Rapids Uplands …

… is home to a great variety of animals …

… and plants (upper left photo: Michael Cuggy).

Hydro lines span the landscape.

Limestone bedrock is very close to the land surface.

This limestone is home to many fossils.

To be continued . . . next time I will talk about the fossil collecting process, with many graphic images of dusty and hot, or cold and wet paleontologists!