Posted on: Monday March 31, 2014

By Dr. Graham Young, past Curator of Palaeontology & Geology

Recently, there seem to have been a lot of stories in the media about the remarkable intelligence of elephants. Scarcely a week goes by without a new science story about how elephants are among the few non-human creatures that are self-aware, about their superb communication skills, about the ways in which they care for one another, or about their wonderful memories (it is true: an elephant never forgets). Whenever I see these stories I feel wistful, contemplating the elephants that used to live around here. I imagine how they wandered across the landscape, using their big brains as they communicated about food and predators.

If you are here in still-snowy Winnipeg, you might wonder if I am feeling OK, or you would at least think “what does this have to do with our local situation?” After all, wild elephants live a very long way away, in warm parts of Africa and Asia. Our lack of living elephants is, however, a disparity of time rather than one of geography. Geologically speaking, it is just the blink of an eye since the time when this area was regularly visited by herds of elephants.

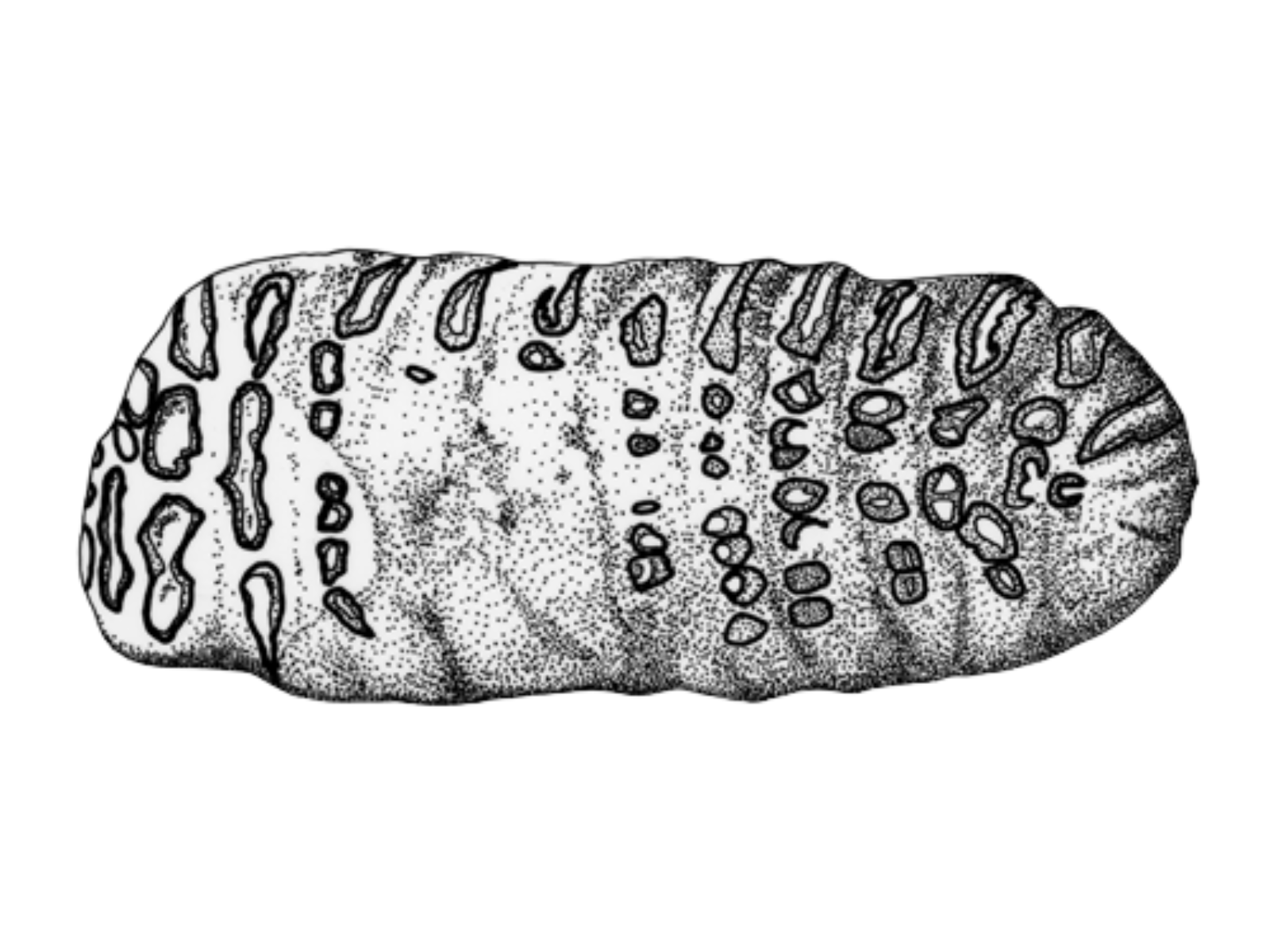

Crown view of a woolly mammoth molar from Bird, northern Manitoba (specimen V-1739; illustration by Debbie Thompson)

Partial mammoth pelvis from southeastern Manitoba (specimen V-2640; scale is in centimetres and inches).

Side view of a mammoth molar from southeastern Manitoba (specimen V-2554; scale is in centimetres).

I am speaking, of course, about mammoths. Although woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius) are better-known from Ice Age (Pleistocene) deposits in Siberia, Alaska, and the Yukon, many examples have been found across the Canadian Prairies. Quite a few mammoth bones and teeth have been collected in Manitoba, along with the occasional tooth belonging to their distant cousin the American mastodon (Mammut americanum).

Here at the Museum we have mammoth teeth, vertebrae, limb bones, jaws, and other pieces, collected from many different sites in Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Nearly all of these have been found separately in glacial deposits, and there is good evidence that they had been transported and abraded before they were finally deposited. Most of them are not mineralized; they are composed of the original bone and tooth material that was preserved in sand and gravel far below the water table. Some of the bones were still so “fresh” that they stank of rotting mammoth when we started to dry them out for preservation.

Sadly we have not yet found any more complete skeletons, but the fossils we have give excellent evidence that these animals were widespread in this region. They were probably common during the interglacial warm spells, those intervals of milder conditions when the ice sheets receded from this region.

Image: An incomplete mammoth tusk found northeast of Transcona (Winnipeg), Manitoba (specimen V-209).

Some of our mammoth bones are from sites where associated wood material has been dated to about 40,000 years old, so they date from well before the end of the Ice Age. The last mammoths in North America, however, became extinct about 10,000 years ago, and the very last ones in the world lived on Wrangel Island, Siberia, until just 4,000 years ago (by which time the Egyptians had already constructed some of their pyramids!). We don’t really know why mammoths became extinct, but there seem to have been several factors involved: climate change at the end of the Ice Age and increased hunting by human populations may have been the major causes.

Since the mammoth is often reconstructed as a hairy creature with a “primordial” sort of appearance, you might think that it was not really that similar to modern elephants, but modern scientific information tells us otherwise. We have long known that the teeth and bones of mammoths indicate an affinity to Asian elephants (genus Elephas). Asian elephant teeth, for instance, are much more like mammoth teeth than they are like the distinctive teeth of African elephants (genus Loxodonta). Recently, genetic studies have confirmed the similarity and shared ancestry of mammoths and Asian elephants. Mammoths and Asian elephants shared an ancestor about 5.8-7.8 million years ago, while that shared ancestor diverged from African elephants 6.6-8.8 million years ago.

Image: A mammoth scapula (shoulder blade) from southeastern Manitoba (V-2639).

Many of the new things we are learning about elephant behaviour seem to apply to both Asian and African elephants. Given what we now know about evolutionary relationships, it must be assumed that mammoths would have had the same sort of intelligence and behavioural traits, and it is possible that even mastodons were somewhat similar. The new information on elephant intelligence is allowing mammoths to be well understood as “living” creatures, even if the attempts to clone them are unsuccessful.

It is saddening that we came so very close, geologically, to seeing those herds of mammoths. Whenever I look at those fossils, whenever I contemplate the tusk of a huge adult or the jaw of a baby mammoth, I miss the animals.

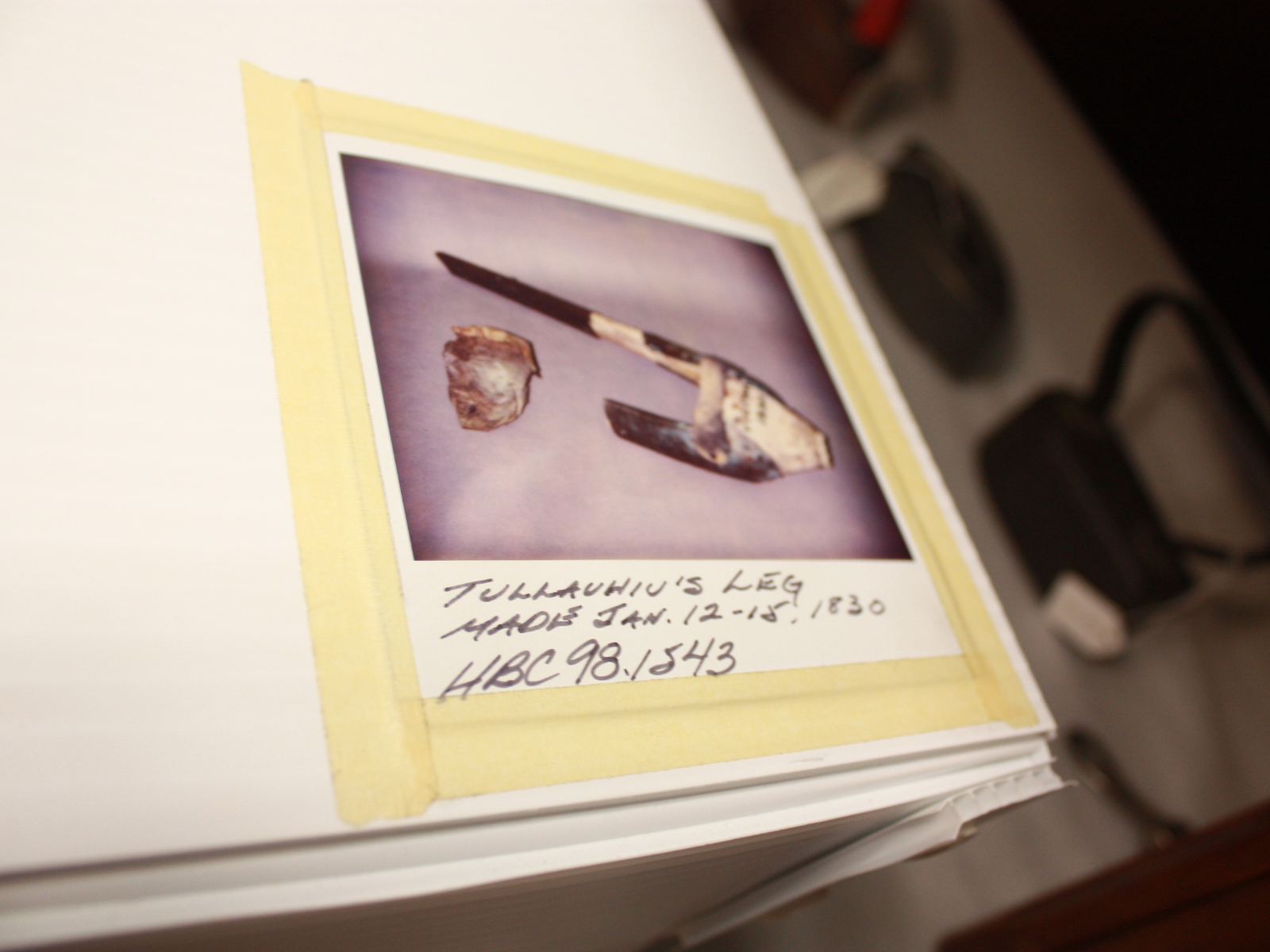

![A clip of a journal entry reading, "Not to name mere instances, we found the aged [indecernable] drawn on a sledge by his companions, when the old man above alluded to was suffered to walk as best he could : as was equally the case with Tullauhiu, whom we supplied with a wooden leg to replace his loss."](https://manitobamuseum.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/MM_HBC-John-Ross-journal-4x3-1.png)