At some time or another, we have all experienced a really satisfying day at work, or perhaps more often, a day that left us wanting to vent our frustrations. Today we might use social media to voice these emotions. In the days before Facebook or Twitter, Joe Maruca documented his working life in a ‘Secret’ notebook filled with amusing cartoon sketches.

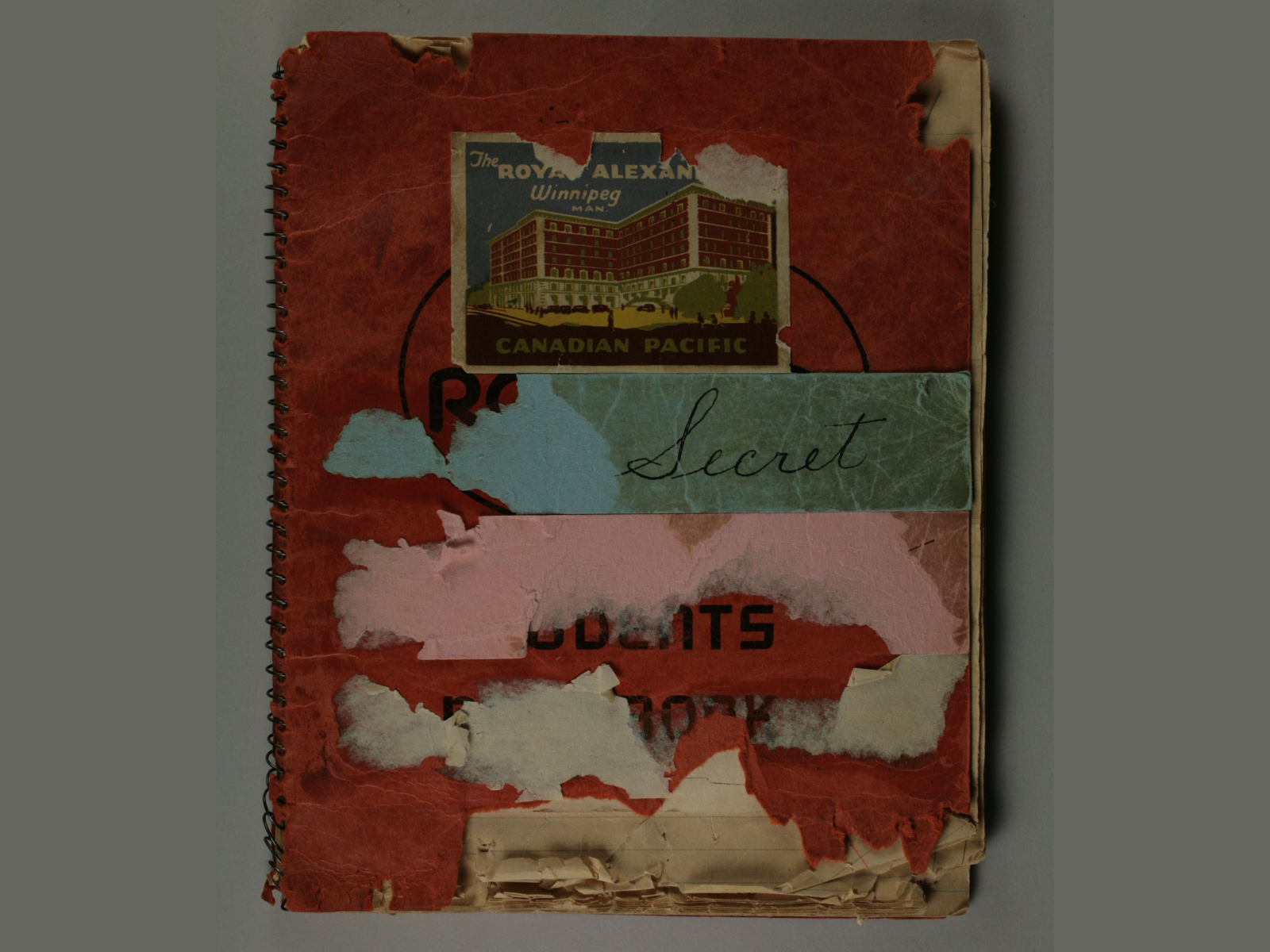

Recently, I processed a fascinating collection of family items donated by the children of Joseph and Alice Maruca. These include a porter’s uniform, photographs, documents and the notebook. Joe’s father, Vincenzo had immigrated from Italy in 1920 and worked as a freight carpenter at the CNR shops in Transcona. In the 1950s Joe Maruca was employed as a Porter Captain at the Royal Alexandra Hotel in Winnipeg. The “Royal Alex” was part of the Canadian Pacific chain and was considered one of the finest hotels in western Canada. It opened its doors on Higgins and Main in 1906 and served as a social centre of Winnipeg until 1967. The hotel was demolished in 1971.

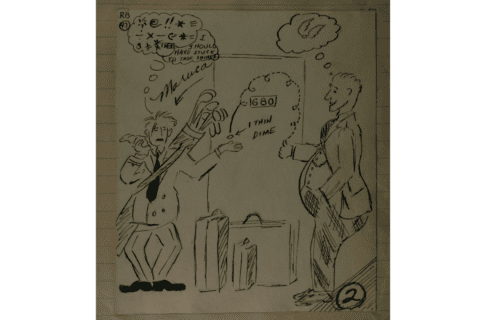

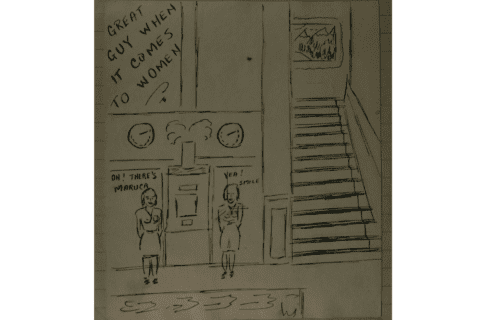

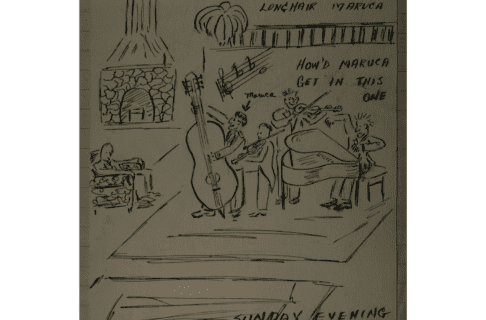

Through Joe’s sketches we can see a humorous account of the inner workings of the Royal Alexandra as viewed through the eyes of the front line staff. There is the frustration of being under tipped by a wealthy client or being “twisted” by a co-worker. The word twist can be as slang expression meaning to cheat or have something wrench from your grasp – when a fellow porter takes your next client and tip! We also see Joe as the hero of the story and a bit of a lady’s man.

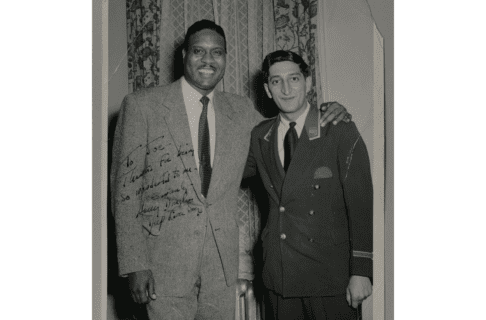

The Royal Alex was home-on-the-road to musicians who came to play at the hotel or local hotspots such as the Don Carlos night club. Included in the donation is a collection of signed photographs of notable African-American musicians of the era – The Mills Brothers, The Charioteers, Nellie Lutcher and The Deep River Boys. Joe enjoyed a positive reputation among these performers and the service he provided would have been in marked contrast to the discrimination they faced at segregated American hotels in the 1950s. “When you’re in Winnipeg ask for Joe, he’ll take good care of you” was the message passed among the performers. A couple of his sketches suggest that Joe may have had musical dreams of his own.

As new artifacts are added to the Manitoba Museum’s collection, our understanding of the past expands. Donations from families like the Marucas help to give us a glimpse the life of a talented ‘average working Joe’.

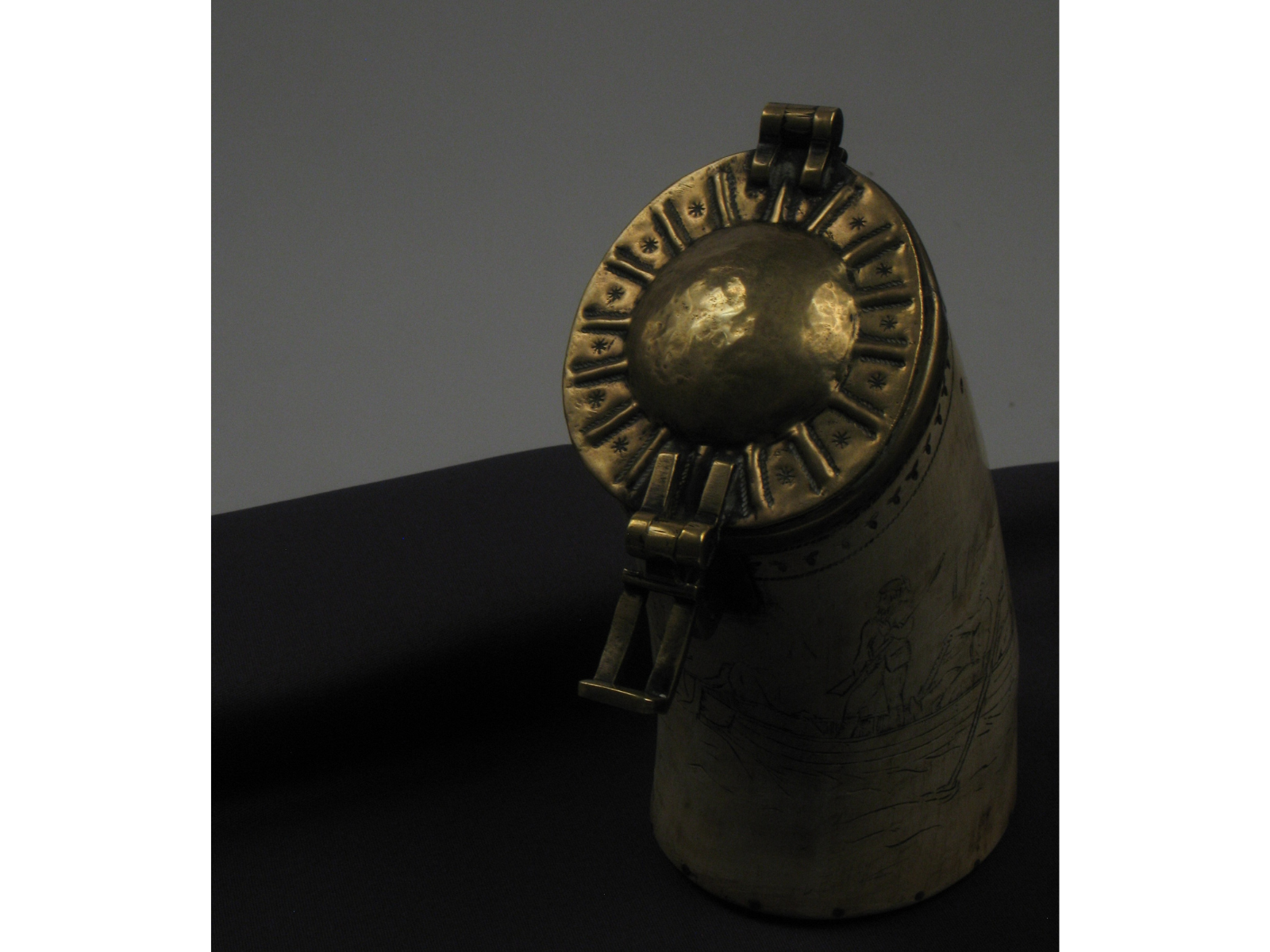

In 1993, the remains of a woman were found at Nagami Bay (Onākaāmihk) west shore of Southern Indian Lake. The following year, community members from South Indian Lake and archaeologists worked together to recover our ancestor in a respectful and honourable way. The story of her miskanow, life journey, was pieced together from her remains and her belongings and told in the book

In 1993, the remains of a woman were found at Nagami Bay (Onākaāmihk) west shore of Southern Indian Lake. The following year, community members from South Indian Lake and archaeologists worked together to recover our ancestor in a respectful and honourable way. The story of her miskanow, life journey, was pieced together from her remains and her belongings and told in the book