Posted on: Tuesday November 28, 2023

A common human trait is to obtain and store our belongings. And, maybe without even thinking, storing them in a relational way that makes sense to us, such as in a sock drawer, or stored together in some logical manner for use, like tools in a toolbox. At the very least, items are stored in a place where we know we can find them when we need them.

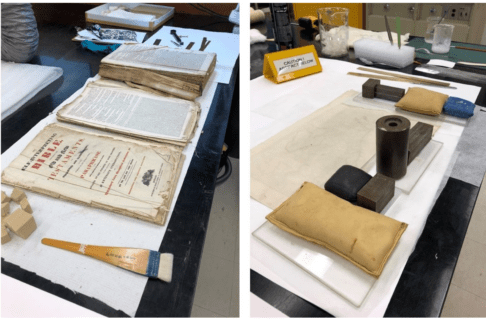

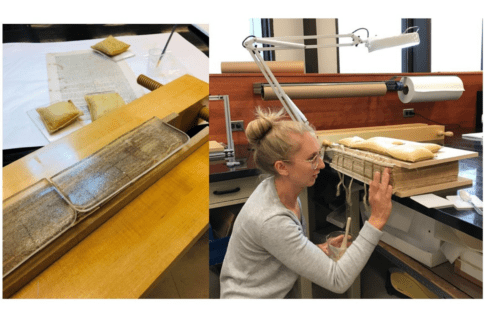

Museums around the world, including here at the Manitoba Museum, have much the same approach when storing their collections. There are over 300,000 specimens in the permanent collections of the Natural Sciences section, of all different types, shapes, and sizes, and they all need to be stored in a systematic way so that we can find them when they are required for research, education, or exhibits.

Lichen specimens are stored in individual trays, and have labels with their catalogue number, identification and data.

In scientific collections, we store specimens of the same species together, and then numerically by their catalogue number. This way, a single particular specimen can be easily located. This is the system that is used most commonly for museum collections including insects, mammals, birds, fossils and plants. Other collections, such as minerals, are stored by their chemical groupings. There are also some specialized research collections that are stored together as an assemblage of different species that were all collected from the same site. This system makes it easier for researchers who want to view and compare all specimens from a particular location. For example, all fossils from a Churchill shoreline, or insects that were pollinating a particular field.

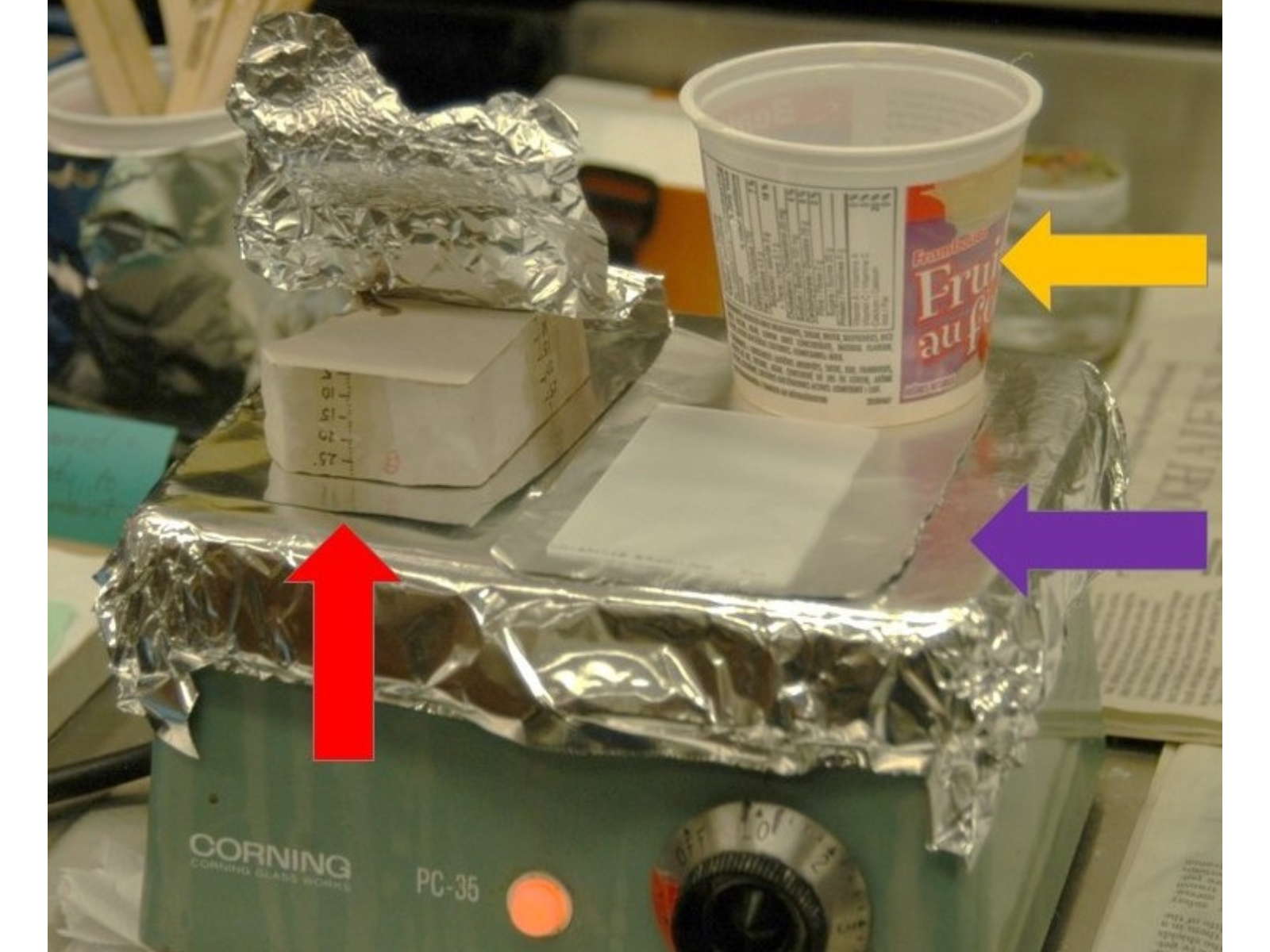

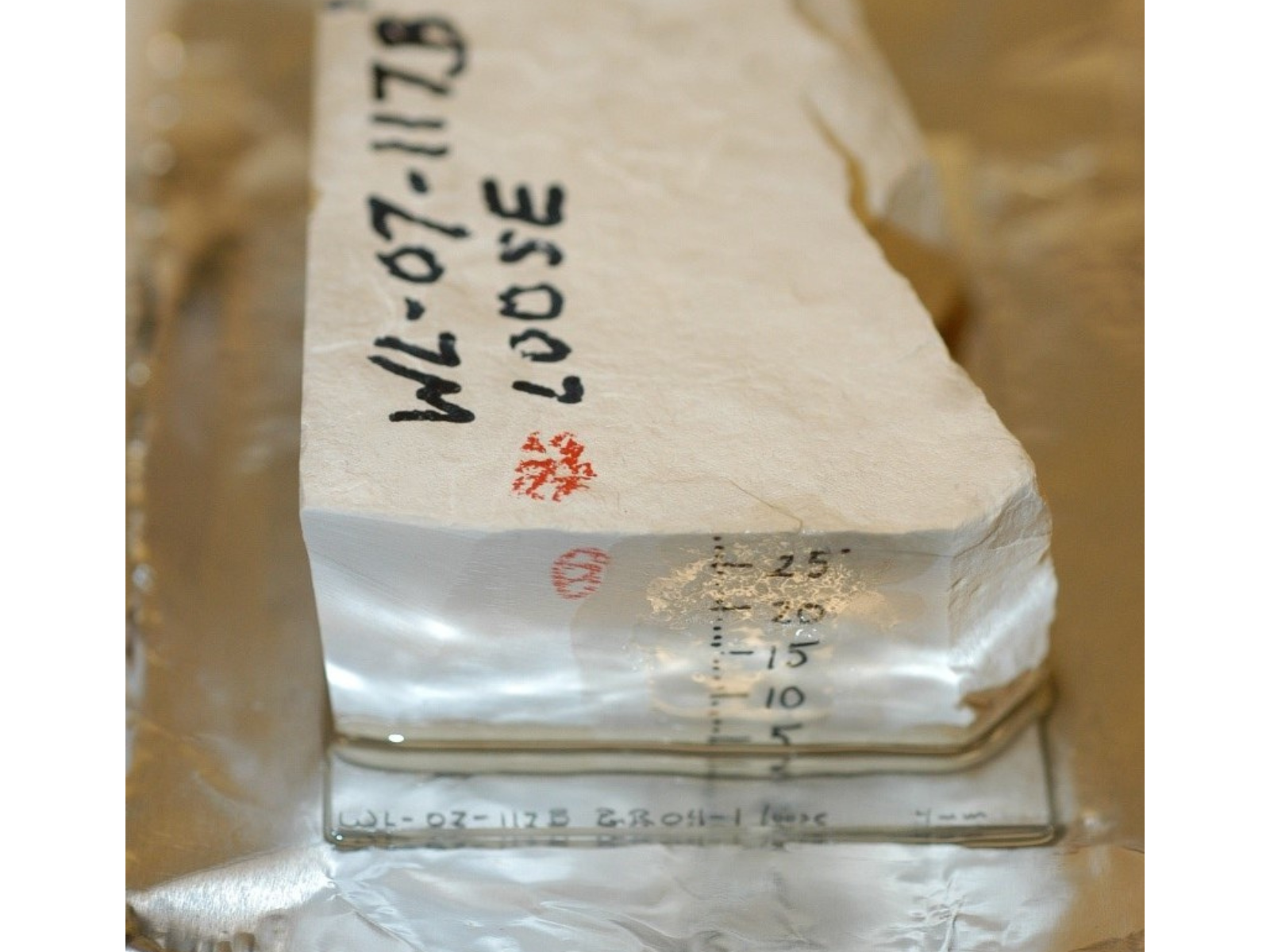

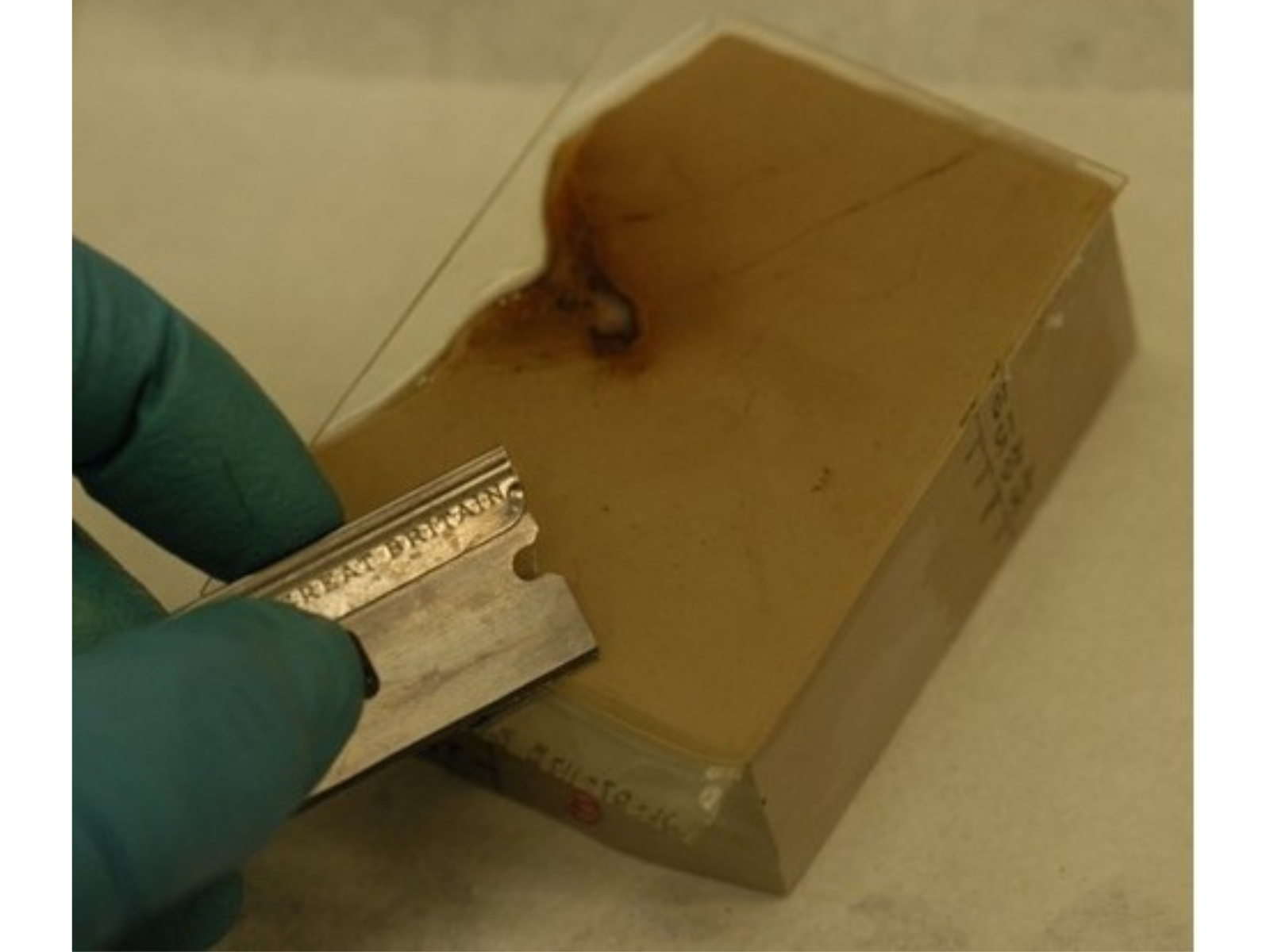

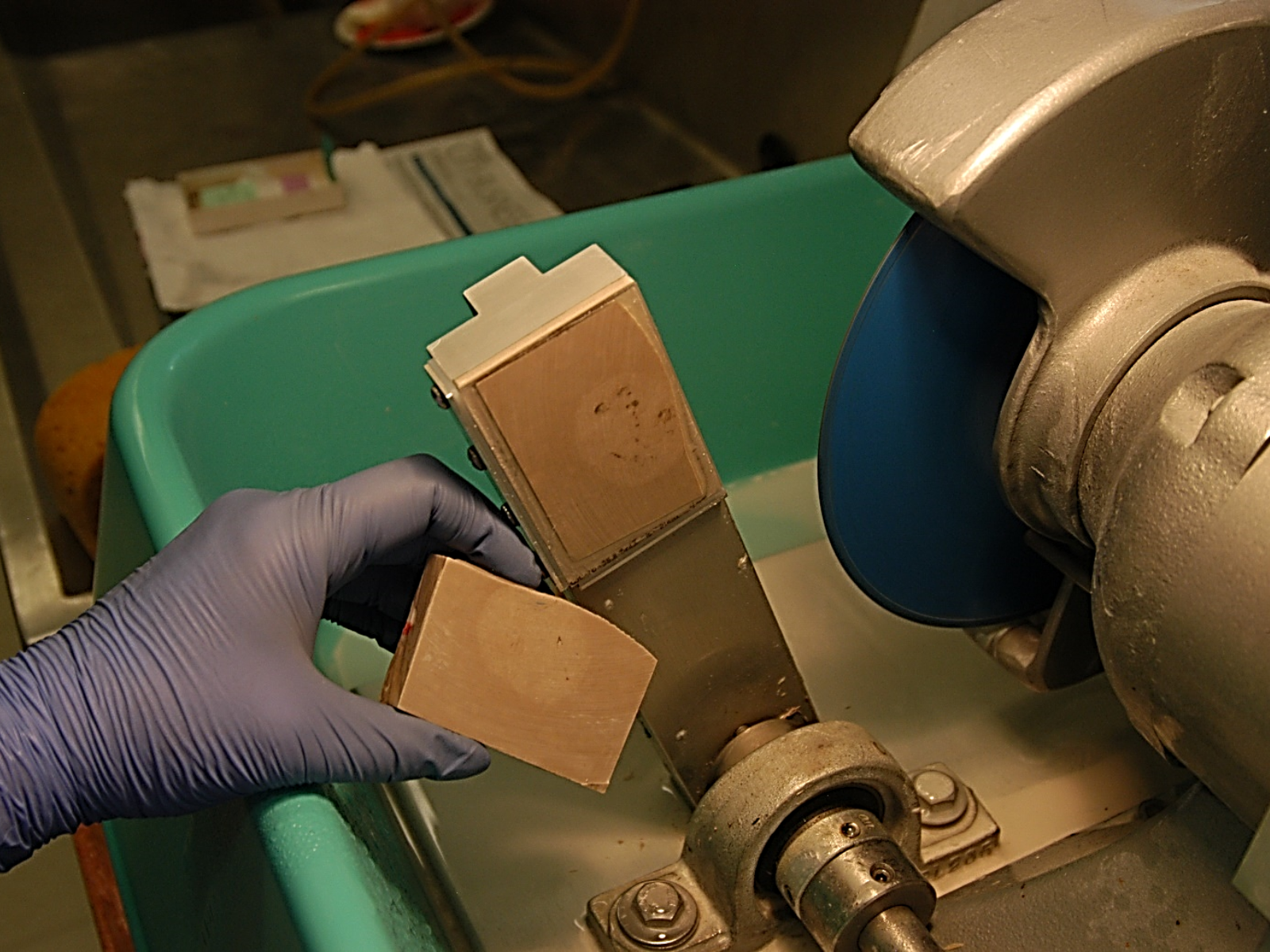

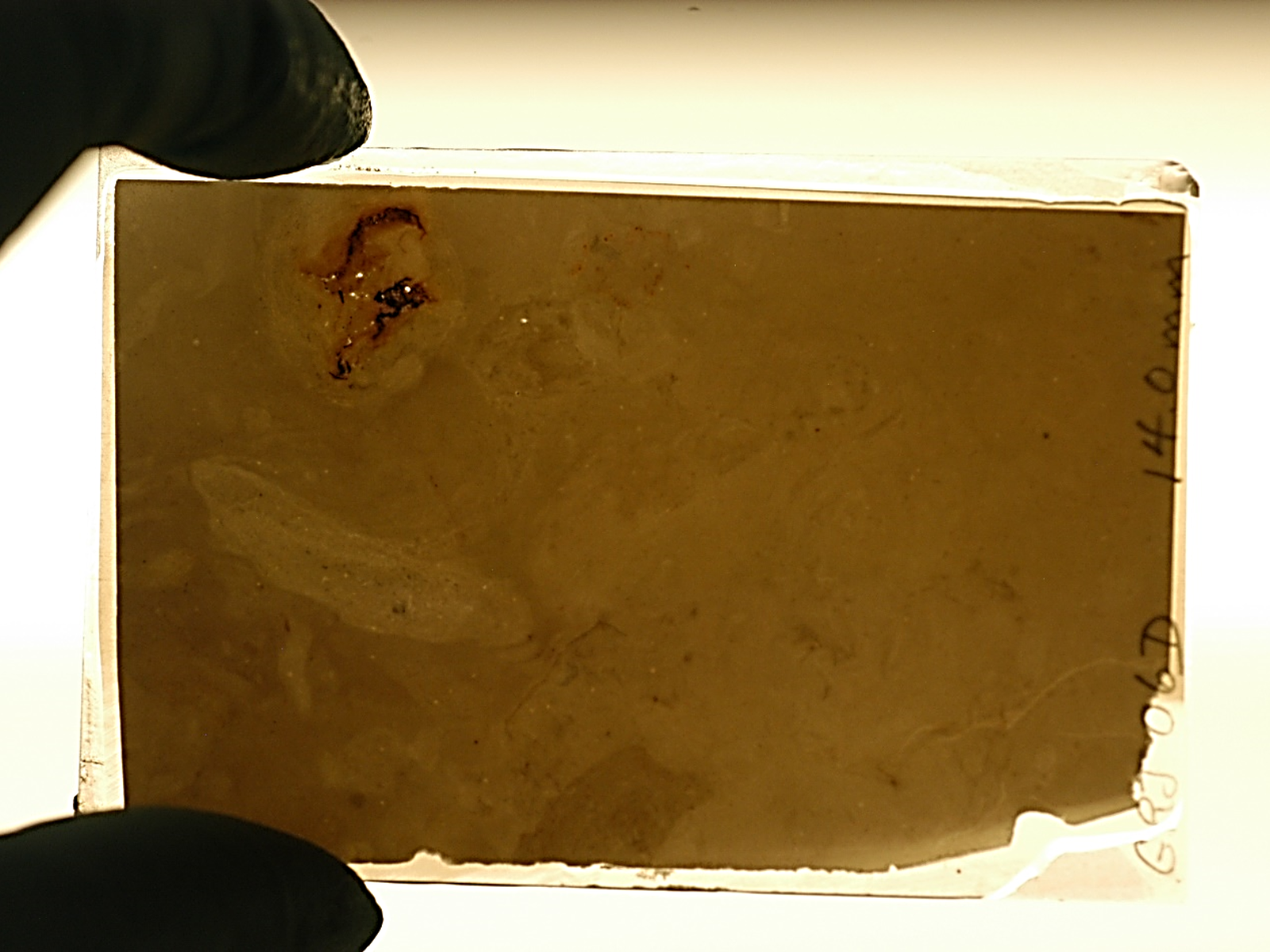

Within each collection, the sizes and storage requirements of the different species vary considerably. They are not all the same size, shape, weight, or fragility level, and we need to be able to provide safe storage solutions in our collections areas for specimens that range from microscopic to very large. For example, paleontological micro-fossils, such as tiny shells or bits of coral, are extremely small (sometimes smaller than 1 mm), and too fragile to even handle individually. In order to keep them safe, but also available for study, they are gently adhered to a special type of microscope slide so that they can be safely handled, and then stored.

Images above: Left – Pinned beetles of the Carabidae Family are stored in special drawers with other specimens of the same species, separated by interior boxes. Right – Micro-fossil shells are adhered to special slides with numbered sections in order to distinguish them.

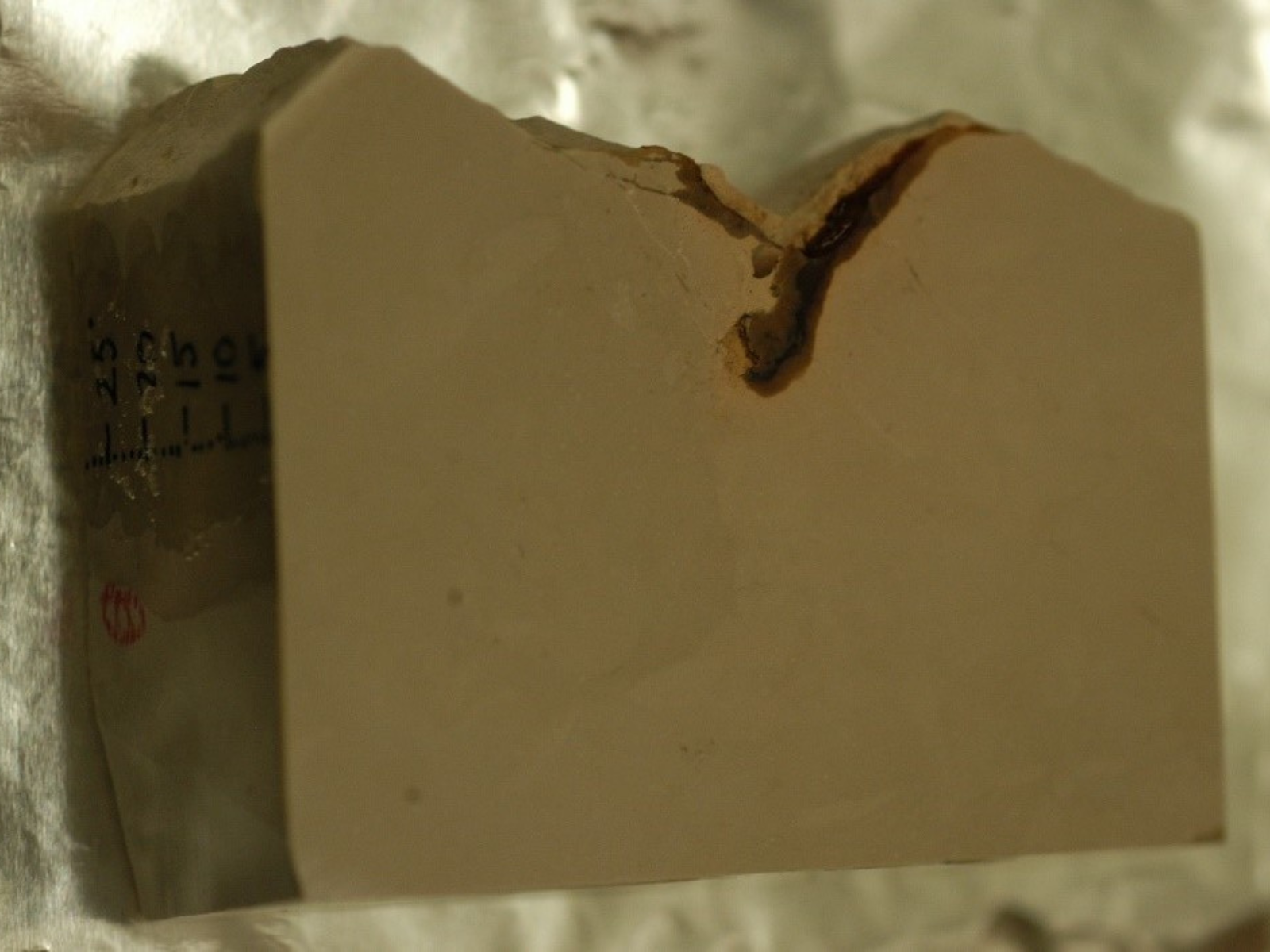

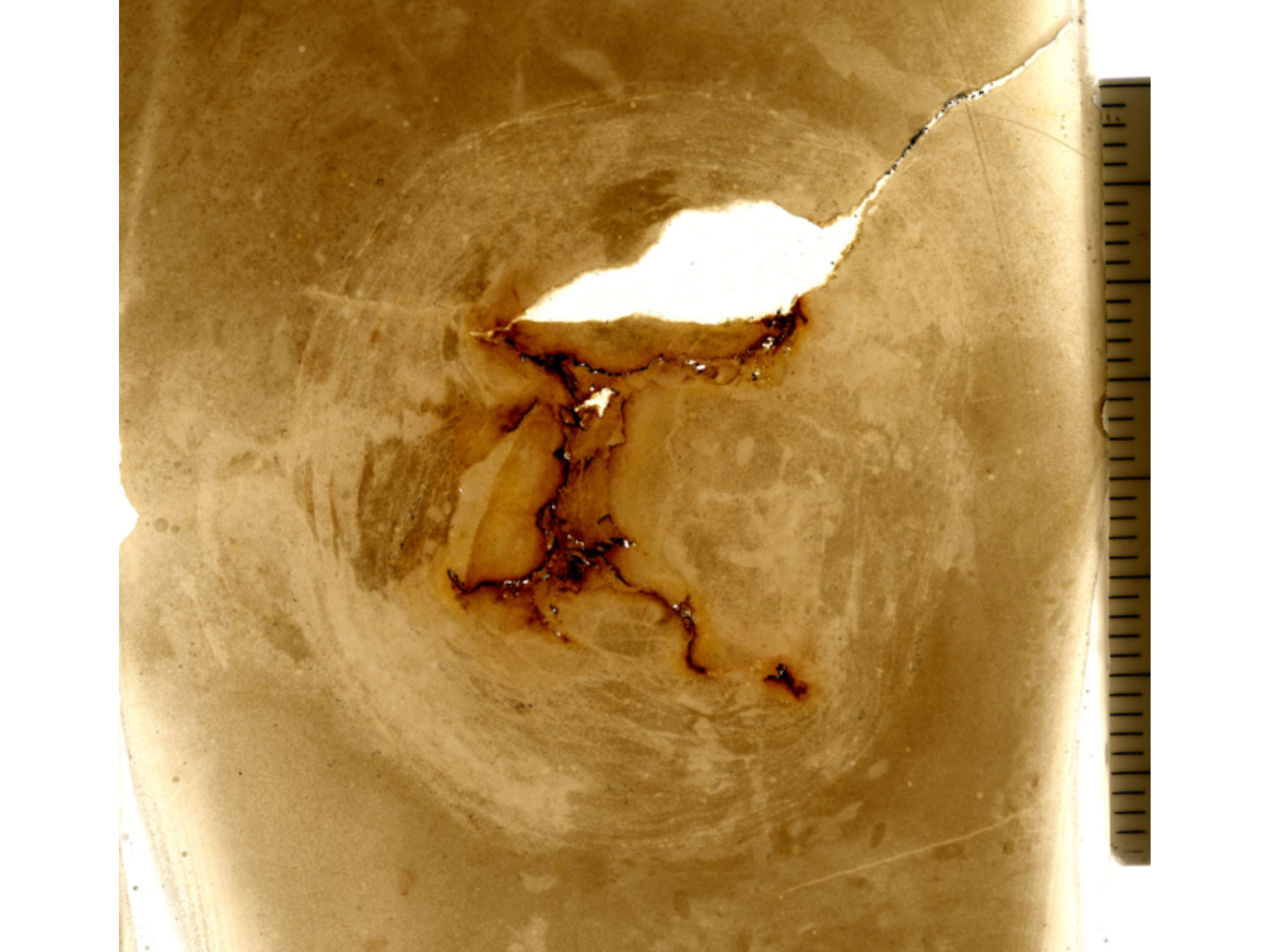

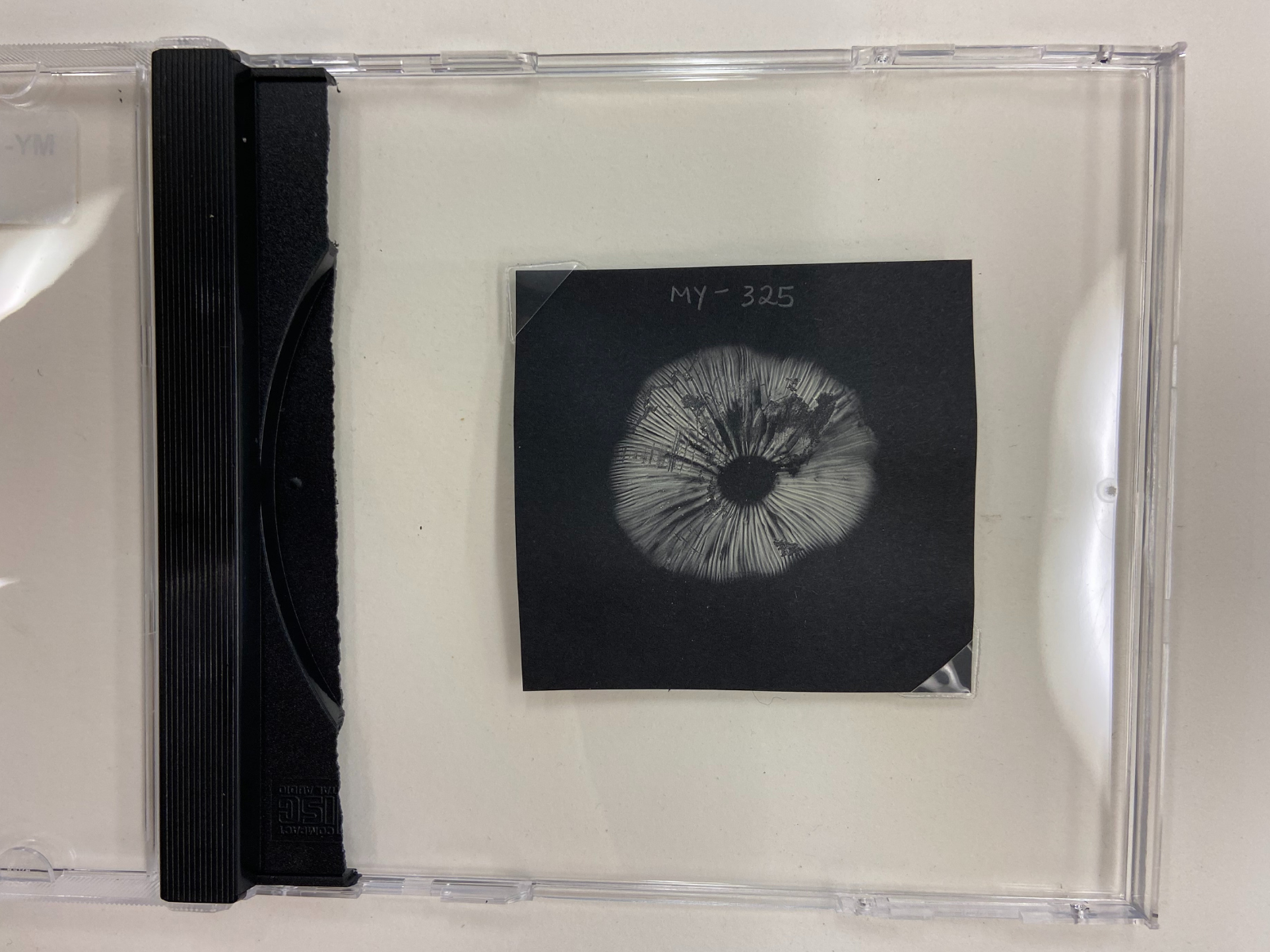

Another type of specimen that we had to devise a storage method for were fungal spore prints. Spores are the tiny microscopic structures that fungi disperse for reproduction and are thus similar in function to plant seeds. The spores are produced on the underside of the spongy or gilled mushroom cap. To assist with identifying the species of mushroom, we collect these spores, and then carefully store them. A spore print is made when mushroom is freshly collected. A piece of black paper is placed under the cap to catch the spores that will be released. The resulting print basically looks like dust in the shape of the mushroom cap. What gives us the information we need to identify them is the colour of the spores – these can be white, cream-coloured, rusty, black or brown. We have found that we can store these fragile paper prints similar to photographs. We place them in plastic CD cases, using photo mounting corners to hold the paper flat; the disk lid closes to protect the print surface from being disturbed.

These cream-coloured spores help scientists identify the species of mushroom that they came from.

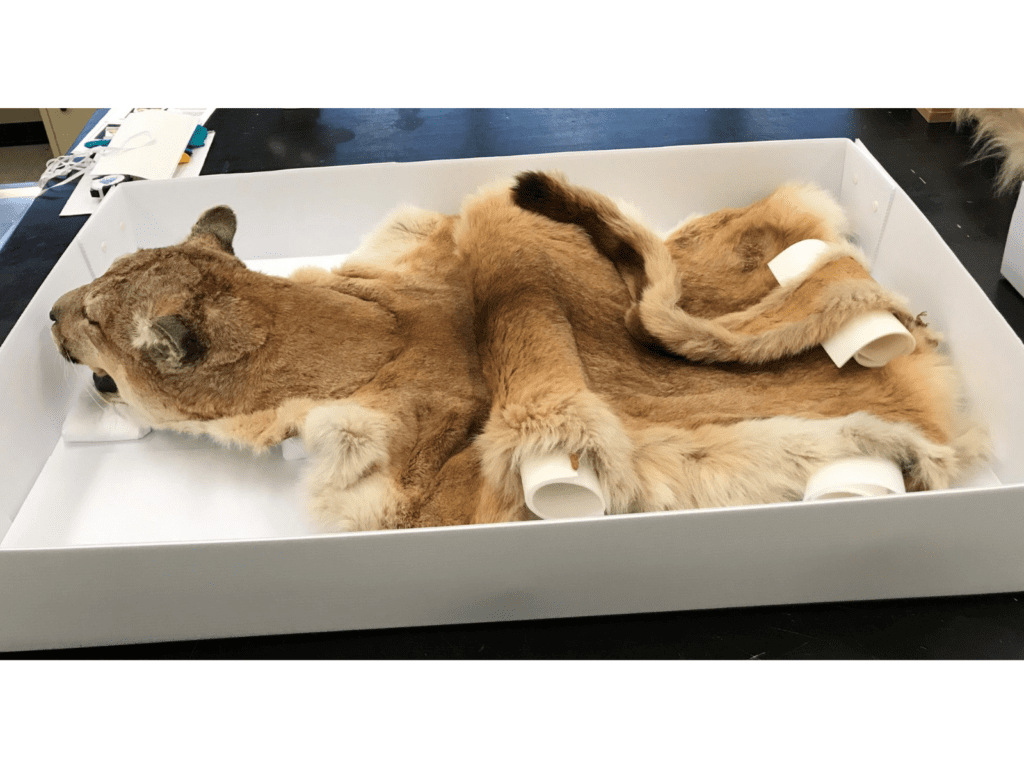

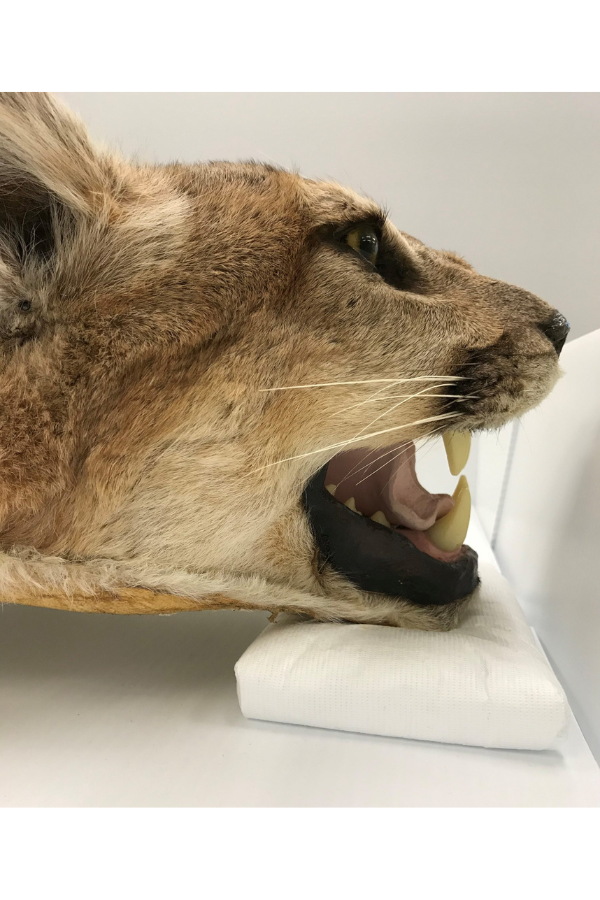

Odd-shaped or very large specimens pose a storage challenge on a whole different level, so we must make special considerations for them. Large mammal mounts, for example, are not easy to store. They are large, heavy, take up a lot of room, and can be fragile too! To add to that list of concern parameters, they can also contain arsenic, which was an effective pesticide used by taxidermists prior to the 1980’s, but is toxic to both pests and humans. We have started to test our collections so we can take the necessary precautions when handling and storing them. Smaller mounts, such as song birds, can be stored in metal cabinets. But larger mounts are a little more difficult, and we have had to develop alternate methods of storing them.

Many of our larger mammal mounts are placed on custom-built wheeled platforms so that they are off the ground, and can be moved if needed. In some cases, we added a wooden framework around the mount so that we can enclose it in poly sheeting, as a barrier for pests and dust. The framework keeps the poly from coming into contact with the fur or feathers of the specimens as it could bend, break, or flatten the structures.

Above: Taxidermied head of a Bison stored on a custom-wheeled dolly for easy transportation. It will be enclosed in protective poly sheeting for storage.

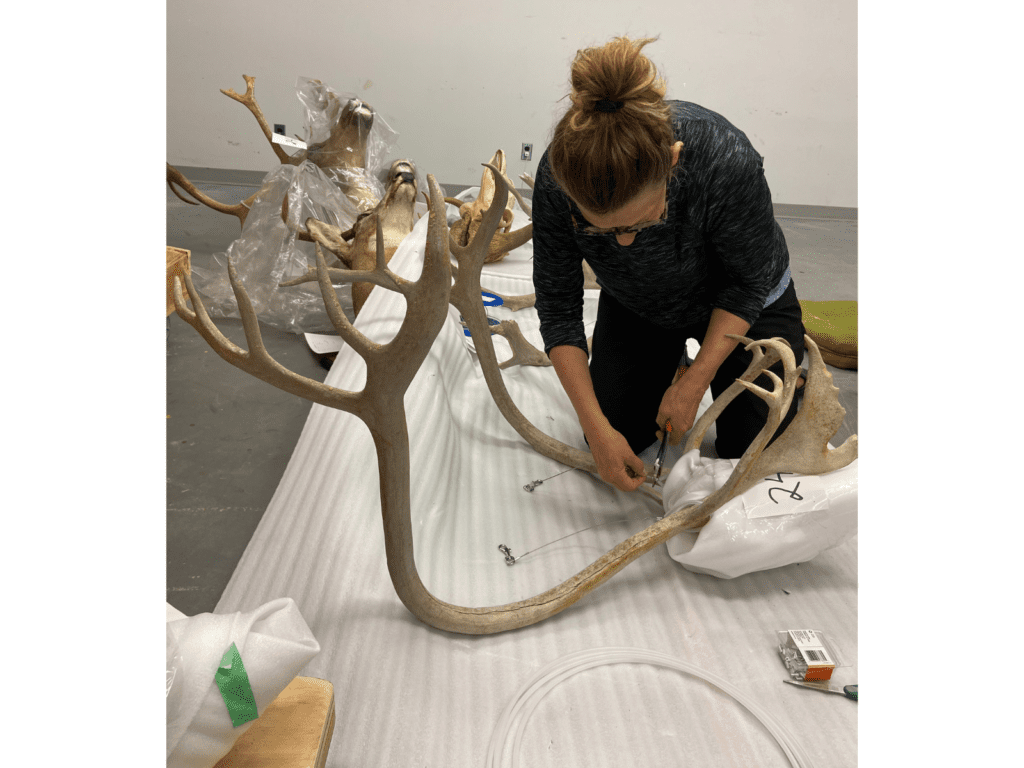

Large mammal skulls, like caribou and elk, can have enormous antlers, and certainly pose another storage challenge. We have adopted a simple and effective storage solution using heavy-duty custom metal frames that are locally fabricated. The frames are spanned with expanded metal centers, and installed where we have open wall space. The large skulls can then be secured and hung on the frame. We are fortunate in that we have large areas of open wall space!

Our next storage challenge is how to store a 25 ft. long whale jaw that weighs 200 lbs!

Strong aircraft cable is used to hang these large skulls with antlers.

Collections Technician, Aro, installing the skulls onto our new metal storage rack.