Posted on: Friday March 15, 2024

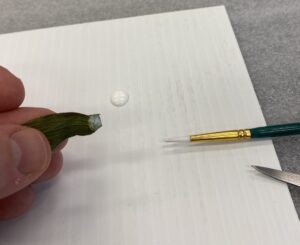

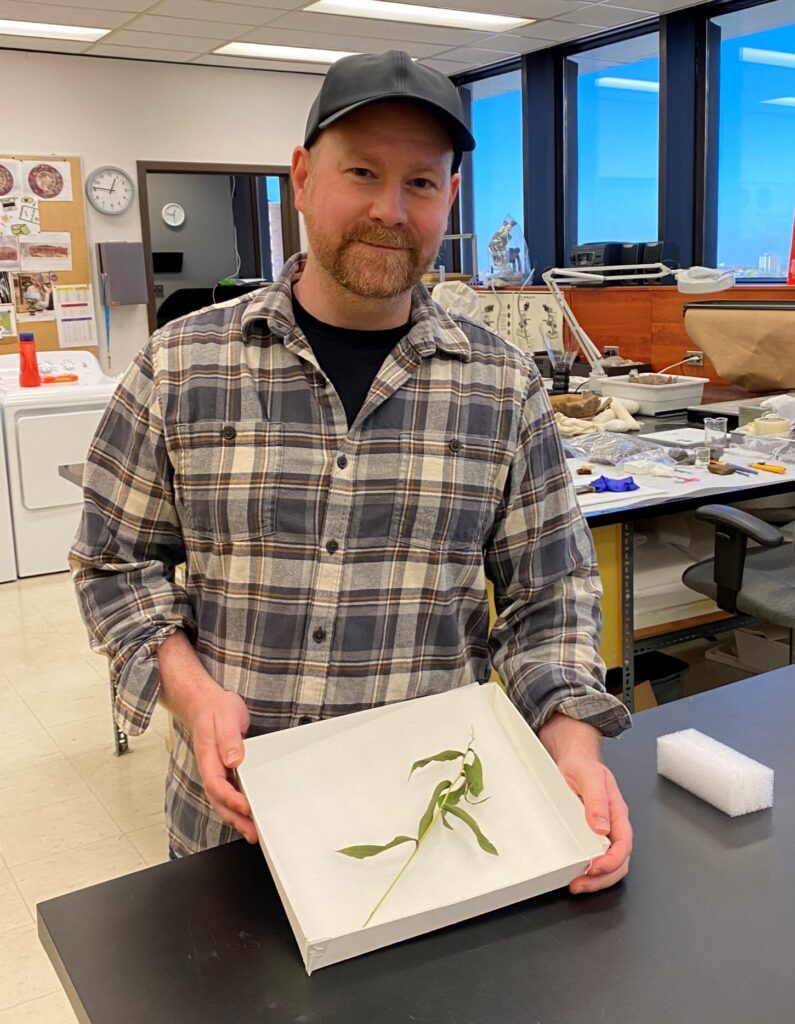

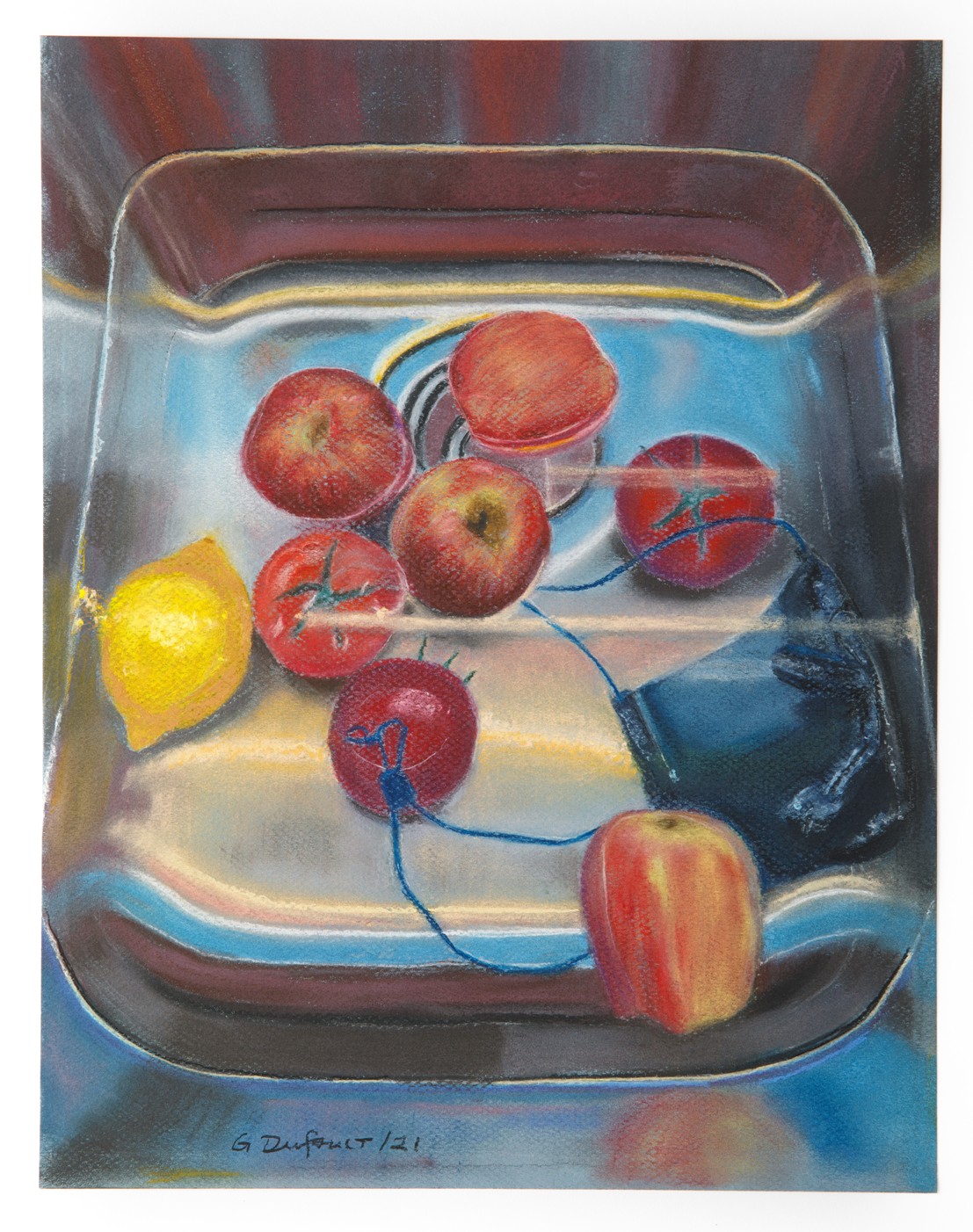

The tools Conservator’s use to fix, repair, and clean objects in a Museum collection are pretty unique, in that many of these items come from different professions or have been custom-made to suit the job. During a recent behind-the-scenes tour I was asked about the tools I had laid out in my tray, stuffed into foam to protect the sharp edges, and things that looked a bit like they came from another planet. I thought I would share some of the tools used in the Conservation lab, as a way to spark imagination and inspiration for anyone that has been stuck on a project not knowing what tool could be right for the job!

Can’t touch this …

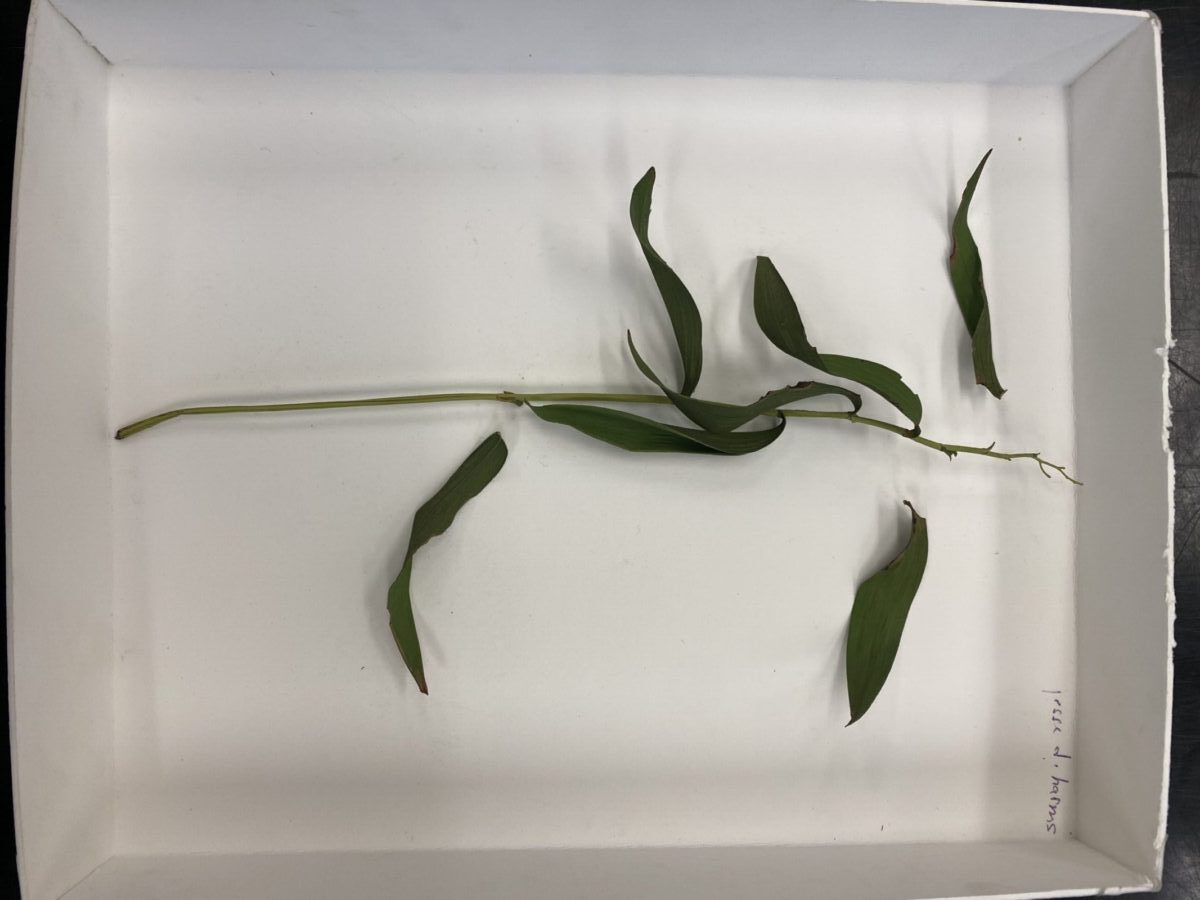

The first item that I am deeply passionate about are my purple and pink scissors. Everyone in the lab knows that if you borrow these purple and pink scissors to make sure to return it to the tray immediately, as I am very invested in these little tools! These small delicate scissors, come from the cosmetic industry and are mostly used by estheticians. Slightly curved, incredibly sharp, and a very fine pointed tip, these scissors work magic for repairing textiles, cutting extremely detailed molds and casts in reproductions, and any other work that needs an accurate slice.

Say “aaaahhhhhh” …

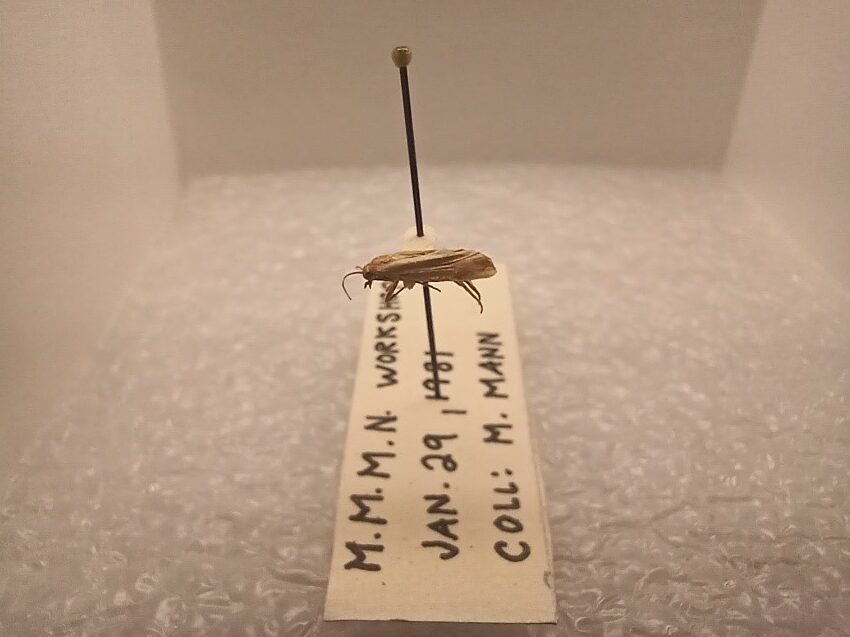

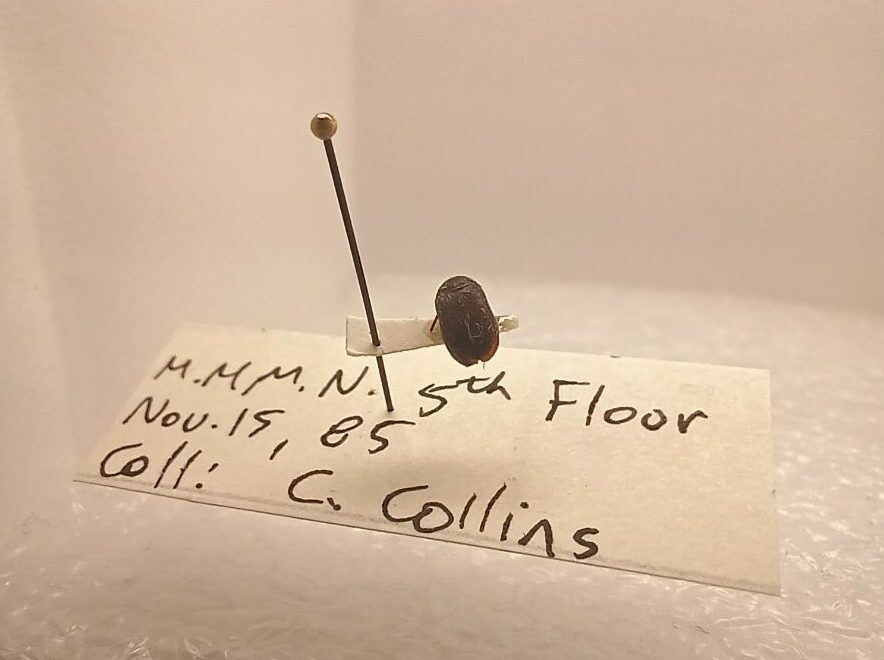

Dental tools would be the next array of instruments that we use in the Conservation lab. Not only are dental tools good at cleaning your teeth but they are great for cleaning objects! Caution is used however when we pick-up these strong metal tools, because they can cause damage if used on an improper object. Dental picks and scrapers are often used on wooden objects, when there is something deep in cracks or crevices that needs to be removed.

Let’s get digital .. digital …

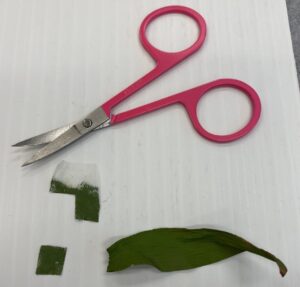

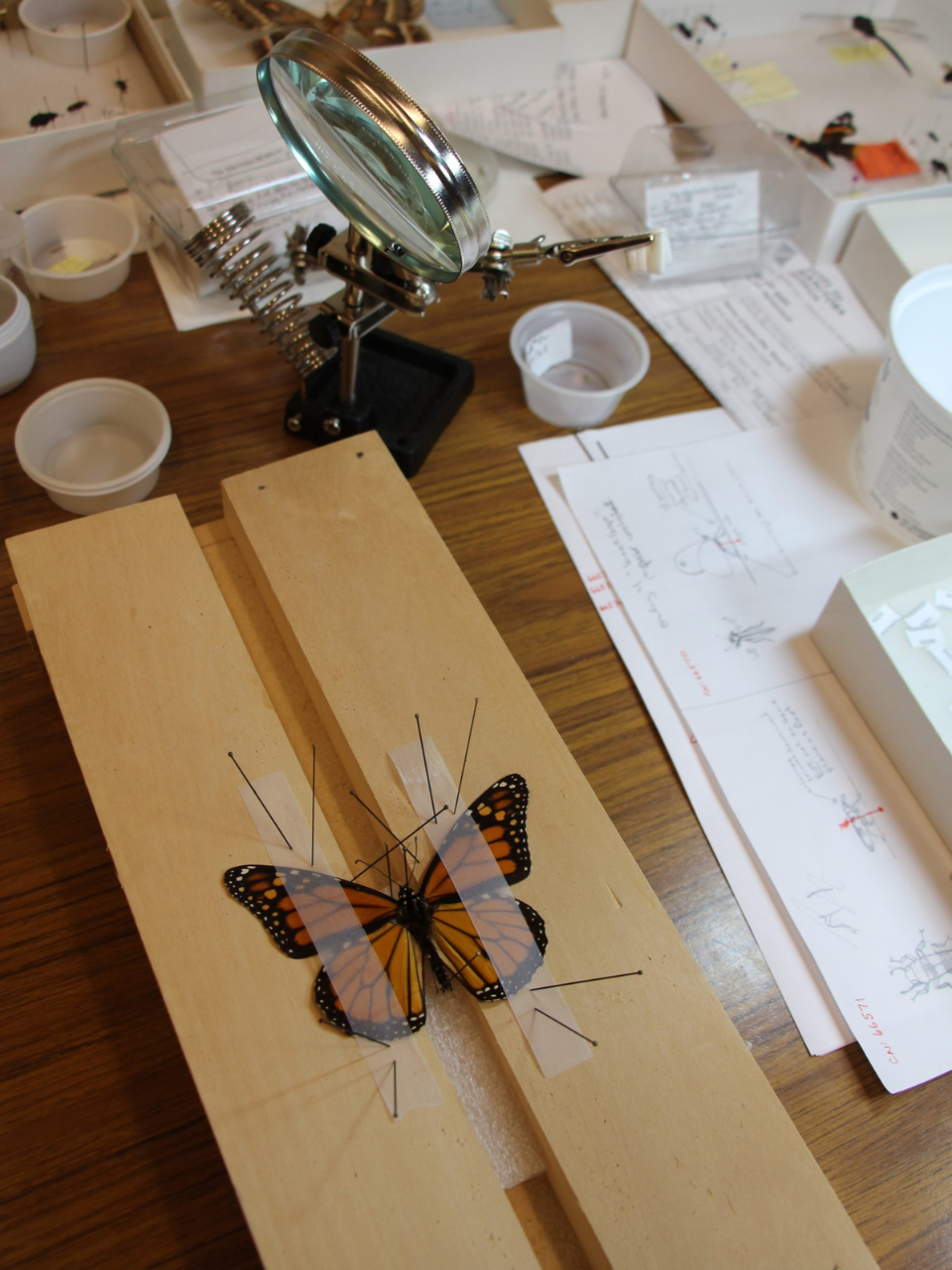

Diving into a different industry that Conservator’s seek tools from, would be the world of circuit boards and computer repair. The glass bristle brush is about the size of a pen, and has a fibre glass tip that is adjustable in height depending on the work being done. Archaeological metals, such as brass buttons or thimbles, are where these fine detailed tools work well to burnish or remove corrosion products. A few cautions are followed when using a glass bristle brush, including wearing a respirator, safety glasses, and protecting the body with a lab coat. The fine glass bristles break off as the tool is brushed back and forth, which is why safety is of utmost importance.

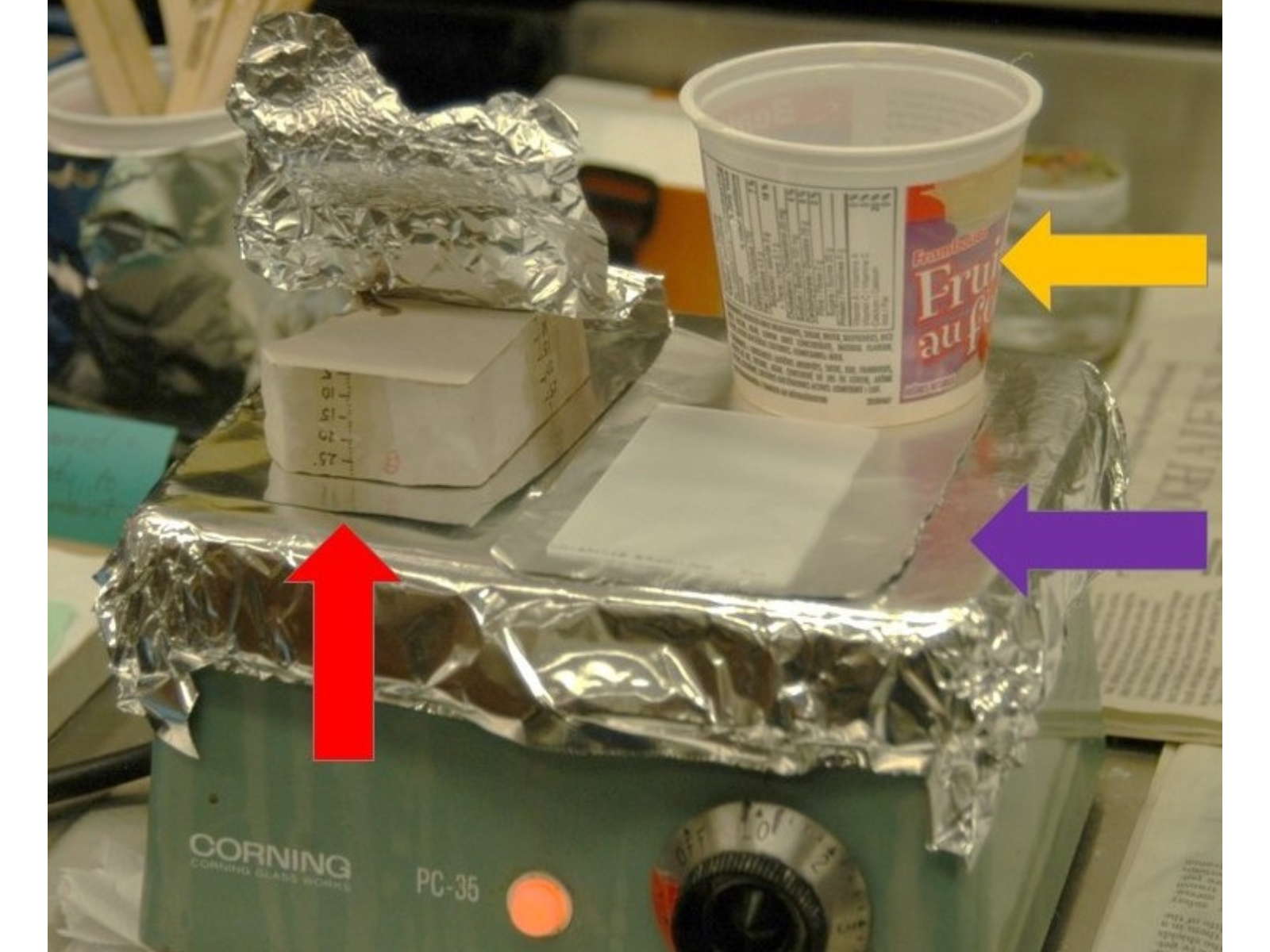

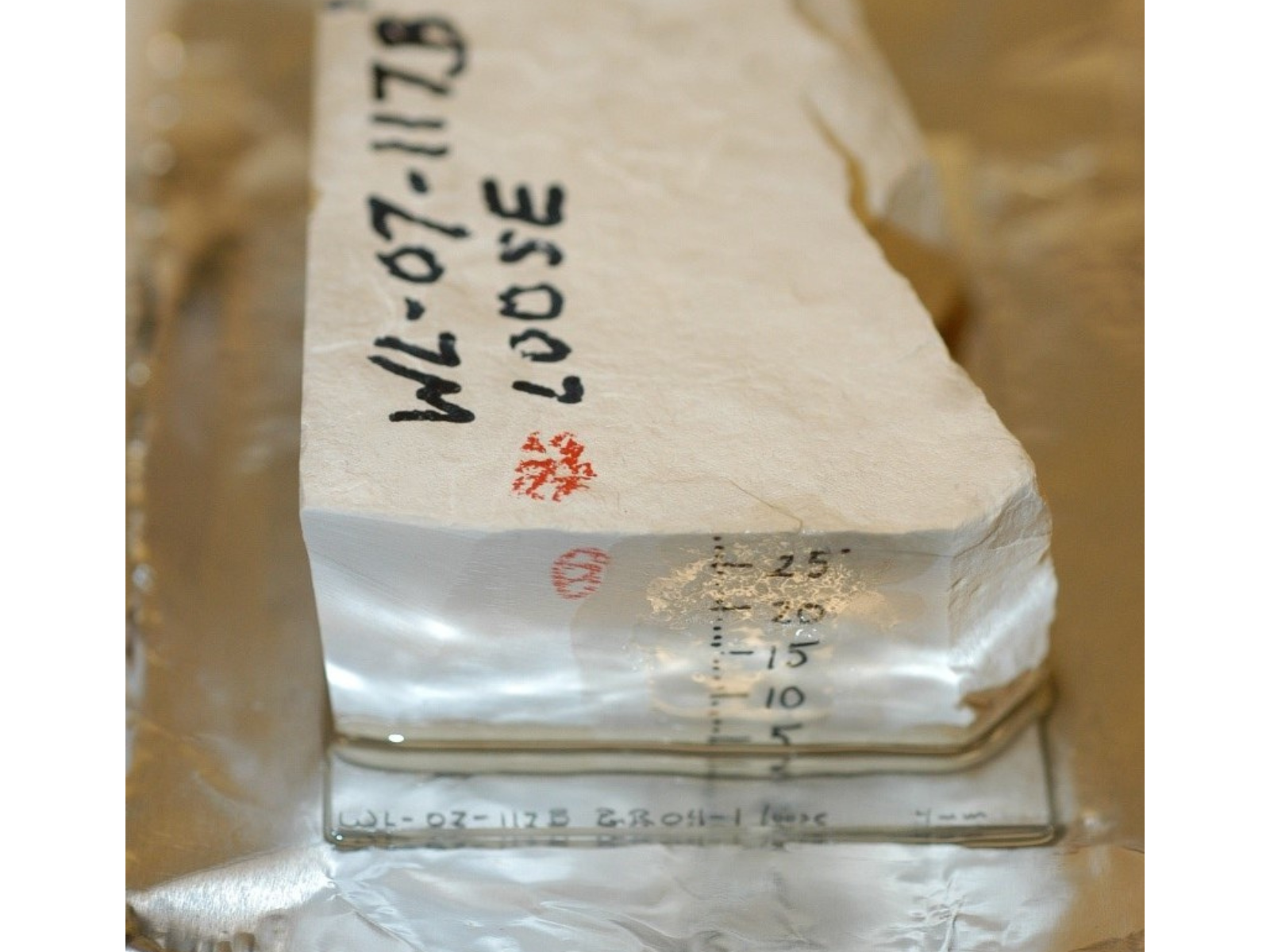

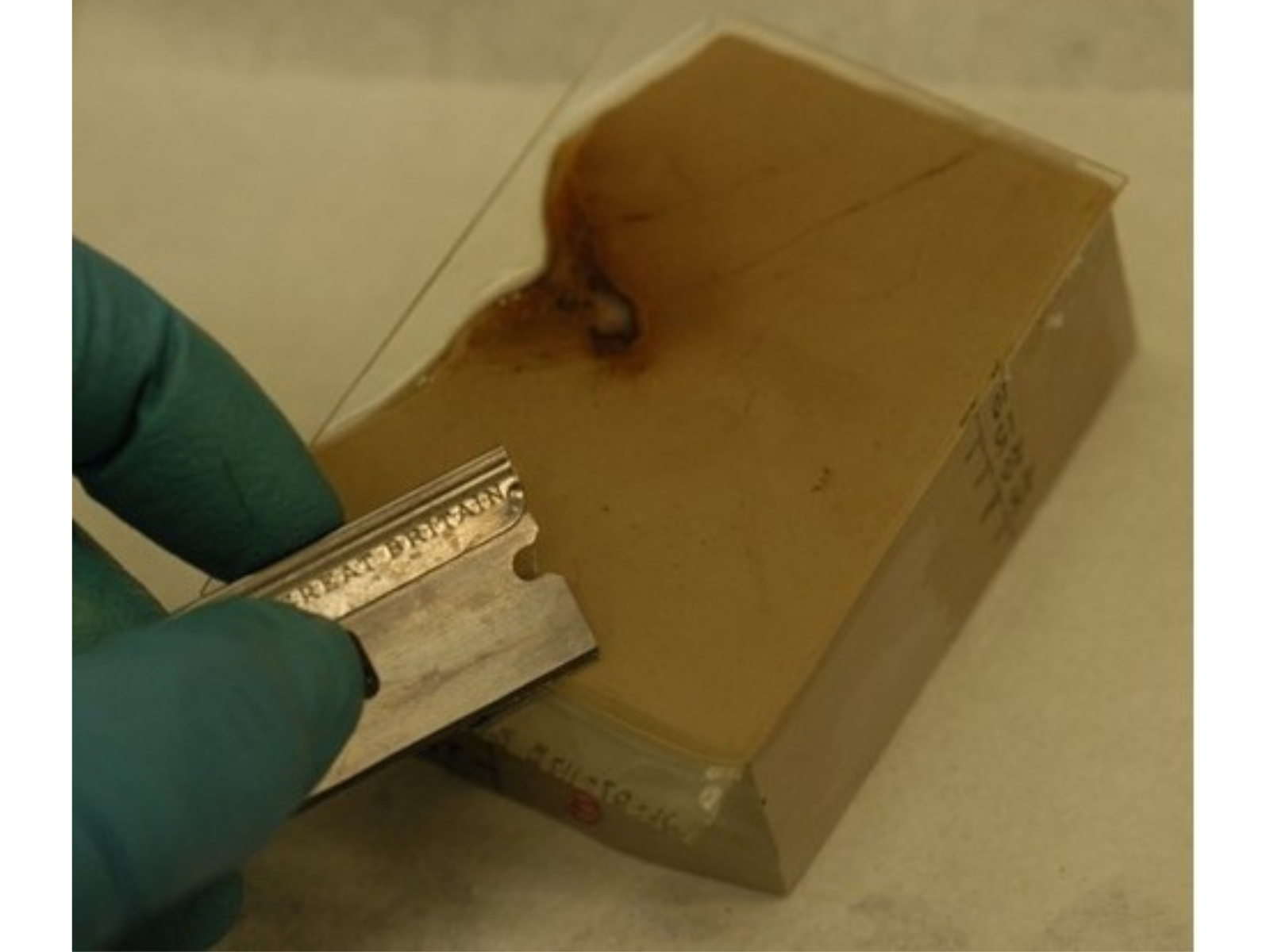

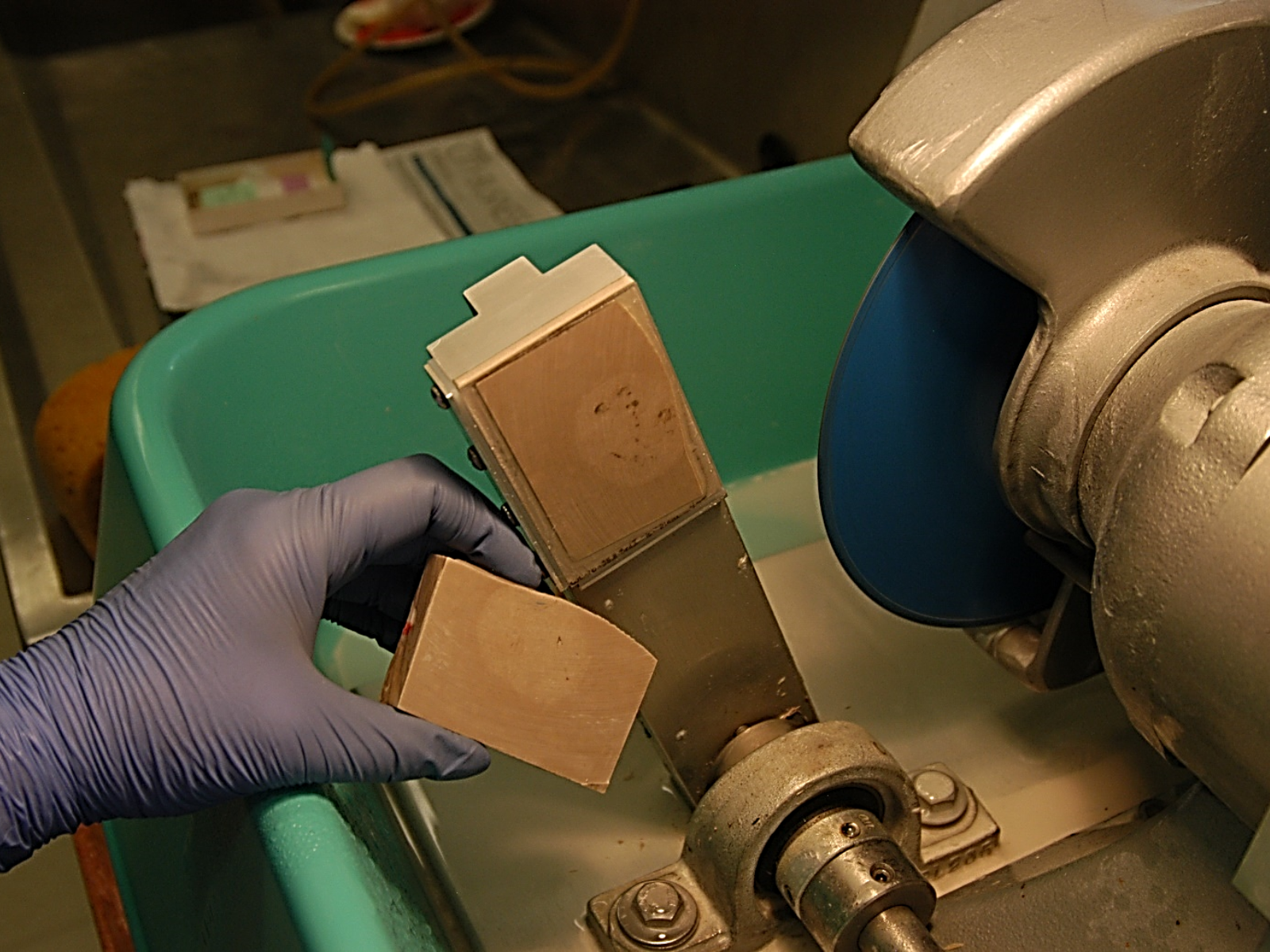

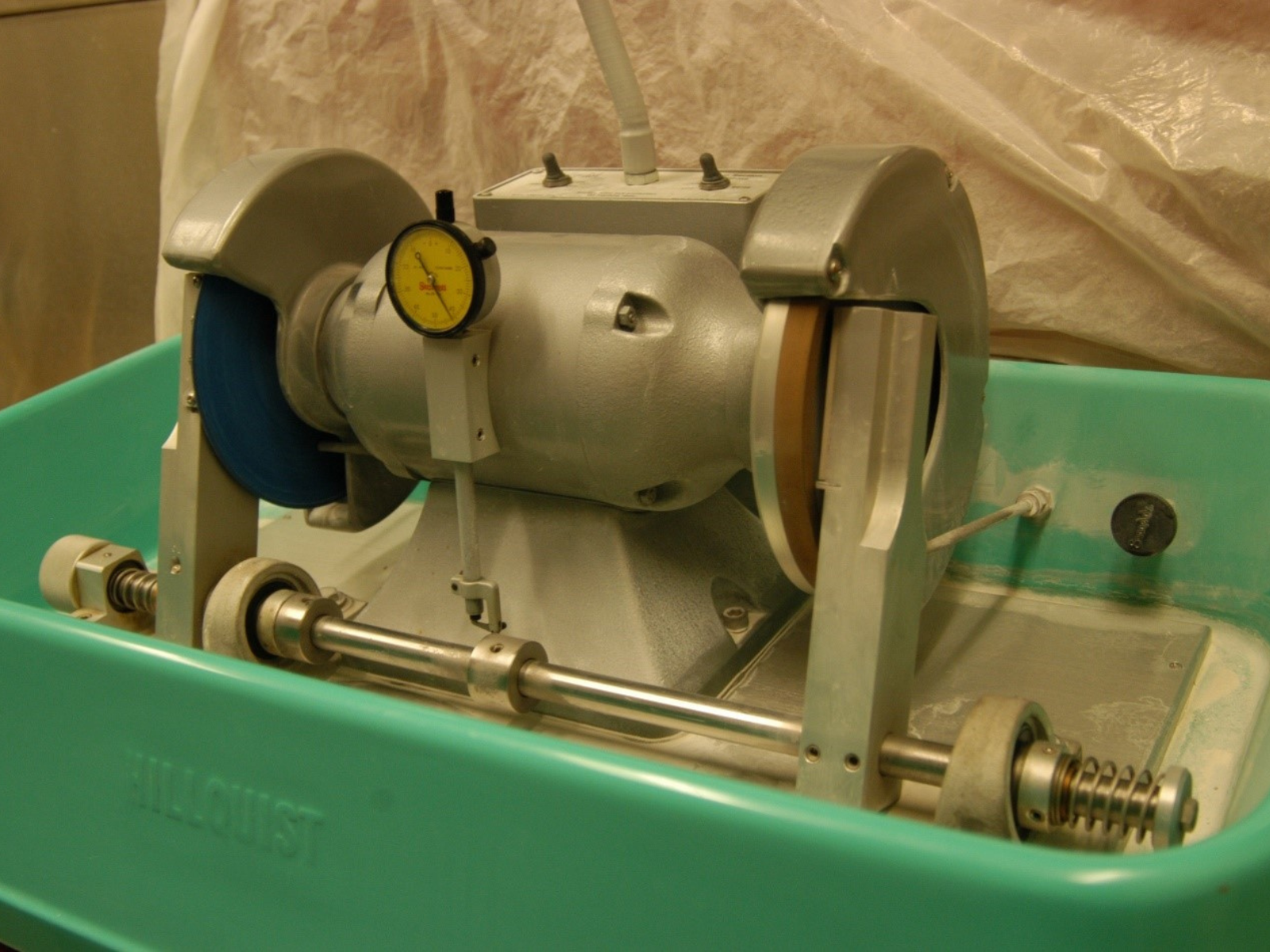

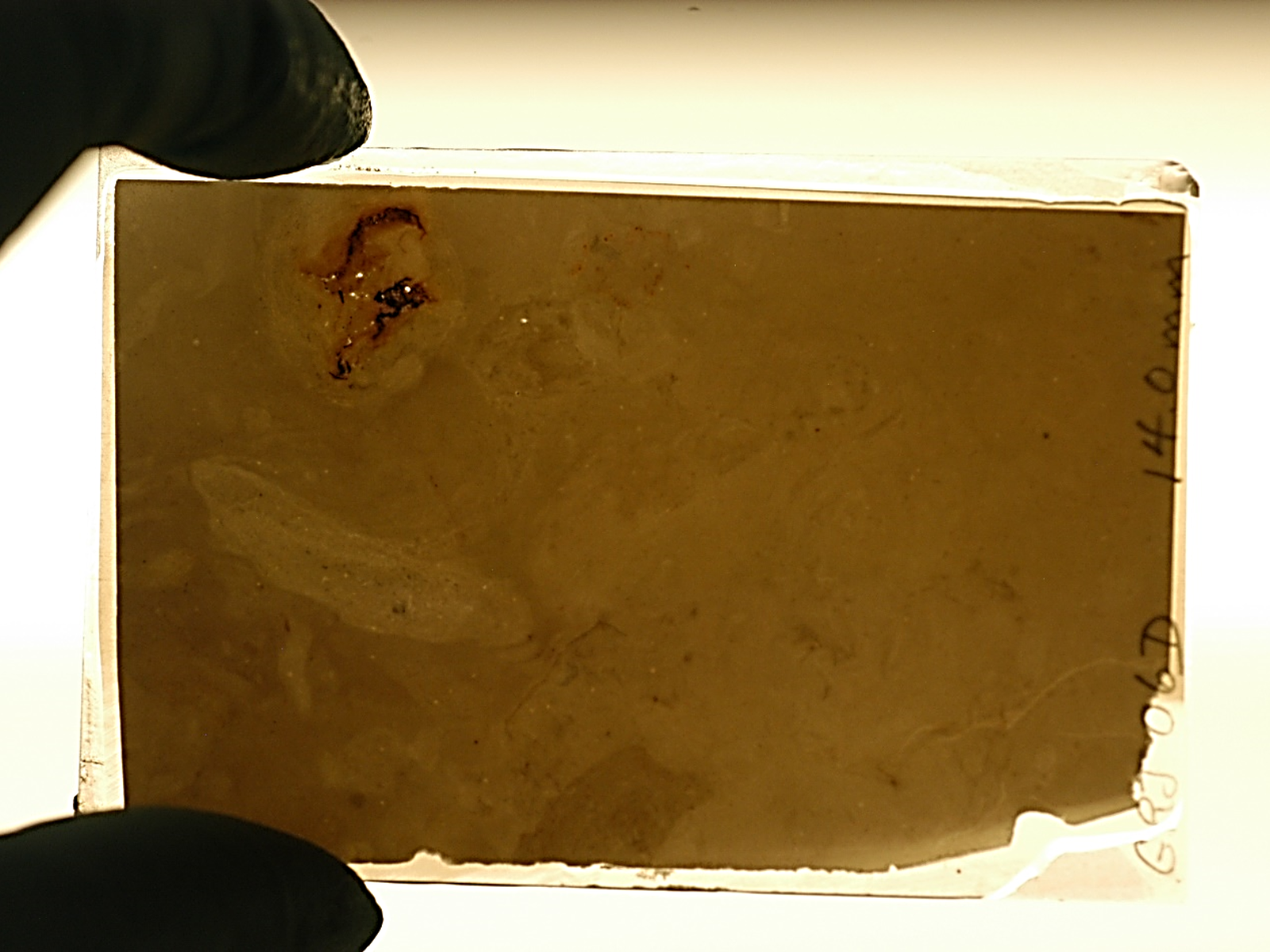

Bone folders, micro spatulas, tacking irons, brass rulers, tweezers, and scalpels are a small list of names of other unique tools that we reach for most often. It’s important that before we perform a conservation treatment on an object in the collection that we ensure the method we choose will be successful, causing no further deterioration then what has already occurred. This means, we really have to think outside of the box, not rush into a treatment, and make sure we have the right tool (wherever that is found) for the job!