Posted on: Tuesday April 2, 2013

Last summer I went to Spruce Woods Provincial Park to determine which insects pollinate the rare Hairy Prairie-clover plant, a species that only occurs in sand dunes. Oddly enough, even though Hairy Prairie-clover is rare, it was being visited more frequently than some of the common plants I have observed. But there was a dark side to all that activity: it was drenched in blood-the blood of innocents! Instead of the cute, fuzzy little bumblebees I had grown accustomed to watching, I encountered big, black and yellow or red wasps and large, colourful wasp-like flies! What were those crazy creatures? When I got my insect identifications back recently, I was shocked to discover that 40% of the species and 67% of the insect visits to Hairy Prairie-clover were by solitary hunting wasps and parasitic flies that prey on other insects.

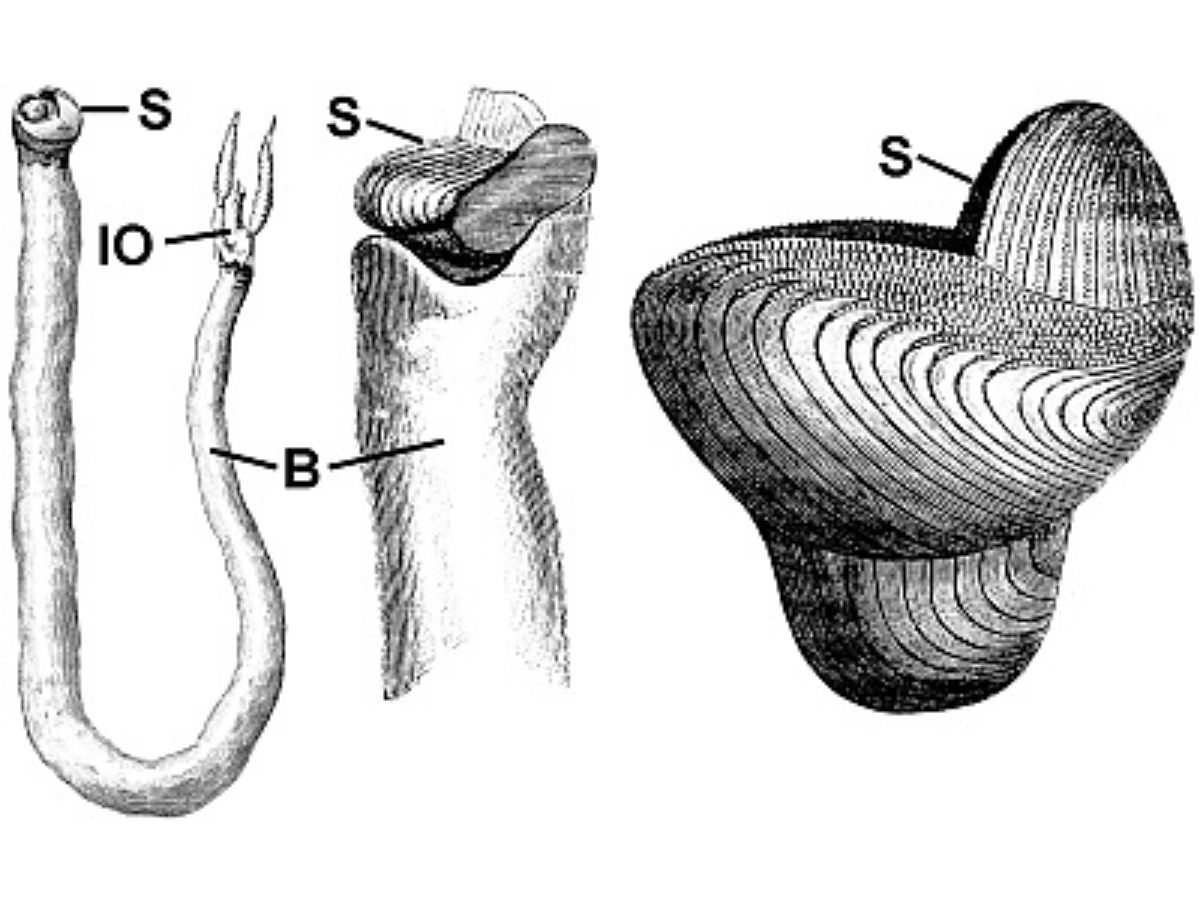

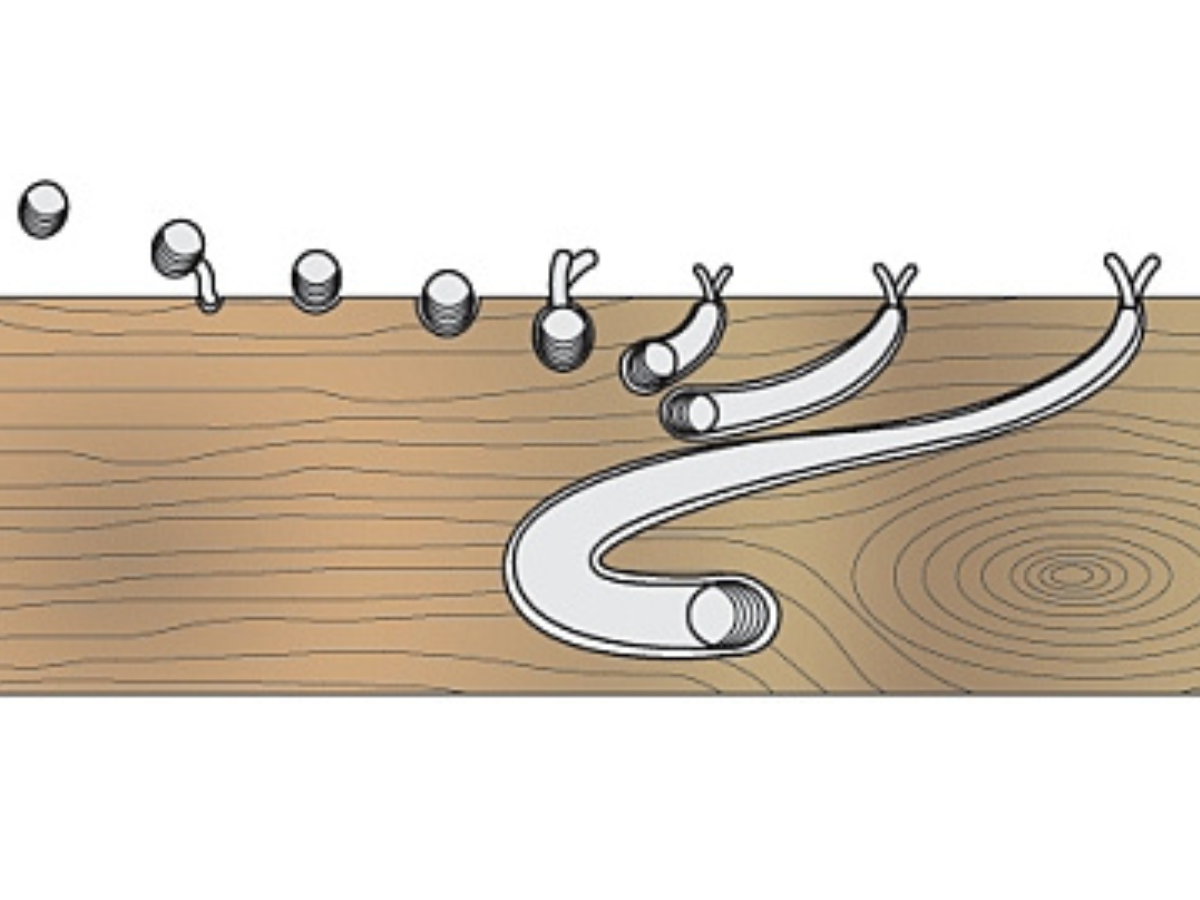

The Sand Wasp (Bembix pruinosa) was the most frequent flower visitor to Hairy Prairie-clover. Although adult Sand Wasps consume pollen and nectar, the females also capture and paralyze small flies (e.g. Soldier and Horse Flies) to feed to their babies. The Sand Wasp larvae and paralyzed prey are well hidden in underground burrows. A related species of wasp called a “bee-wolf” (Philanthus sp.) was observed capturing and flying away with tiny Andrenid Bees (Perdita perpallida) that were busy pollinating Hairy Prairie-clover.

Sand Wasp on Hairy Prairie-clover.

A small Sweat Bee unaware of the fact that it is about to become a wasp’s breakfast.

The Common Thread-waisted Wasp (Ammophila procera) is also a solitary hunting wasp but captures the caterpillars of Noctuid moths called Prominents (Notodontidae) instead of flies. A similar looking species, the Great Black Wasp (Sphex pensylvanicus), captures and paralyzes grasshopper or katydid larvae, and lays an egg on it to act as baby food. The Grasshopper Bee Fly (Systoechus vulgaris) also parasitizes grasshopper eggs. The female Grasshopper Bee Fly shoots her eggs in an area of loose soil suspected to contain grasshopper eggs. The hatched larvae crawl around in the soil until they find a suitable grasshopper host and then they suck it dry!

Similarly, the larvae of large Scoliid Wasps (Trielis octomaculata), are ectoparasites on Scarab Beetle (Scarabaeidae) larvae. The large females hunt down the beetle larvae in the soil, paralyze them and lay an egg on them. Some Scoliid wasps have even been used for the biocontrol of white grubs on sugar cane crops.

Katydid resting on Hairy Prairie-clover; another unsuspecting victim!

The predatory Scoliid Wasp enjoying some pollen!

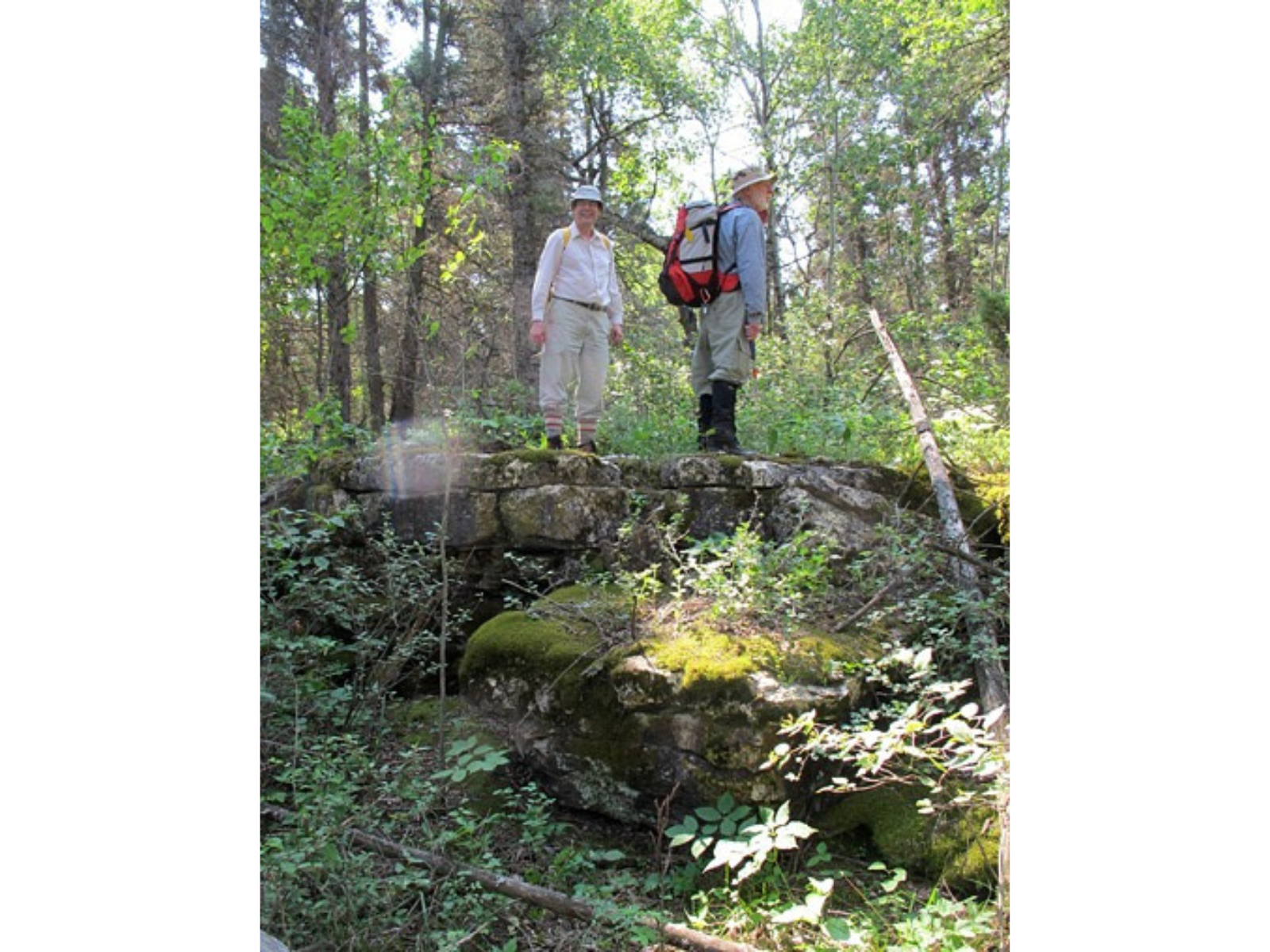

Many wasps have their burrows in loose sand on the dunes.

And those wasp-like flies? They were Conopid or Thick-headed Flies. The female flies lay their eggs inside bees or wasps. The hatched larva then slowly eats its host until it dies, eventually bursting from the exoskeleton after pupation.

Ironically, even the parasitic wasps are themselves parasitized. The females of the Bee Fly Exoprosopa shoot their eggs into the burrows of solitary hunting wasps, and the hatched larvae develop as external parasitoids. What a fascinating series of biological interactions surrounding just a single plant. Clearly it’s an insect-eat-insect-eat-insect-eat-plant world out there!