Posted on: Tuesday April 30, 2019

Post by Debbie Thompson, Diorama and Collections Technician

Dioramas are incredible works of “science meets art”. Planning the layout, construction, and content often takes years, with a tremendous amount of research and collaboration with curators, diorama artists, carpenters, and electricians. Volunteers are also a vital part of the making of dioramas; they take on the mammoth task of hand painting individual leaves. But what happens after the fanfare of the grand opening? What happens as time passes by? There are just a few people to keep a close eye on them, monitoring them for insects, rodents, dust, and repairs.

As Diorama and Collections Technician, I am one of those people. One of my main tasks is the maintenance and repair of the dioramas. Many people, of all ages, want to know if what they see in a diorama is real or not. The temptation to reach in and just test a blade of grass, flower, or a leaf on a tree is enticing. Sometimes, damages occur as a result. Then it’s time for repairs.

Along the fence of the rye field diorama is a thin section of prairie. All the tall grasses and flowers are within reach of visitors, and over time, the combination of accidental and intentional handling had led to the degradation of this section of the diorama. What was once a tall grass prairie has been beaten down to a matted mass of broken, unrecognizable stems.

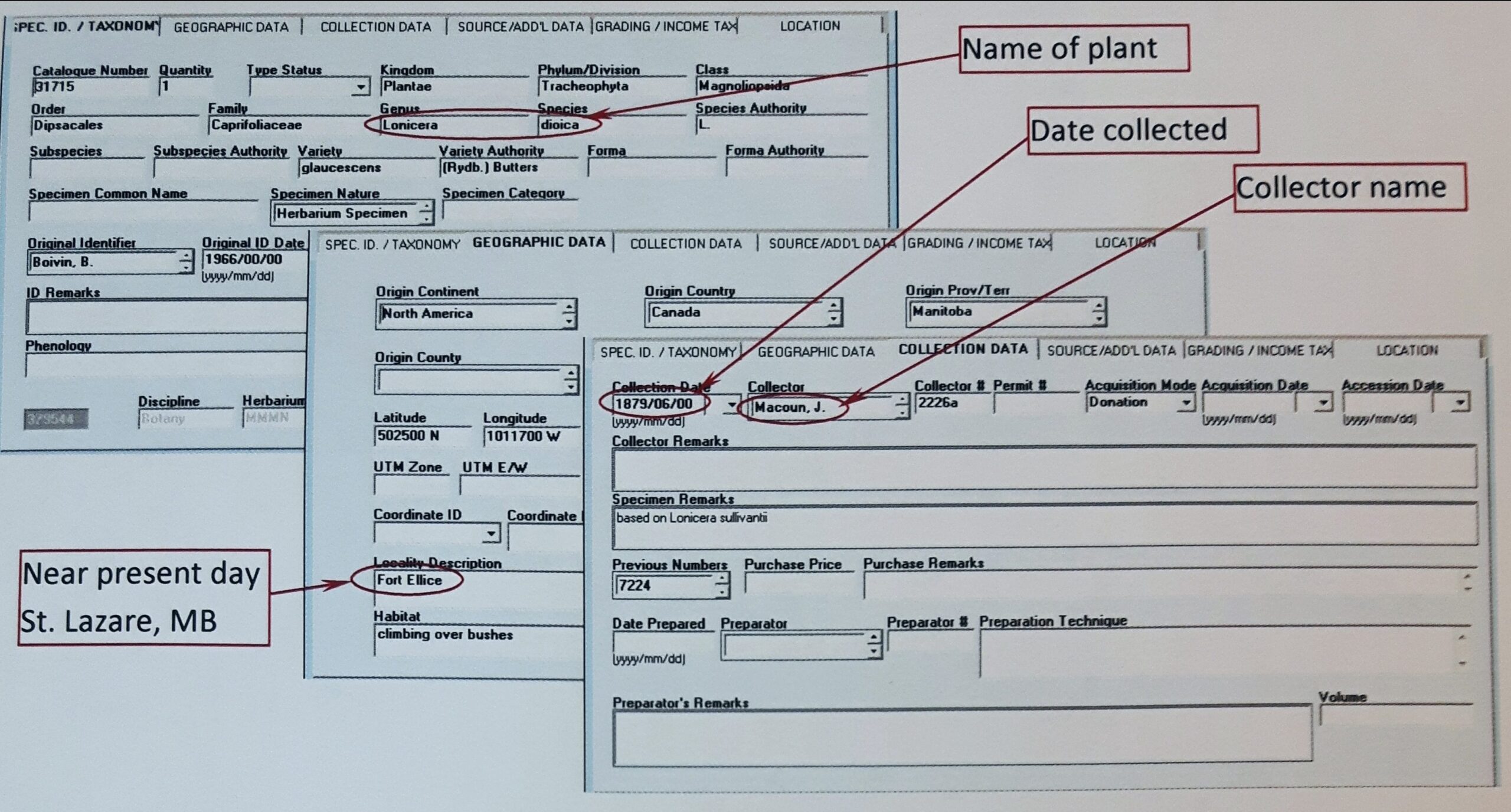

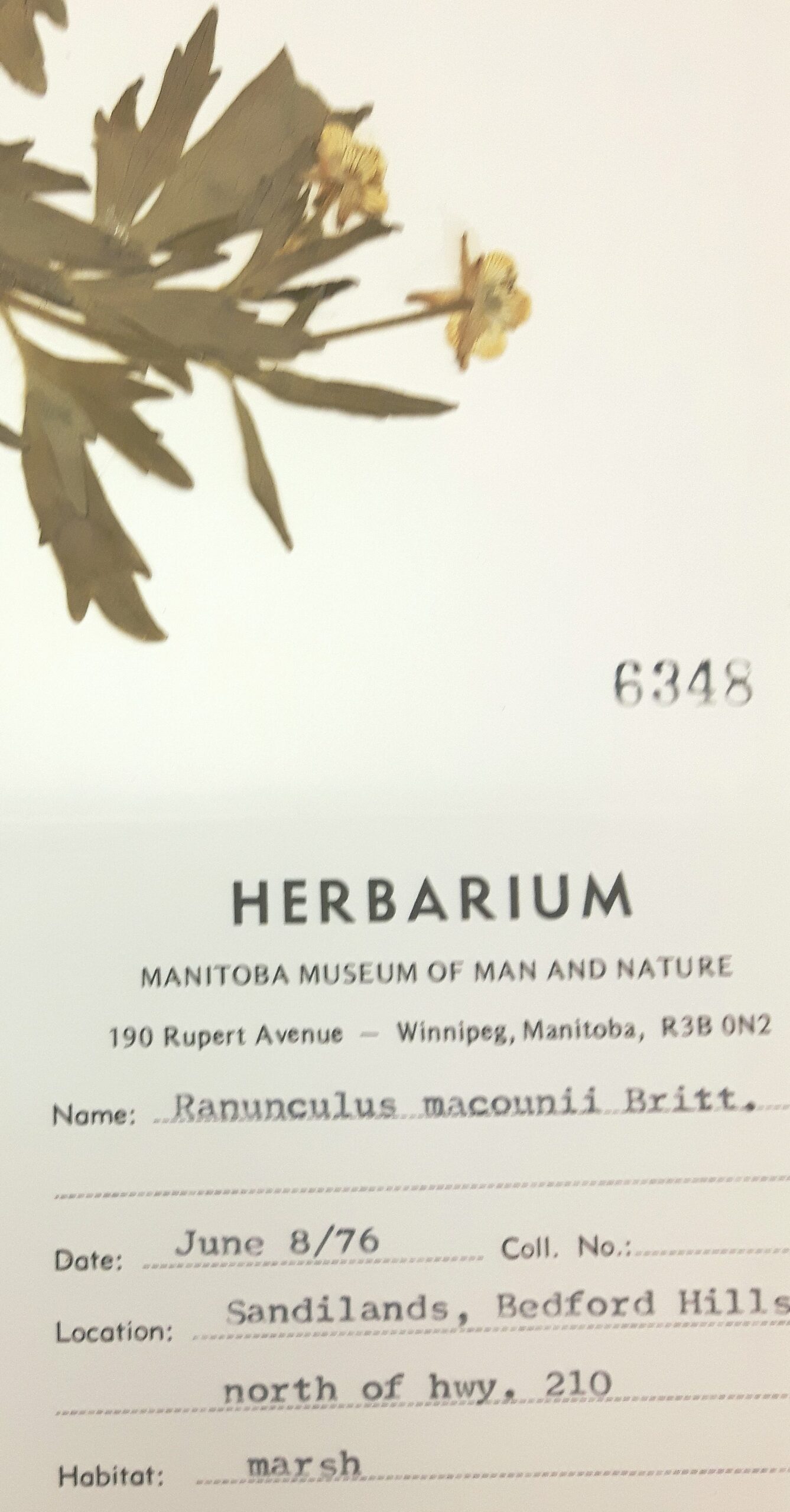

Knowing where to collect the plant materials, receiving permission to collect in that area, ensuring what I’m collecting isn’t endangered nor threatened, and then processing the plant materials to preserve them is only the first step in repairing the damage. Once the plant material is preserved, its original colours have faded, so the plants must be painted “back to life”. Before the plants were even picked, detailed notes on colour are taken so when the plant is painted, it resembles its living counterpart.

Once the plant materials are painted, then it’s time for the repairs.

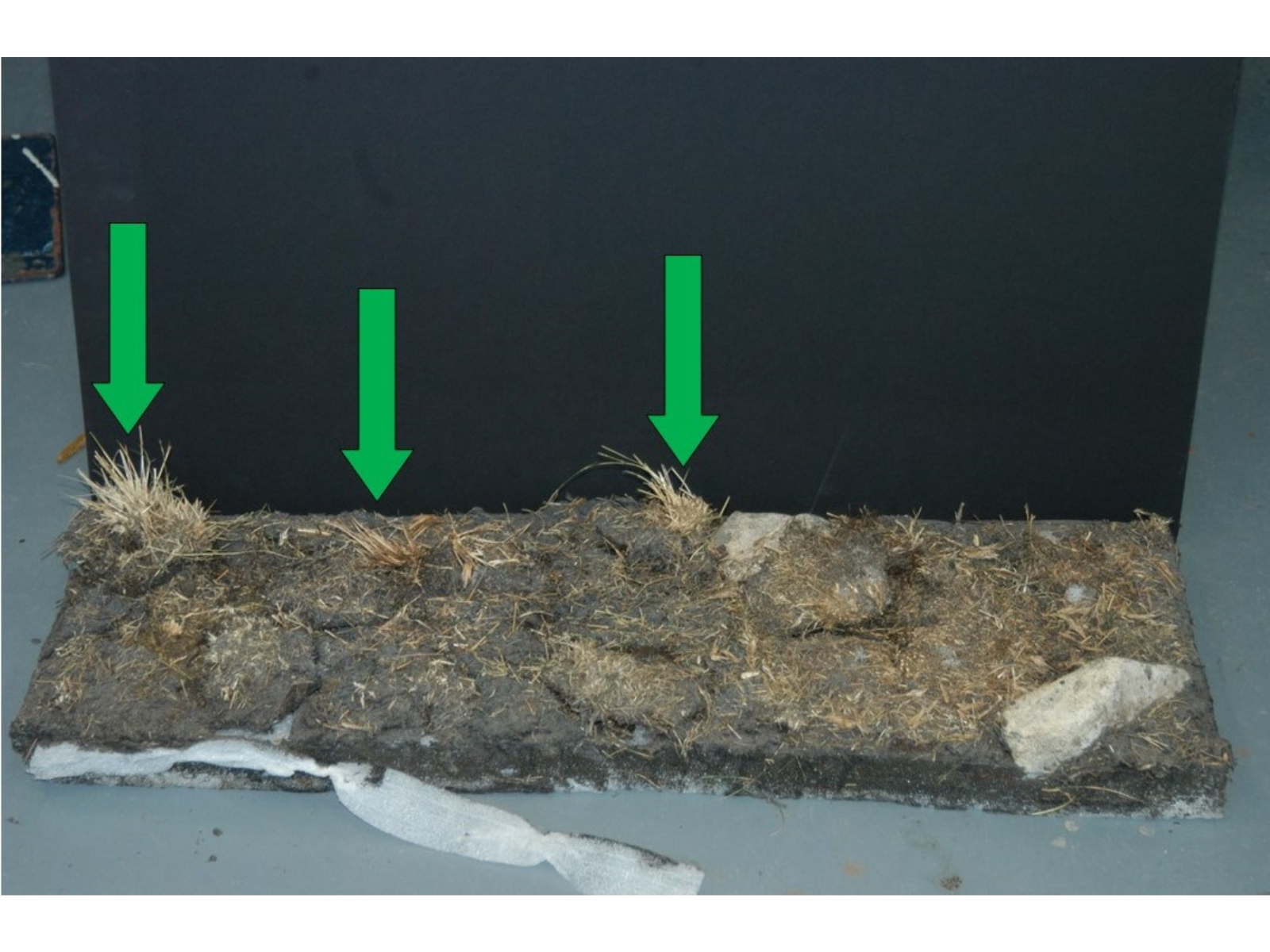

This piece of the diorama has been removed from along the fence that is easily accessible to visitors. The foam base had been painted a dirt colour, and originally it had clumps of tall grasses and flowers. But now, the plant material lies broken. © Manitoba Museum

I removed all the broken grasses and stems, revealing a few of the original stumps of grass clumps (green arrows). However, these clumps cannot be reused and so must be removed. © Manitoba Museum

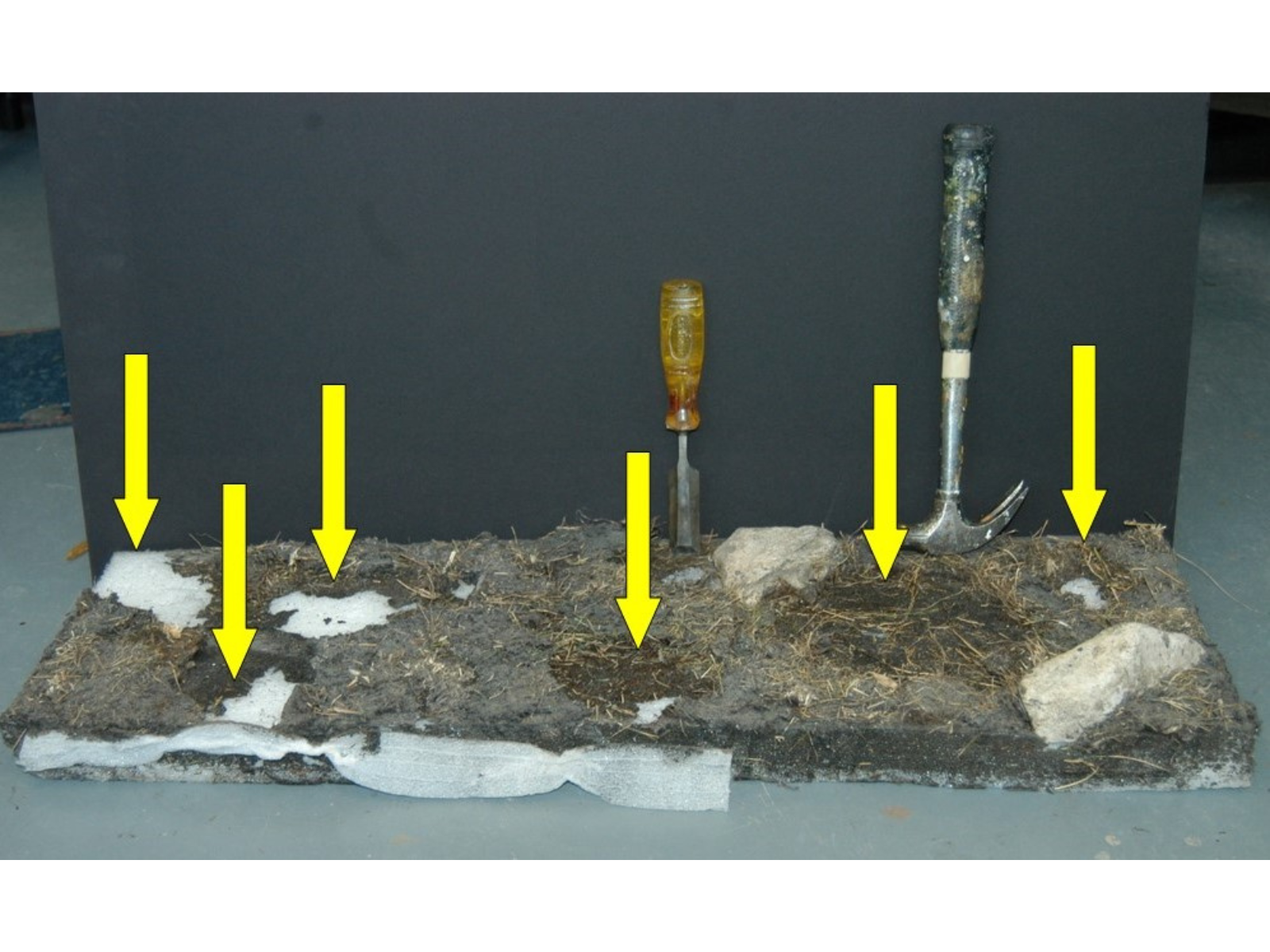

All the grass clumps are removed with a hammer and chisel (yellow arrows). Not only would it look unnatural to have broken grass clumps, but a level surface to work with is needed for the repairs. The exposed white ethafoam will have to be painted back to a “dirt” colour. © Manitoba Museum

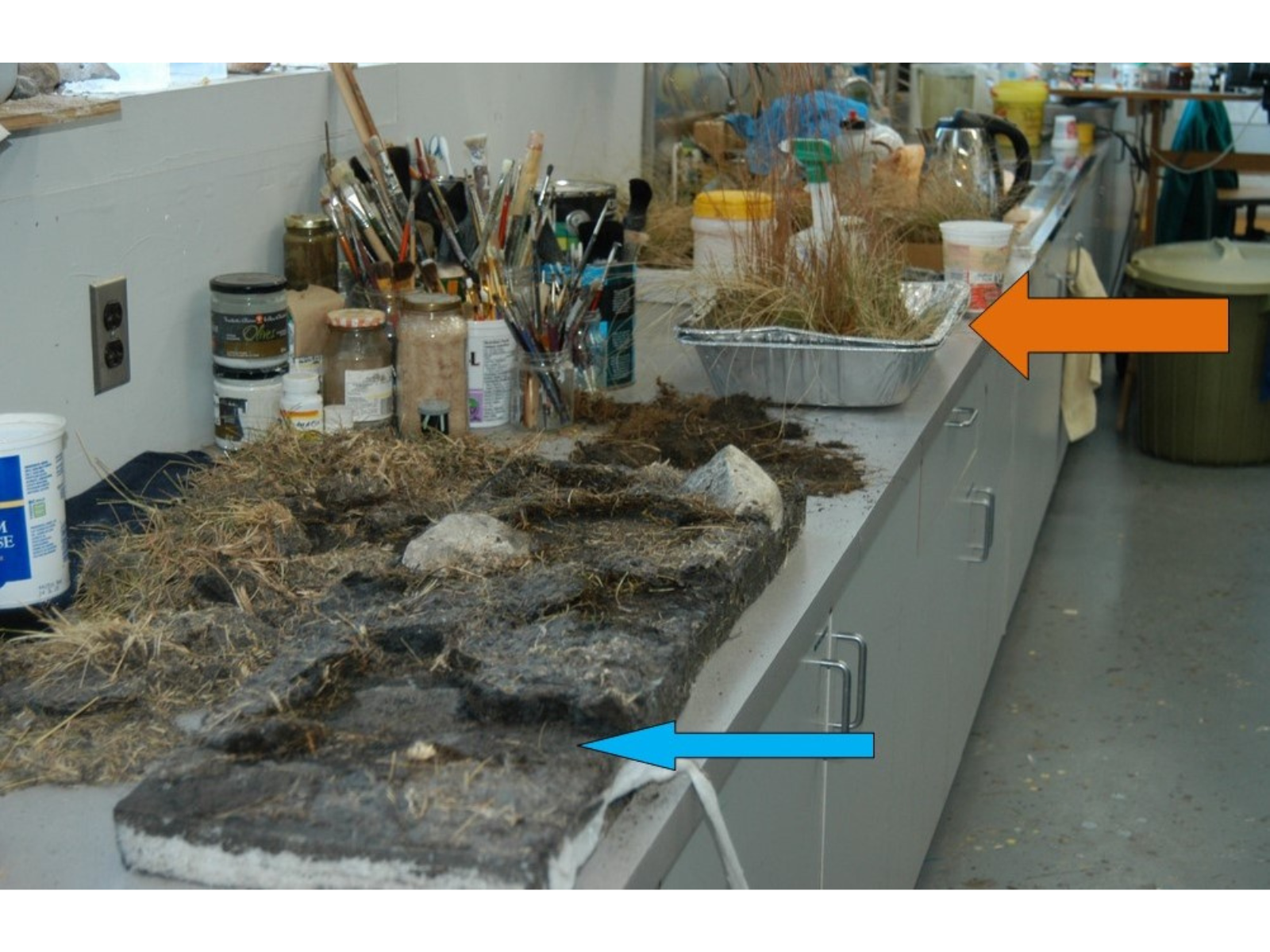

Here you can see that the exposed ethafoam has been painted a dirt colour and then allowed to dry (blue arrow). In the aluminum trays is a special solution that the grasses are soaking in (orange arrow). The soaked grass clumps are placed in the chiseled out areas. When the solution dries, it dries clear and hard, cementing the grass clumps in place. This will in time have to be removed the same way, with hammer and chisel, as damages build up. © Manitoba Museum

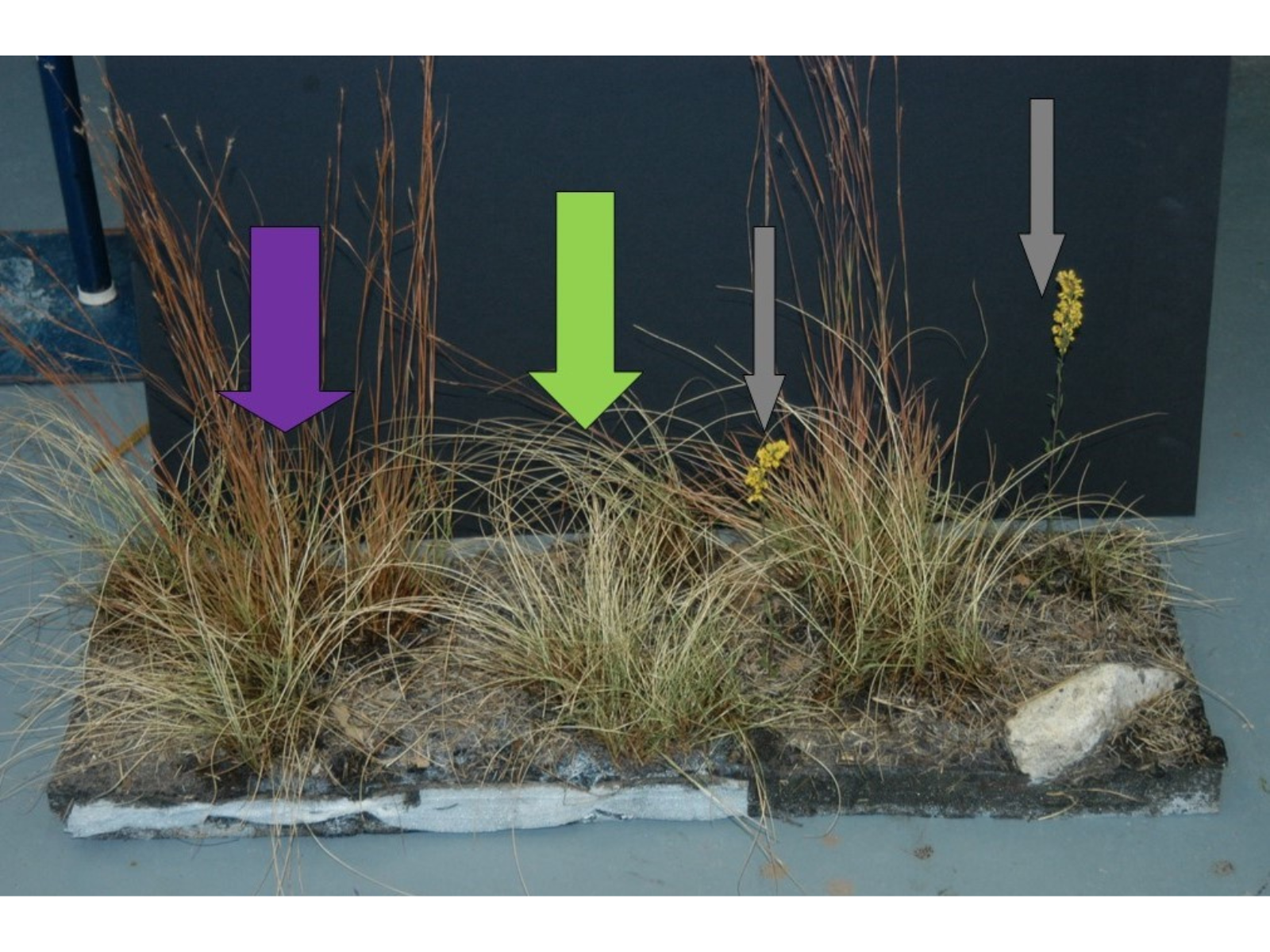

Here is a newly repaired section of prairie, with Little Blue Stem (purple arrow ), Stipa (another type of prairie grass, green arrow) and Slender Goldenrod flowers (grey arrows). Extra dirt was placed between the newly installed grasses, with sun bleached grass debris sprinkled over top. © Manitoba Museum

From start to finish, this one piece took just over 2 hours to repair. In all, there were 9 pieces that had to be repaired in this fashion.

Many of the dioramas are composed of real, once living plant materials that have been responsibly harvested and preserved using different chemicals and techniques. Examples of these types of plants include the aspens in the rye field and elk dioramas and mosses and spruces in the Boreal Gallery. However, the green, living looking plants are made of plastic, such as the many plant species in the wolf den diorama. And then there are combinations, like a real stem but plastic flowers, such as the Black-Eyed Susans in the rye field diorama.

I hope this blog gives you a better understanding of what goes into maintaining the dioramas at the Manitoba Museum.