As we enter June, Manitobans spend time outside gardening at home or swimming at the cottage, except for herpetologists (reptile and amphibian scientists) when June is time to look for toads! This is a good month to be listening for Great Plains toads (Anaxyrus cognatus) and plains spadefoot toads (Spea bombifrons) as males gather in wet spots to call and attract mates. These two species are almost unknown to most people, despite being found in good numbers if you look and listen in the right places, and their “love songs” can carry for over two kilometres! But they are overlooked because they generally don’t call until it is dark, and in June that means well after 10 pm; most of us (if you are not a herpetologist) are inside avoiding mosquitoes and likely getting ready for bed.

Another reason these two toad species “call under the radar” is that their ranges are restricted to the southwestern corner of the province. As many Manitobans head east to lake country, they are missing one of nature’s incredible sound and light shows – hearing dozens of each these two species calling together under a clear, moon- and starlit prairie sky is a special experience. Here’s a taste of that sound (you might want to turn the volume down!):

The metallic trill in the foreground is a Great Plains toad and in the background are the nasal snores of plains spadefoot toads. These were calling from a temporary wet spot in a farmer’s field near Melita.

Great Plains toad (left) and plains spadefoot toad (right) with inflated throat sacs calling to attract females. These species are southwestern specialties and not found elsewhere in Manitoba. The bodies of these males are under 60 mm long.

© Randall Mooi

The ecology of Manitoba’s southwest is unique and worth exploring. In addition to these two toads, there are many species of plants, birds, mammals, and invertebrates that are found nowhere else in Manitoba. Birds and mammals are always the most obvious to people, but smaller creatures like amphibians make up a considerable portion of the wild animal biomass of the southwestern corner (perhaps equalling that of small mammals and exceeding that of birds). In wet years, the numerous temporary ponds, prairie potholes, and other wetlands provide habitat for amphibians to breed and lay eggs, and for their larvae to grow and transform into frogs, toads, and salamanders. Once adult, most Manitoban amphibians are essentially terrestrial, returning to wetlands only to breed and lay eggs.

Great Plains toads and plains spadefoot toads are no exception, and avoid detection by people and predators by spending much of their lives buried underground. During our cold winters, these two species need to hibernate below the frost line. They are good diggers and can burrow into softer ground or sand – spadefoot toads are so-named for the hard, keratinous, sharp-edged bumps on their back feet that they use as “spades” to dig backwards into the soil. Great Plains toads are also known to use old rodent burrows to get underground. In spring and summer, when it can be hot and dry on the prairies, these two species escape the searing heat by remaining below ground during the day and hunting for food at night when it is cooler. Even then, they often remain buried for long periods to retain moisture and come to the surface only after heavy rainfalls to breed.

Northernmost record of Great Plains toad in Manitoba (top; © Peter Taylor, used with permission), found crossing the road at 4 am (yes, surveys can run from 10 pm to dawn the next day!).

Typical habitat for our southwestern toads (bottom; © Manitoba Museum).

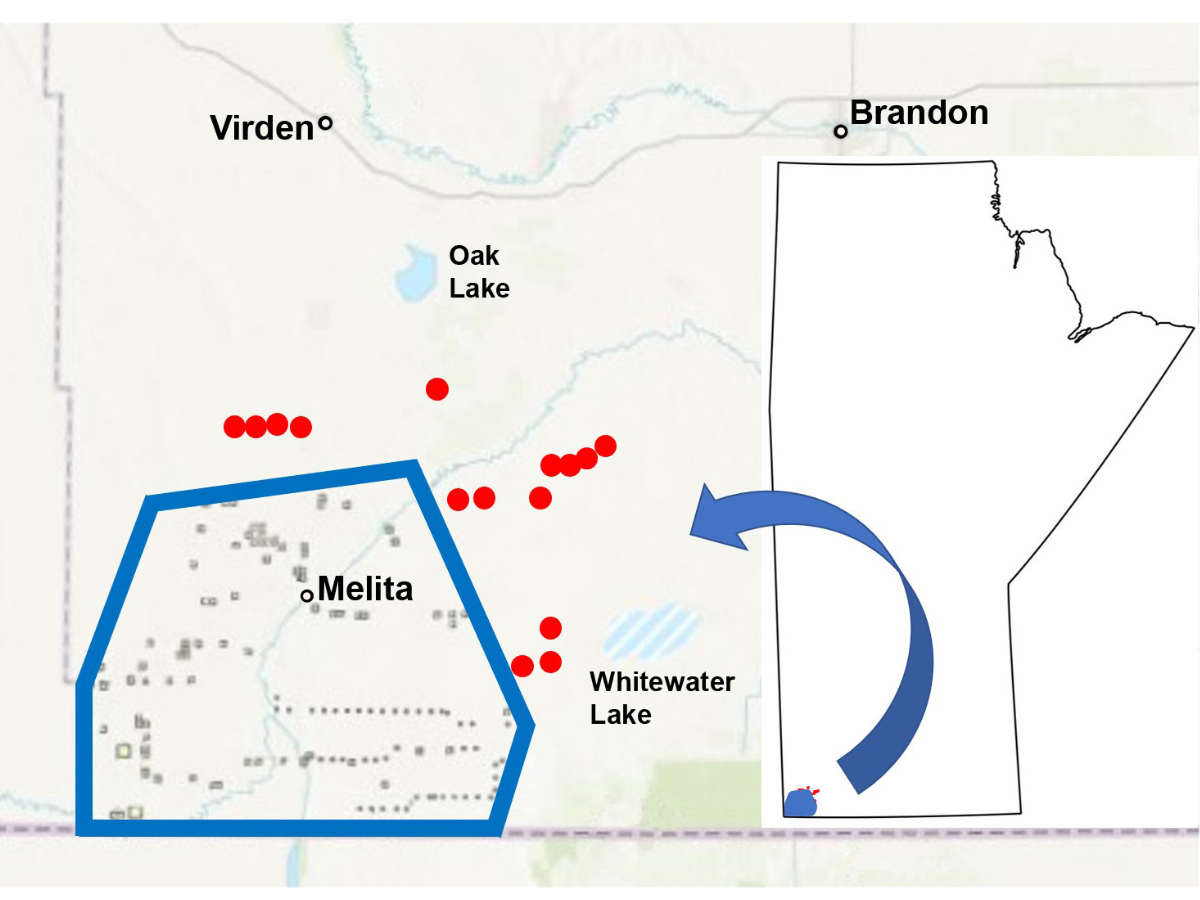

The Manitoba Museum is studying the Great Plains toad because it is considered threatened in Manitoba. For many animals in the southwest of the province, loss of habitat and pollutants are concerns because much of our original prairie landscape has been considerably modified by commercial agriculture, resource extraction, and transportation corridors – all through the demands of our modern lifestyles. Some good news, though, has come through research at the Museum, where Great Plains toads have been found to have a larger distribution than originally thought. Last spring’s heavy rains meant that there were many temporary ponds providing suitable habitat, even in places that are usually quite dry. The result was that toads in these areas, likely inactive as breeders for several years, had opportunities to attract mates and reproduce. Museum researchers discovered the species at several new sites, some up to 25 km outside of the previously known range!

The previously known range of Great Plains toad (in solid blue on the inset map of Manitoba; bounded by a blue line on the close-up of the southwest corner), with red dots showing the new sites discovered last spring by Museum researchers.

Base map modified from data provided by the MB Conservation Data Centre, used with permission. © Manitoba Museum

Within this revised distribution of Great Plains toads, plains spadefoot toads were found throughout and in higher numbers. Both toad species, despite the extensive use of pesticides and loss of habitat, seem to be surviving today’s highly modified conditions, but how successfully remains guesswork. Without consistent monitoring programs, it is impossible to measure the size of toad populations or to determine if their numbers are stable, increasing, or decreasing. And because spadefoots and Great Plains toads adjust breeding activity to cycles of drought and wet periods, it is a huge challenge to determine population sizes. In wet years, like 2022, the toads seem to be everywhere, but in a dry year they seem to disappear. This means that monitoring programs need to be maintained over long periods through several wet/dry cycles. And climate change is making these even less predictable.

Installing recording units and data loggers on hydro poles (with a permit, of course) near suitable habitat (left). A white data logger mounted above a green recording unit beside a temporary pond (right).

© Manitoba Museum

The Manitoba Museum has just begun a pilot project to monitor these two amphibian prairie specialists. Automated recording units have been set up at a handful of locations where Great Plains and spadefoot toads have been found in previous years and where temporary ponds existed at the time the units were deployed, all with the hope that this will increase detection rates. The units are set to record at particular times over each 24-hour period throughout the spring and summer months. Temperature and humidity loggers are paired with the recording units. The goal is to determine what triggers breeding activity in the two species, what times of the year it occurs, and in what numbers. These data will help determine measures that can conserve these two toads and, perhaps, other species that rely on similar habitat.

We hope that this will mean that Manitobans can go a-toad hunting and experience their incredible chorus on the prairies in perpetuity.

And, of course, everyone has the opportunity to visit the Museum’s new Prairies Gallery to learn the calls of prairie toads and frogs and explore their fascinating life histories – above and below ground!