Posted on: Wednesday June 1, 2011

I recently attended the annual meeting of the Canadian Society of Ecology and Evolution in Banff, Alberta. However, being stuck inside a building on several beautiful sunny days was agonizing and on several occasions I found myself gazing wistfully out the windows at the mountains beyond. Fortunately, visiting other museums while I travel is an important part of my job as it helps me to plan exhibits here at the Manitoba Museum. This trip was no exception and I was able to visit the Banff Park Museum during a long lunch break one day.

The Banff Park Museum in Alberta.

Next to a case of very old birds.

The Banff Park Museum is such an old museum (1903) that the building and its collection were protected as a National Historic Site in 1985. So basically it is a museum of what old museums used to look like. Apparently in the late 1950’s some people in the community wanted the Museum torn down and replaced with a new building and more modern exhibits. Looking around at the beautifully crafted wooden cases, hundred-year old specimens and gorgeous Douglas Fir wood panelling on the ceilings, I was thankful that cooler heads prevailed.

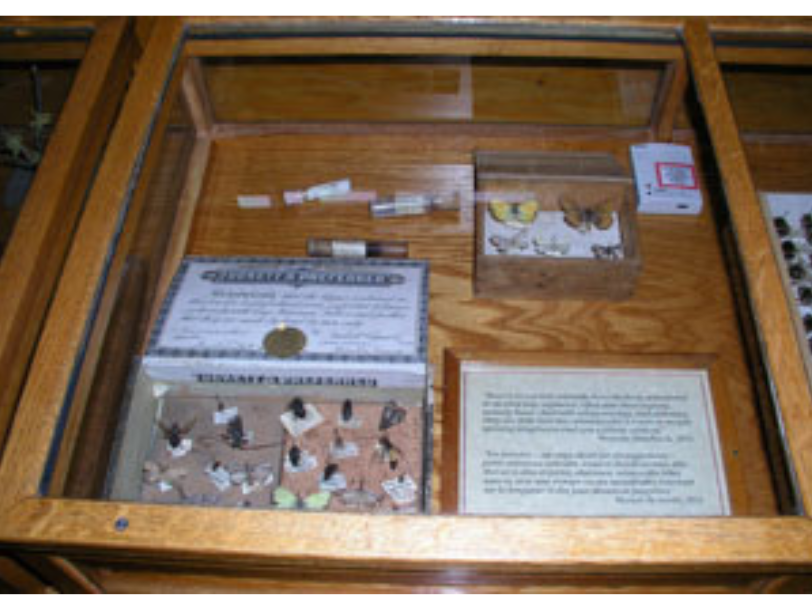

The Museum contains numerous “cabinets of curiosity”, as they used to be called. These cabinets contain more than 5,000 mounted birds, mammals, insects, plants and eggs collected in western Canada mainly between 1890 and 1930. Some of the “newer” exhibits created in 1914, displayed animals in their habitat, an approach that was considered radical at the time. Eventually this approach evolved into our modern-day dioramas. Nowadays some Museums are tearing down their dioramas and putting in “cabinets of curiosities” again, albeit with a modern twist. So I guess that “what goes around comes around” even in Museum design. I myself tend to think that what is most desirable is a mixture of the best of both, especially when many dioramas themselves have become worthy of preservation.

A “radical” new diorama circa 1914.

The Curator left and never came back.

The Banff Park Museum is a museum of a museum in yet another way-there has not been a Curator there since 1932 when the last one retired. What this means is that the collection has effectively “died”. Curators keep collections alive through research, promotion and interpretation. Collections that cease to grow cannot incorporate new, valuable information about genetic, population and ecosystem changes over time. Without this information, our societal ability to make wise decisions about resource use is hindered. Curators ensure that information from the collections is accurate and promote collections use by anyone who needs it, such as scientists, managers, and government employees. Curators are also able to interpret the collection in the context of our current society. Unfortunately the important supporting role that collections play in science is rarely understood or appreciated, even by some scientists.

Image: An orchid on display at the Museum.

I was reading the job description of the ideal Curator in the Museum’s interpretive brochure. Professor John Macoun suggested in an 1895 correspondence that the ideal Curator should possess the following qualifications:

- “A man of wide intelligence;

- Energetic (not a hotel lounger);

- Ought to be able to skin a bird or mammal;

- Will talk natural history, mineralogy, geology or anything else to the visitor, and

- A political bloke should be the last man for that place.”

What’s amusing is that a natural history Curators’ job description hasn’t really changed in a hundred years! You still need to be energetic to conduct field work and collect specimens. You still need to know how to prepare specimens for preservation. You still have to have a broad interest in natural history and the ability to communicate with visitors. And we are most definitely NOT “political blokes”. Really the only thing that has changed is the technology that modern Curators employ. I use a palm pilot to record my field notes instead of a notebook, a GPS to navigate instead of a map and compass, and a blog page to “talk natural history” with the visitor. It seems that “the more things change the more they stay the same”.

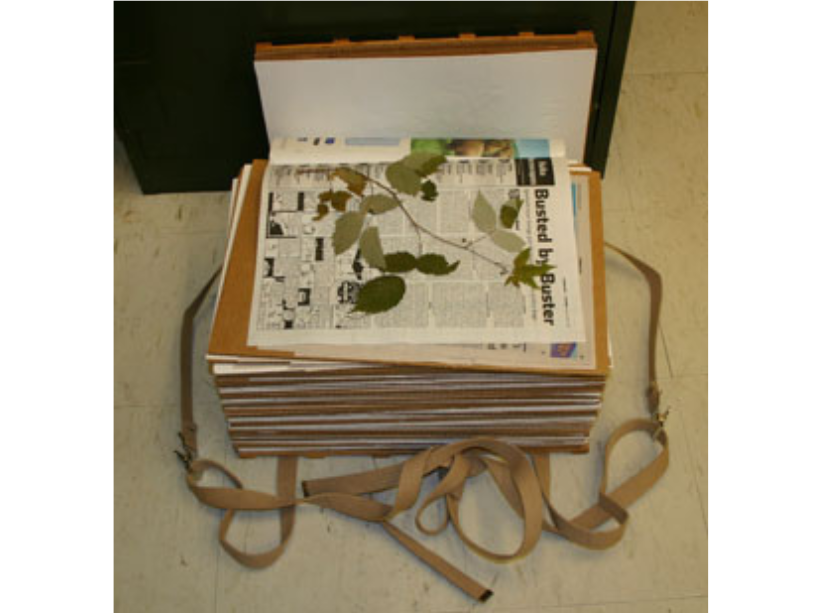

Image: Museum display of pinned insects.