By Dr. Graham Young, past Curator of Palaeontology & Geology

Those of us who live in Winnipeg know that fossils are never far away. Many Winnipeg structures feature surfaces clad in Tyndall Stone, a fossil-rich dolomitic limestone of Late Ordovician age (about 450 million years old). Tyndall Stone covers public buildings such as the Manitoba Legislative Building and the Winnipeg Art Gallery, and commercial buildings in the downtown core, but it can also be seen in thousands of homes in Winnipeg: in walls, steps, and fireplaces.

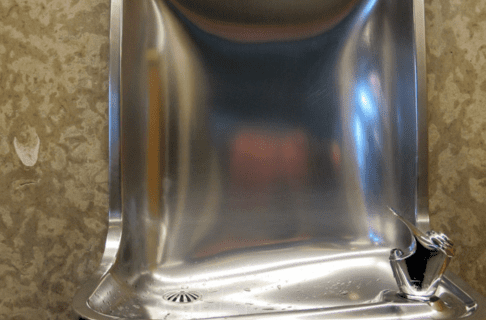

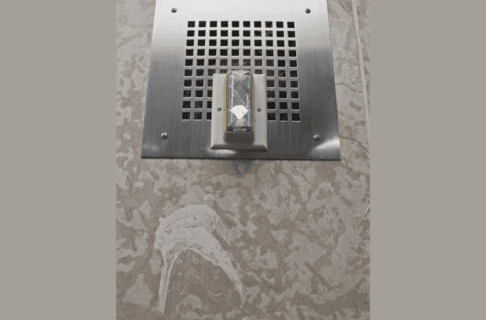

Thus, it is hardly surprising that the Museum and the adjacent Centennial Concert Hall both use Tyndall Stone inside and out. Of course Tyndall Stone fossils are represented in our Earth History Gallery, but if you think about it, it is odd that there are so many more “museum-grade specimens” exposed to the weather on the outside of the building. On the inside, as these photos show, we sometimes cover up beautiful fossils with the detritus of everyday existence: signs, fountains, alarms, and thermostats. In part, this is because the fossils are so abundant that it is hard to avoid them when placing objects, but it may also be that they are so commonplace here that people ignore them and take them for granted.

Maybe someday we will add interpretative signage to some of the better and more accessible fossils on and in the Museum, but that would be a big project to undertake. In the meantime, here is a sampling of a few of the good ones.

The hallway near the elevators may look like an unprepossessing remnant of the 1960s, but those mottled walls are thin slabs of Tyndall Stone. This stone, quarried by Gillis Quarries Limited at Garson, Manitoba, is rich in fossils representing life from an ancient tropical seafloor.

Geologically, Tyndall Stone is part of the Selkirk Member of the Red River Formation; this bedrock formation underlies much of southern Manitoba, but it is only exposed in certain places such as in cliffs along Lake Winnipeg, and in the Tyndall Stone Quarries at Garson. Behind this clock, the darker mottles represent burrows in the ancient seafloor, made by millions of little arthropods or worms. The white structure to the lower left is the colonial coral Protrochiscolithus.

The big brown blob beside the elevator is a stromatoporoid sponge. To its lower right, a smaller dome-shaped stromatoporoid (brown dome) was encrusted by the tabulate coral Protrochiscolithus (white), and to the right is a honeycomb rugose coral (Crenulites?).