Posted on: Friday December 18, 2020

As you may have heard, on December 21, 2020, the planets Jupiter and Saturn will be very close together in the sky, an event called a conjunction. Because this coincidentally is happening on the same day as the winter solstice, and only a few days before Christmas, a lot of media have dubbed this the Christmas Star. There’s been some confusion about what exactly that means and how you can see this event, so here’s a handy reference guide to the whole thing.

What is happening?

The planets Jupiter and Saturn will appear very close together in the sky, almost touching, on the early evening of December 21st, 2020. This kind of event happens about every 19 years, when Jupiter passes Saturn as seen from the Earth, while all three planets are in their orbits around the Sun. However, usually the passage isn’t this close – so, we haven’t had a Jupiter-Saturn conjunction this close since the middle ages.

When can I see it?

It’s actually in progress already – Jupiter and Saturn have been visible in the evening sky for months, slowly moving closer together as Jupiter catches up to slower-moving Saturn. Over the weekend of December 18-20 the two are already closer together than the apparent size of the Moon in the sky. Each night they will be closer together, leading up to closest approach on the evening of Dec. 21, 2020. After the 21st, Jupiter will move farther away from Saturn night after night. The Manitoba Museum will be doing a live-stream telescope event on the early evening of December 21 so you can see the planets up close and in detail.

What will it look like?

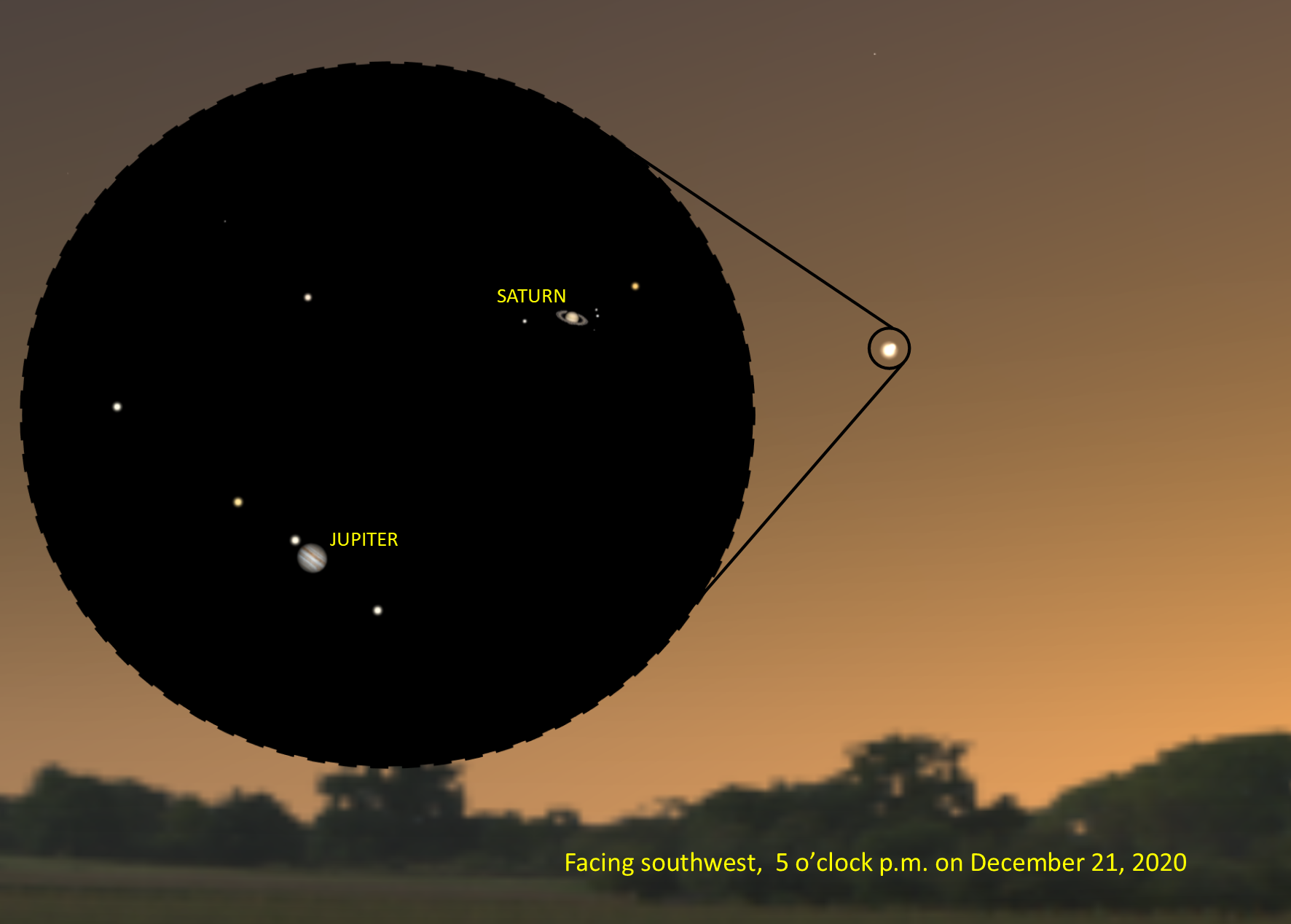

With the unaided eye, you can see Jupiter as a bright white “star” in the southwestern sky right after sunset. Saturn is quite a bit fainter, and has more of an off-white colour. In the days before closest approach you’ll easily distinguish them as separate objects. On the evening of closest approach, most people will still probably be able to see them as two separate objects (unless you have less than 20/20 vision).

In a small telescope, you’ll be able to see both planets at the same time in a low-power eyepiece. As the sky darkens, you’ll also see some of the moons of Jupiter and Saturn appear. The Manitoba Museum will be doing a live-stream telescope event on the early evening of December 21 so you can see the planets up close and in detail.

What’s all this about a Christmas Star, then?

That’s… complicated. The common image many people have of the Christmas Star comes from many different sources. The Christian Biblical story of the “Star of Bethlehem” actually doesn’t say much about what the “star” looked like, but centuries of art and Christmas card images have turned it into a huge blazing beacon in the heavens. This event will not look like that. (See “What will it look like?” above.) The Star of Bethlehem actually wasn’t something that everyone saw – it was only the Magi, the “wise men from the East” who saw it. That alone tells us it probably wasn’t as simple as a bright light in the sky.

There are some theories that suggest that the “wise men from the east” were astrologers, and so they would have been excited about things like planetary conjunctions, things that were seen as significant but not immediately noticeable to the casual viewer. Things like planetary conjunctions would have been highly significant to the Magi, especially if they were rare events or repeated events. If we run with this hypothesis, there was a conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn in 7 B.C. – actually, there were three of them, in an even-rarer triple conjunction. This actually times out fairly well to match the Biblical account, since we know that the 8th-century monk who did the math to calculate the year 1 A.D made some errors and was off by a few years – the Nativity story probably actually occurred a few years before 1 A.D. in our current calendar. For example, King Herod, who was alive during the Nativity story, actually died around 4 B.C., so we know the story had to take place before then.

If this idea is correct, the wise men saw the triple conjunction in 7 B.C., interpreted it to mean there would be a royal birth in Judea, and traveled to the land of King Herod. King Herod had no idea what they were talking about – his court astrologers had not seen a “star” that they thought was important. (Neither did Chinese astronomers of the day, who took meticulous observations of any new objects like comets, new stars, and the like.) The wise men leave Herod and travel to Bethlehem, arriving sometime in 6 B.C. or perhaps a bit later.

None of this is certain, of course – there are other possible explanations for the Star of Bethlehem, like a conjunction of Venus and Jupiter in 2 B.C. that would have been the brightest star in the sky. And given the nature of the Nativity story, there isn’t enough evidence to even say whether the Star was an astronomical object, a divine inspiration, an interpretation by the wise men, or an idea added in later revisions of the Bible throughout the ages. And really, not everyone feels the Star of Bethlehem needs an explanation in the first place. As I said, it’s complicated.

So, because it’s possible that the Star of Bethlehem was inspired by a rare triple conjunction of planets in 7 B.C., and because this year we are seeing a single conjunction of the same planets Jupiter and Saturn, which happens to occur in December, the Great Planetary Conjunction of 2020 has been dubbed the Christmas Star. And so many people are expecting the Christmas Card version of the event: a huge light in the sky.

Conclusion

To some, the actual Planetary Conjunction of 2020 will fall short of their expectations. To others who attach religious significance to the idea of a Christmas Star, it might disappoint as well. But consider what is happening: humans, a part of the universe that has become alive and aware, are standing on a ball of rock hurtling through space, looking out at the two largest planets in our solar system. On December 21, 2020, those two planets will be lined up from our viewpoint, so that they will both be visible in a telescope at the same time – a very rare and pretty cool event to watch. In the days before and after, we can watch the clockwork of the heavens tick forward night after night, as the relative position of the Jupiter, Saturn, and Earth change as they orbit the Sun. Right now, a human-made robotic spacecraft is in orbit around Jupiter, beaming back close-up pictures of a gas giant planet covered with storms larger than the Earth. On some of the moons of the two planets, there may in fact be some form of primitive life, living there now: in the underground oceans of Europa, for example, or the thick atmosphere and methane seas of Titan. And we can participate in these grand cosmic events just by going outside and casting our eyes upwards on a clear winter’s night. I think that qualifies as a miracle of sorts, no matter what your beliefs are.

First step: educate yourself. Pick up

First step: educate yourself. Pick up