Posted on: Monday August 8, 2016

Usually cow pies are extremely uninteresting features of a prairie landscape (and one to usually avoid) but this month something funny was happening with them at the Nature Conservancy’s Yellow Quill Prairie that made me look twice. For starters, one day I saw a cow pie moving.

As it turns out though, it wasn’t really the cow pie that was moving: it was a toad, a Canadian Toad (Anaxyrus hemiophrys) to be specific. As I stepped next to a cow pie in one of my research plots, the aforementioned toad made a short hop. It took me a few seconds to actually find the toad as it blended in with the cow pies and dried grass quite magnificently. I had never really appreciated how well the colour of these creatures helps them to blend in with their surroundings. The toad looked hot and, as I was leaving for the day and no longer needed the water in my bottle, I decided to give him a shower. To my surprise he made a happy chirping sound and wiggled his back. Good deed for the day completed!

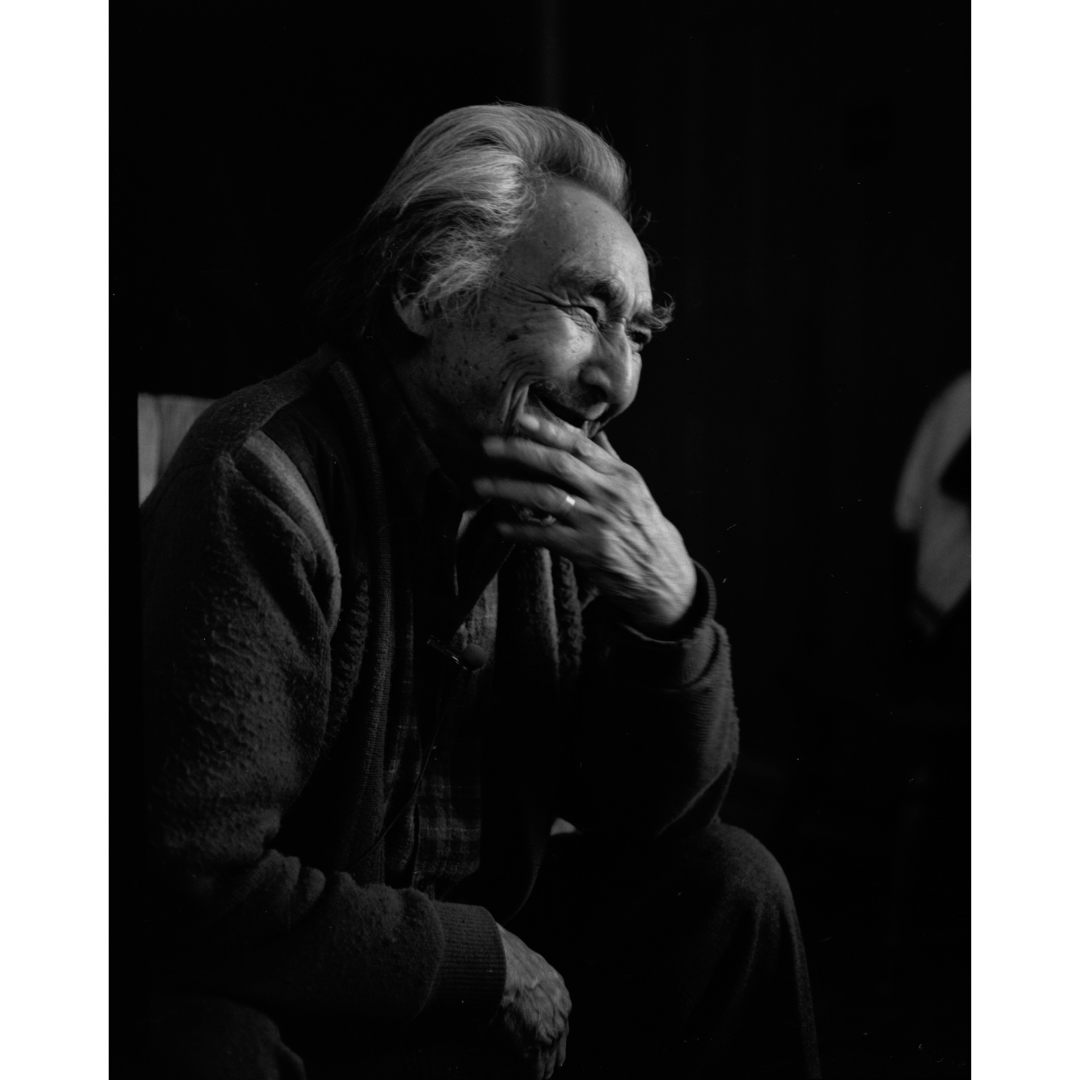

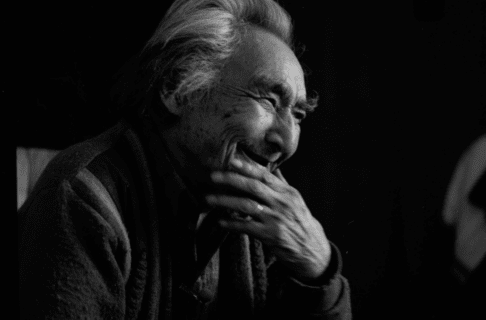

I thought the cow pie was moving when this little toad hopped away!

This Canadian Toad (Anaxyrus hemiophrys) really appreciated the shower I gave it.

The other interesting thing happening to the cow pies was that they were becoming fungal gardens. We rarely appreciate the fact that the soil beneath our feet is just as (actually, probably much more) biologically diverse as the world above ground. Prairie soils are loaded with all kinds of insects, bacteria, nematodes, and fungi living in and around the prolific plant roots, some of which go down five meters! So the part of the prairie plants that you actually see is only their “head”; the rest of their “body” is underground.

Fungi live most of their lives as hyphae which are the fungal equivalent of “roots” so during dry years, you won’t even know that they exist. But when it gets wet (like it did the day I started my field work), the reproductive stage of the fungi is triggered and they begin producing mushrooms. The wet weather this year combined with the high nutrient cow pies resulted in a prolific “mushrooming” of the prairie. On one cow pie I saw a species that we have almost no specimens of in our collection: a Bird’s Nest Fungus (Cyathus sp.). There was no way around it; to get a specimen of this fungus I would have to pry the tiny cups out with my hands. Would I stick my fingers in feces for science? As it turns out the answer is YES! Fortunately, I always bring hand sanitizer and gloves with me.

Image: All the cowpies at Yellow Quill Prairie were covered with mushrooms this July.

This little Bird’s Nest Fungi (Cyathus sp.) will make a great addition to the Manitoba Museum’s fungal collection.

The warm wet weather provided the perfect growing conditions for coprophilous fungi like this one.

The Yellow Quill Prairie is currently being sustainably grazed by cattle, which is why the cow pies are even there. Doing so increases the fungal diversity of the prairie as some species are strictly coprophilous (e.g. poop-loving) and would not otherwise be there. Although these fungi would have initially evolved to decompose Bison pies, cow pies are not much different from them, and therefore cattle fill a similar ecological role.

As the prairie dried out the mushrooms, having completed their spore-dispersal goal, began to wither away in the heat of the day. But I won’t forget the brief glimpse that I got of the diversity that lay beneath my feet.