Posted on: Friday August 8, 2014

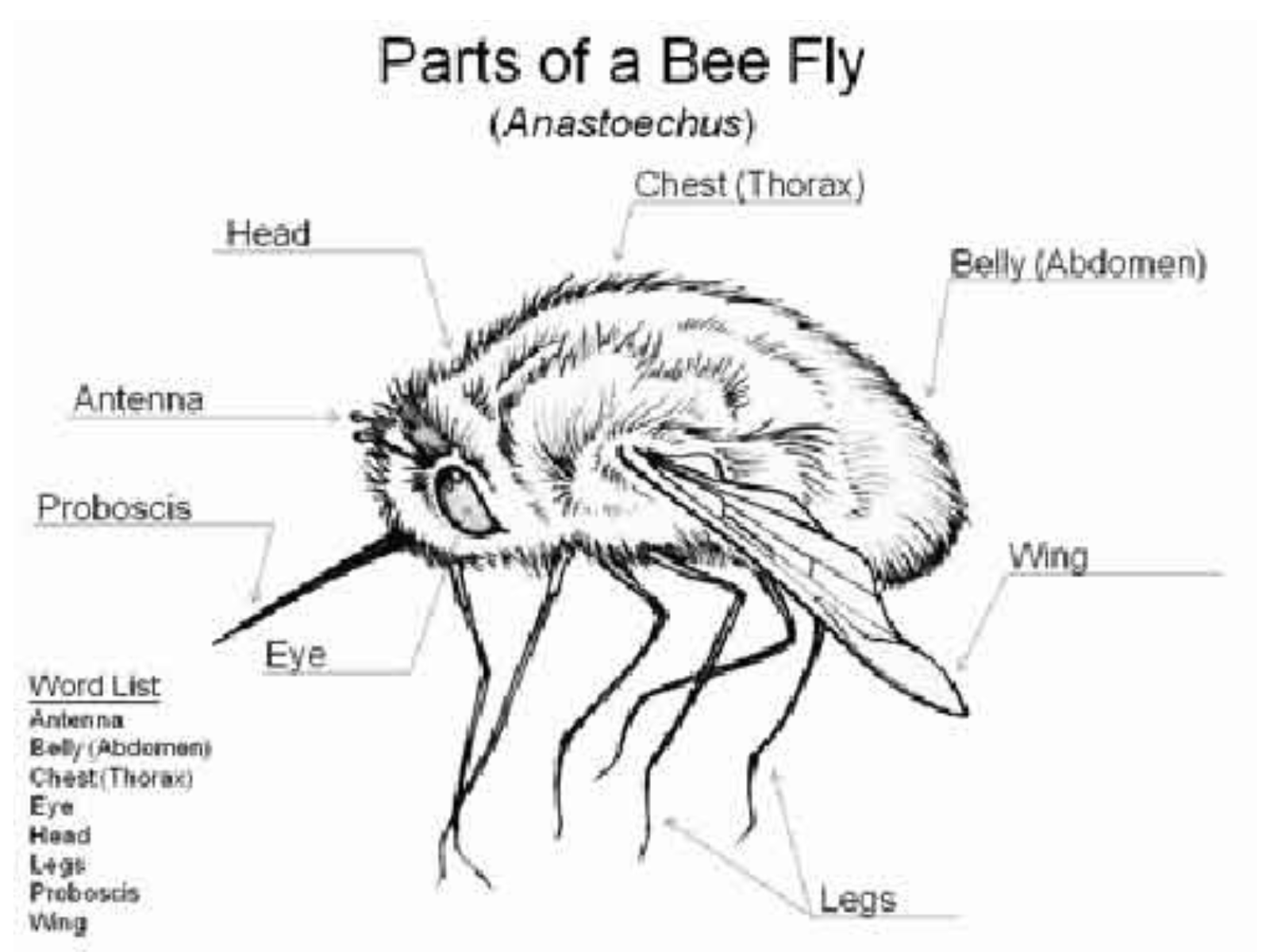

Last year I was able to attend a moss identification workshop given by Dr. Richard Caners. I had largely been ignoring the mosses because it is really hard to be good, all-around naturalist these days. My specialty is vascular plants. When I first started working here at the Museum, I had to learn how to identify fungi and lichens. Then I had to learn how to identify pollinators for my research (and trust me that’s not easy!). This year though I’m determined to collect and identify some mosses for an upcoming exhibit.

This July I spent several days hiking through the forests and rocky outcrops in Whiteshell Provincial Park. Although you’d think rocks would be devoid of life, there are all sorts of creatures making themselves at home on the granite outcrops out there. First the lichens show up, forming a thin crusty, coating. Then in the small cracks where there is a little bit more moisture, the mosses show up. Flowering plants like blueberries (which I thoroughly enjoyed eating!) then germinate in the moist, tiny pockets of soil that the lichens and mosses have created.

Lichens and mosses are the first organisms to colonize bare rock.

Flowering plants colonize cracks in the rock where mosses grow.

Part of the reason why mosses are so small is because they lack true vascular tissue (i.e. long, thin straws that help tall trees suck up water). Plants that lack vascular tissues cannot move water as far, restricting their size. Although mosses can’t transport water long distances, they can absorb water very quickly. The most absorbent mosses can suck up 10 to 20 times their dry body weight in water, often within only a few minutes time. Sphagnum is particularly absorbent and was used for bandages in Europe during World War I to save cotton. The antiseptic properties of the moss were also beneficial in preventing infection. Peat moss is still used extensively in the horticulture industry as potting soil and to create industrial chemicals. Peat is also used to create the well known libation-scotch!

Image: Sphagnum mosses absorb lots of water very quickly.

Instead of flowers, mosses produce tiny capsules that contain millions of spores. Some of these capsules explode, flinging the spores away from the parent plant; wind helps to disperse them further away. When I’m in the field looking at these unusual ecosystems I find myself wondering what it would look like if I were an insect. Suddenly these tiny plants would be huge trees with massive spiky leaves. Their intricate flying spores would be dangerous projectiles. Among the mosses there would be a stunning diversity of minute insects and bizarre animals like water bears, rotifers, and velvet worms. It would be like getting sucked into a Dr. Seuss book!

So if you’re planning on going hiking in the woods this summer, take a moment to look closely at the moss forests that you’ve probably never noticed before.

Moss capsules are full of millions of tiny spores.

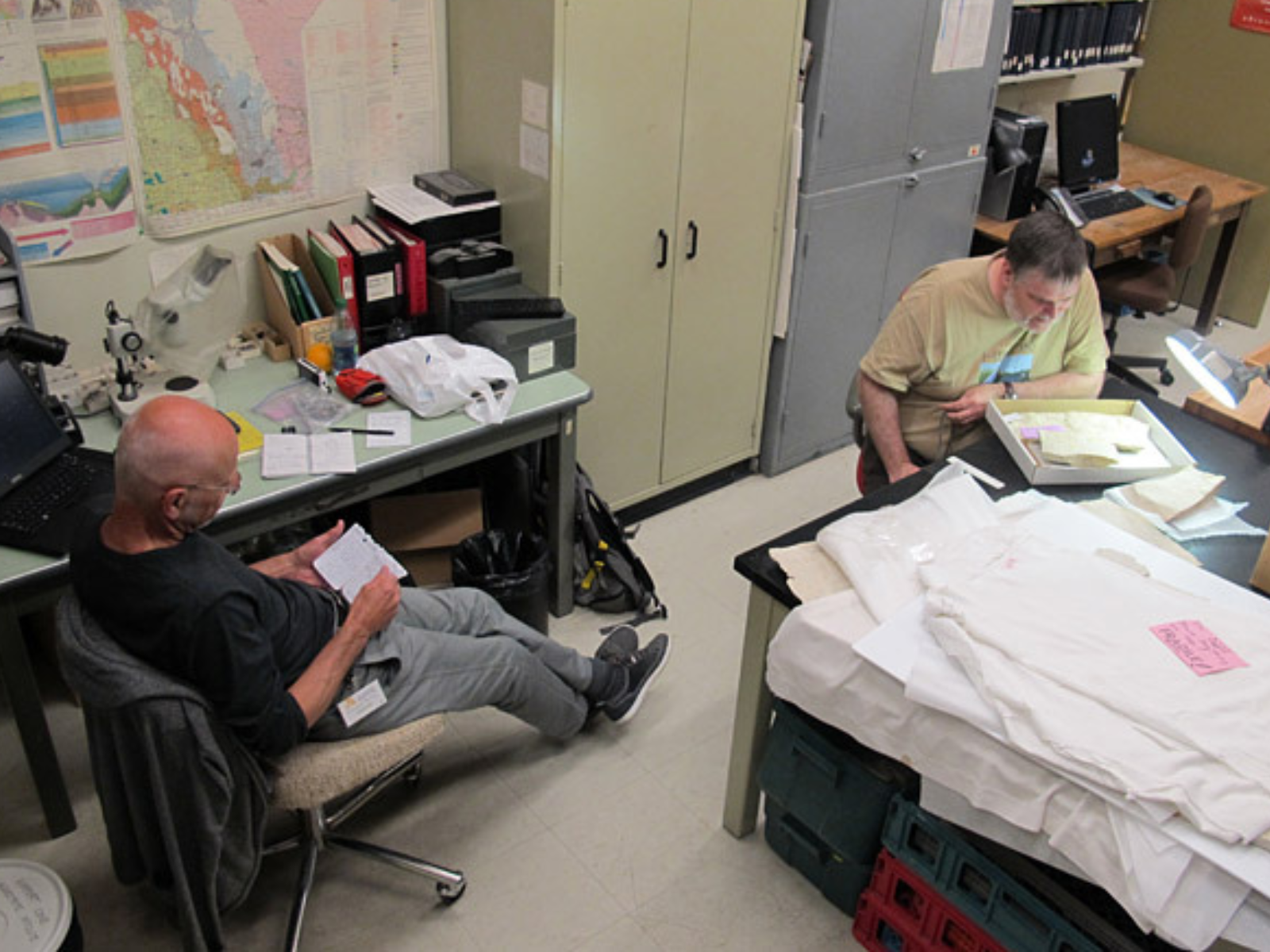

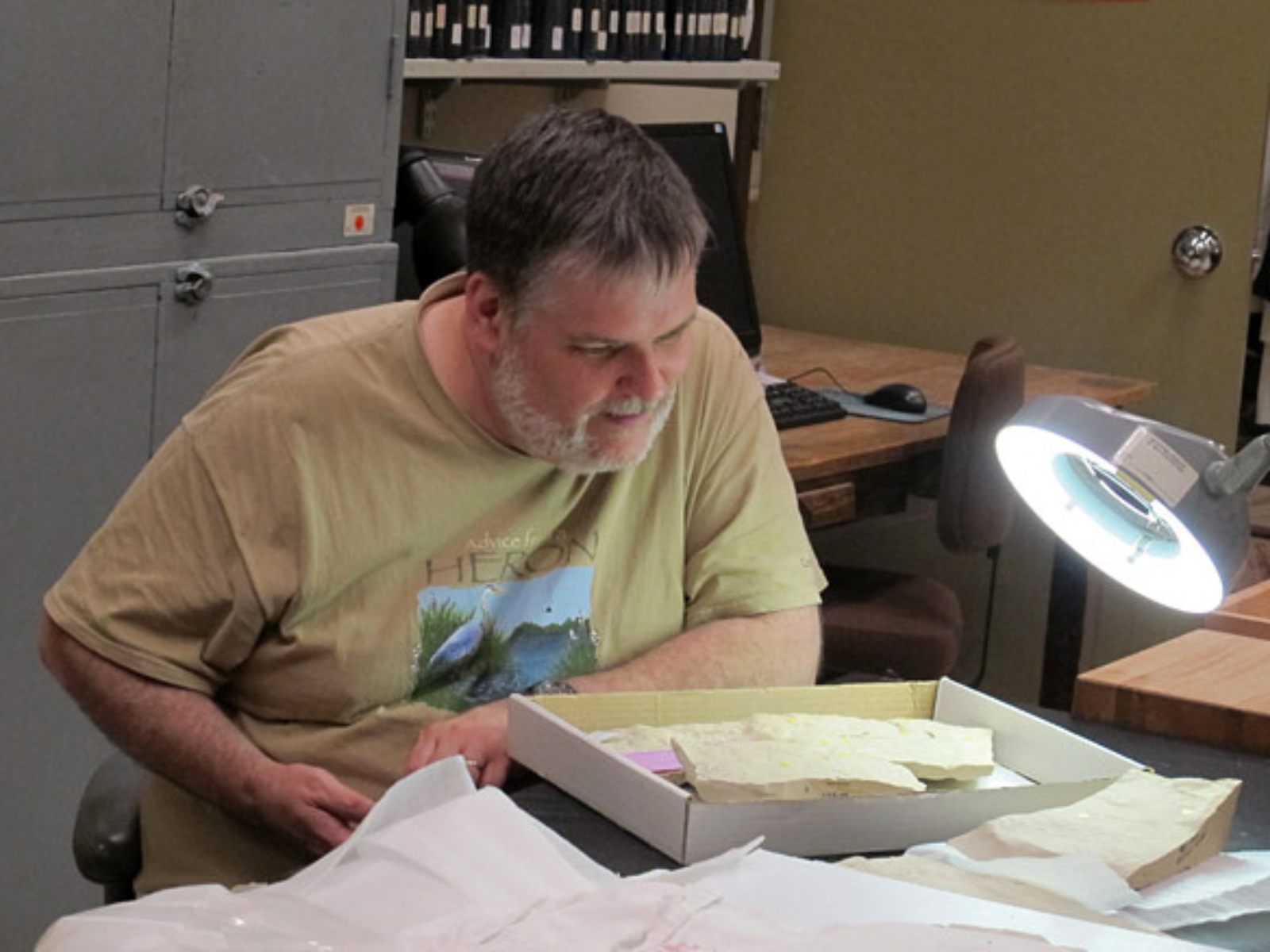

Moss voucher specimens awaiting documentation.