Posted on: Tuesday December 4, 2018

Visitors to the Manitoba Museum are currently enjoying two hockey themed exhibitions – Hockey: The Stories Behind our Passion from the Canadian Museum of History and Manitoba Heart of Hockey developed and produced by the Manitoba Museum. Both exhibitions examine the meaning of hockey in the lives of Canadians as players and their families, coaches, officials, broadcasters, and fans.

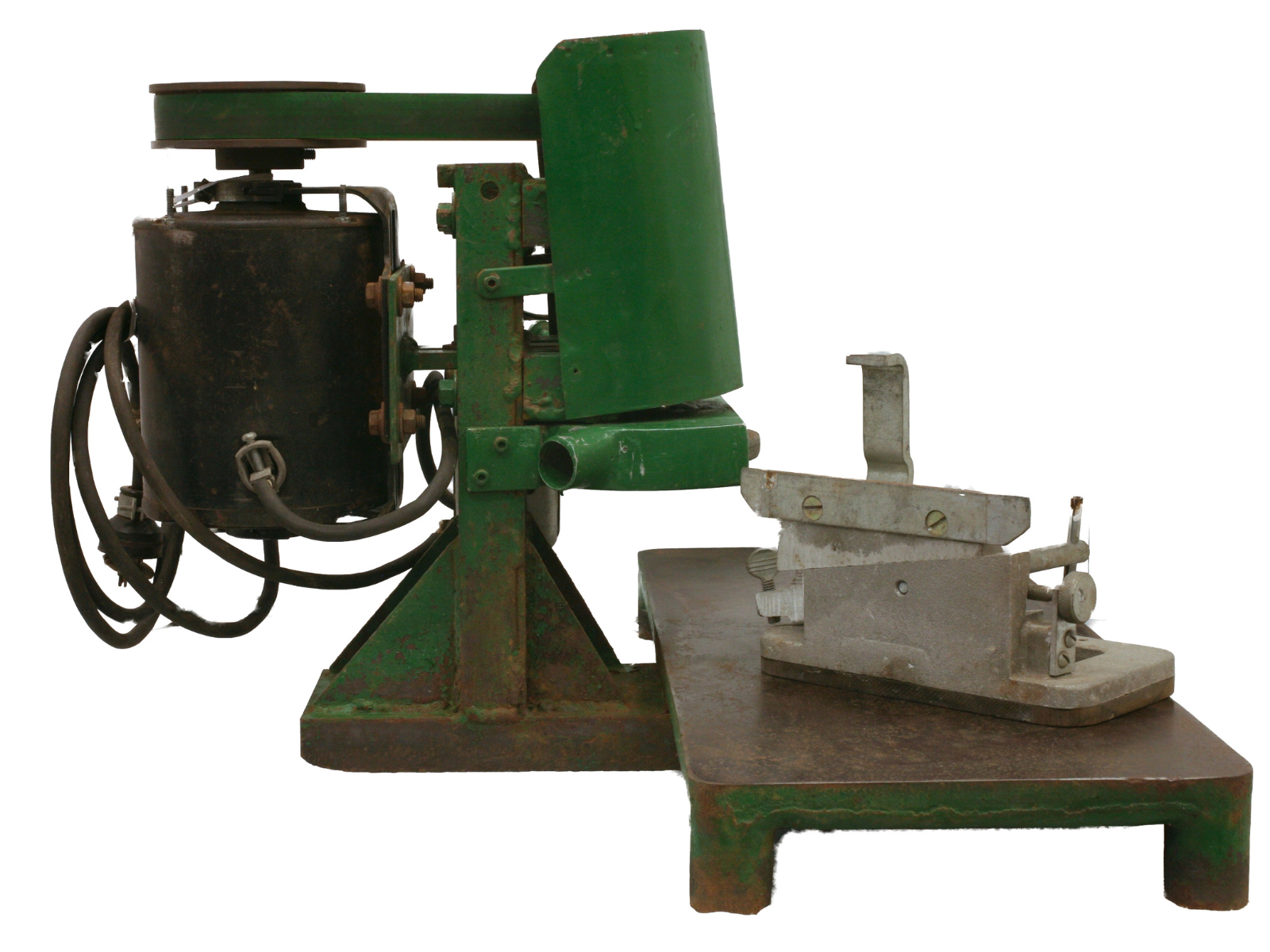

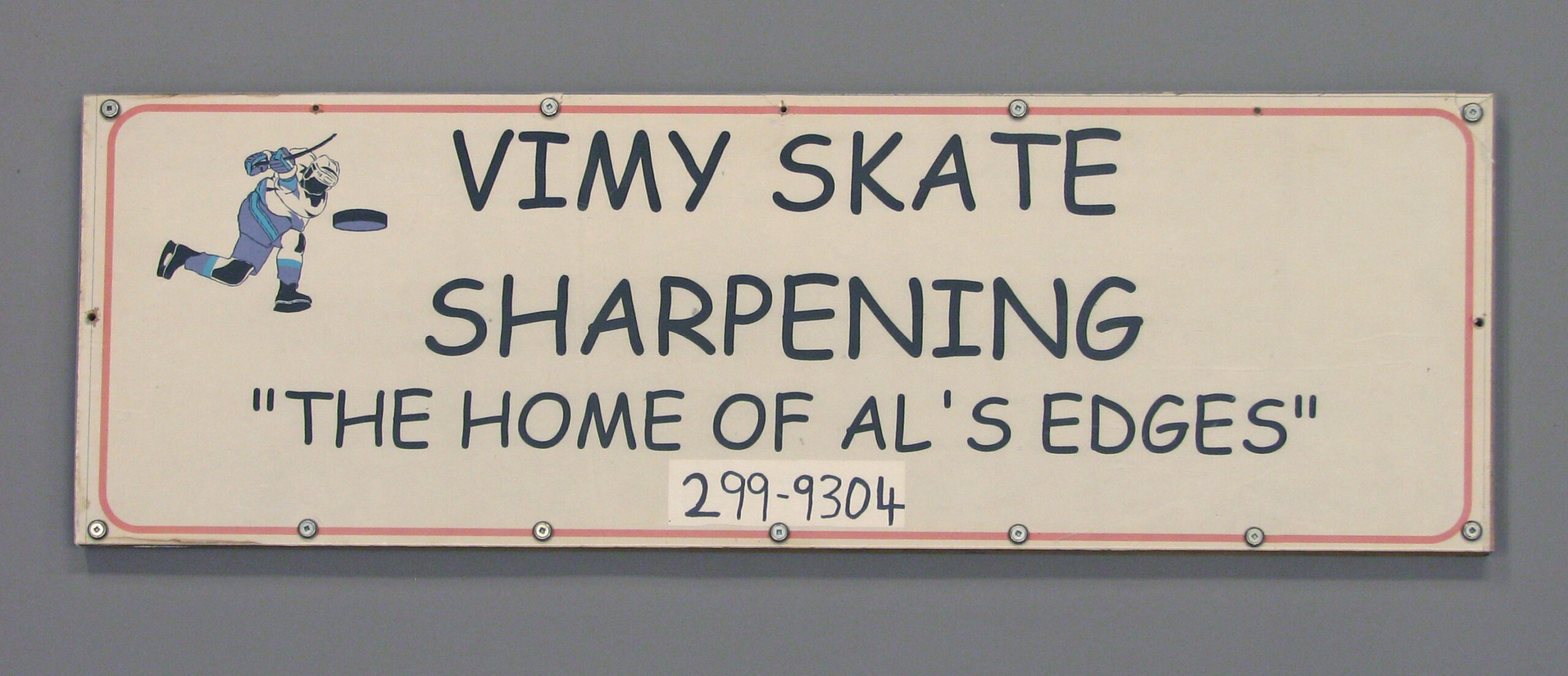

One person who literally helps to keep the game running smoothly is the skate sharpener. A trained operator can optimize a player’s performance by skillfully honing the pitch and contour of the blade to match their stride and style. Recently, the Manitoba Museum received a donation of an early skate sharpening machine along with the sign for “Vimy Skate Sharpening” run by Allan Merko.

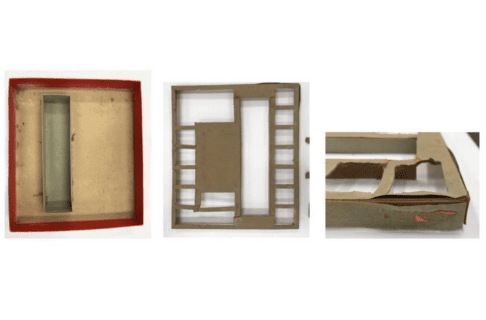

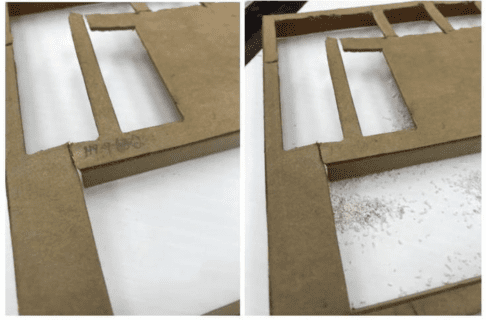

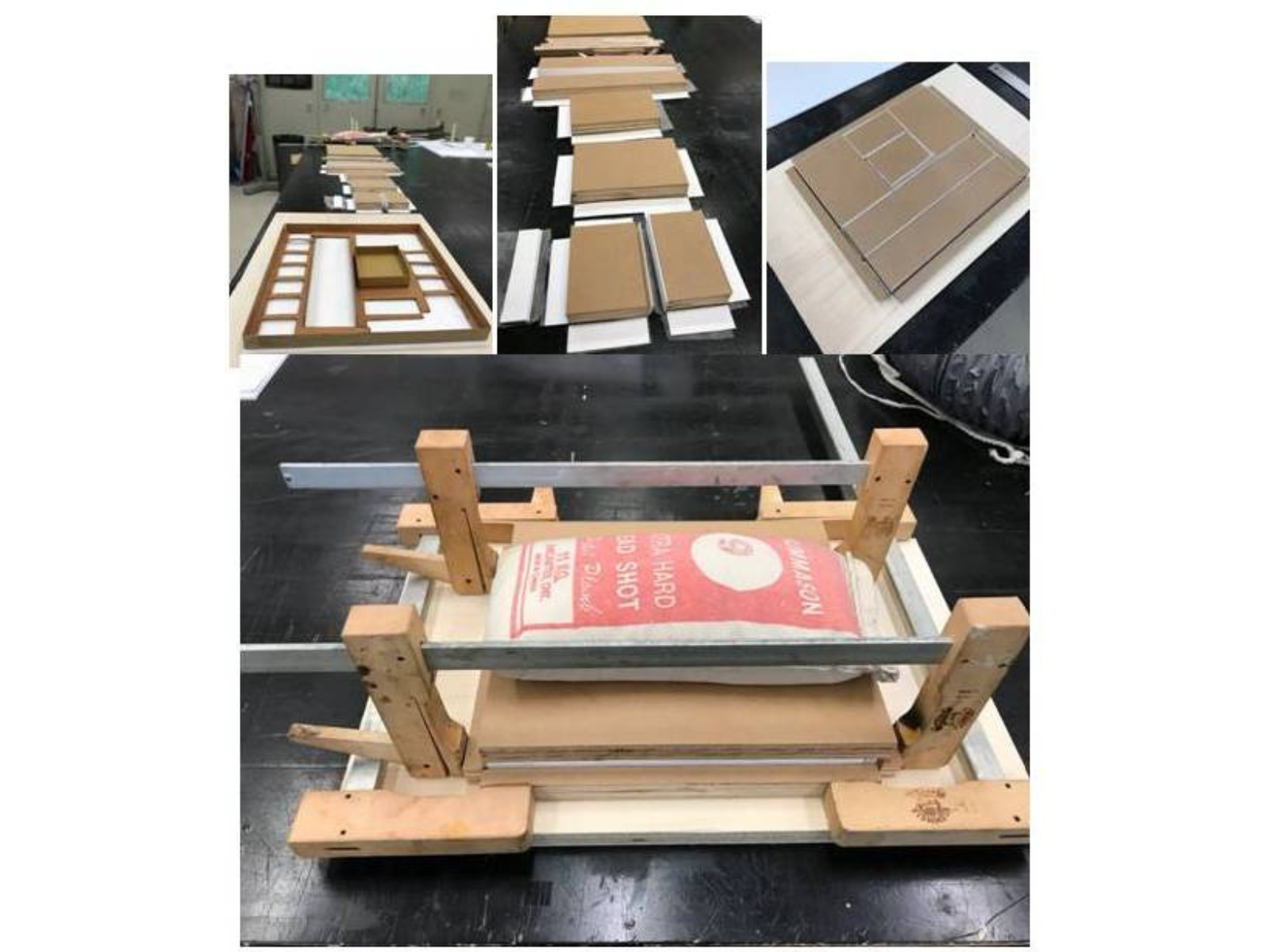

Skate Sharpener. Catalogue Number: H9-38-822 ©Manitoba Museum

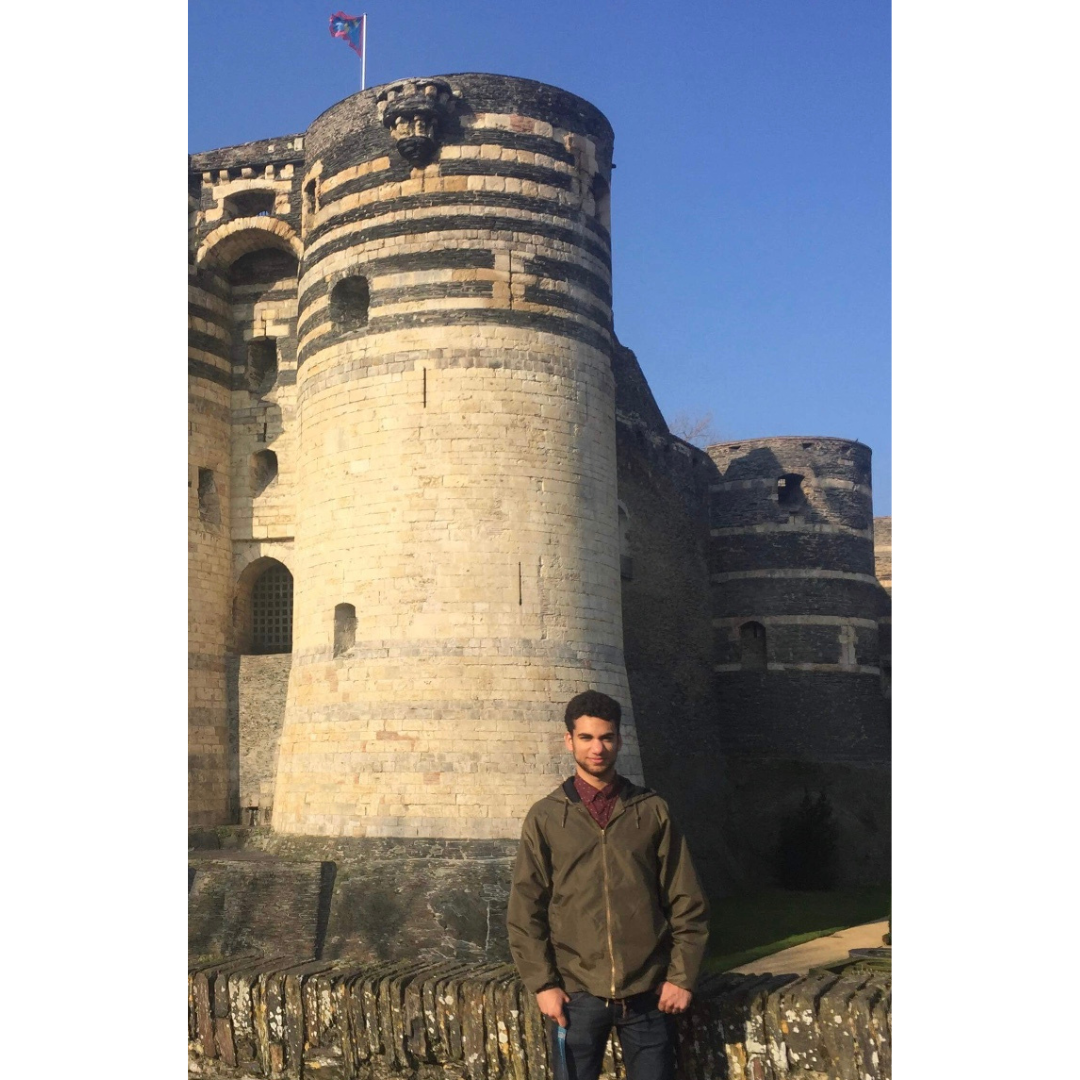

Allan Merko (centre); Courtesy of the Merko family.

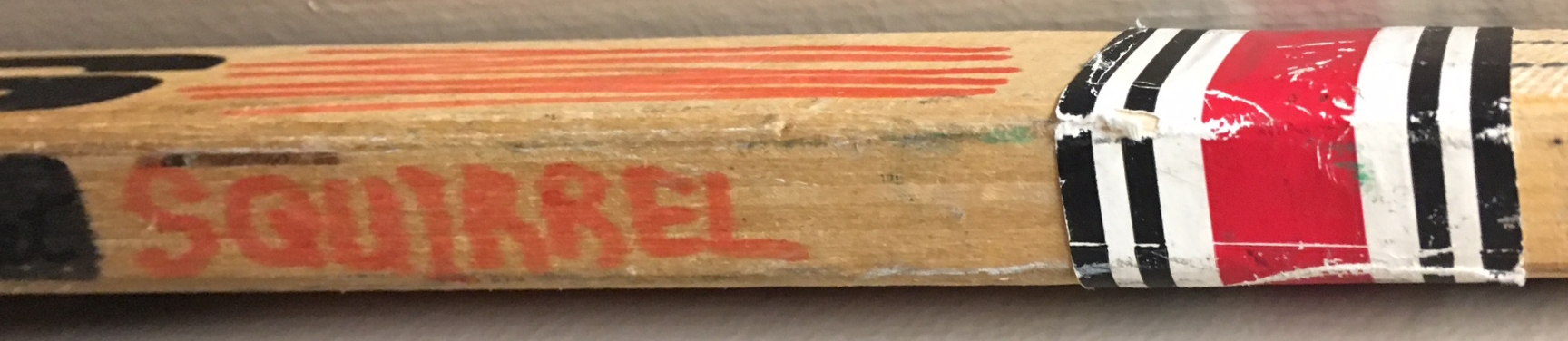

Allan Merko was a Canadian lad with a passion for hockey. Times were tight growing up in Gilbert Plains, Manitoba, so Allan collected bottles to cash in for the deposit in order to pay for his basic equipment – skates, gloves, and a stick. After a move to Ethelbert, he played centre for the Ethelbert Eagles and later the Sabres wearing jersey No. 9. His skill and speed on the ice earned him the nickname “Squirrel”. Later, he would take up coaching the younger Ethelbert Oilers team and teach power skating. His daughter fondly remembers growing up as a ‘rink rat’ and hanging out with her dad.

Allan’s Stick; Courtesy of the Merko family.

Allan was more than just a player and coach. He also operated the Zamboni and created and maintained the ice at the Ethelbert Arena. Sometimes he flooded the ice between periods in full hockey gear while his team rested in the dressing room! Being mechanically inclined, Allan taught himself how to sharpen skates on an unused machine in the arena thus saving local skaters a 125 km round trip to Dauphin.

Following a move to Winnipeg in the late 1990s, he set himself up in the skate sharpening business at the Vimy Arena in St. James. His love of the game shone through in the service he provided to his customers. Al, as he was known, always remembered their names and preferences. One young customer sent him a note at the end of the season – “Thank you for sharpening my skates all year and thanks for taking an interest in my ringette. I had a great time at Nationals”. Al took the time to listen to parents tell stories of their children’s accomplishments. One mom recalled he would offer “the warmest of hugs especially when …I was run ragged during hockey season.” Sadly, Al passed away in 2012 which coincided with the last year of operation for the Vimy Arena.

The contact between blade and ice sets hockey and ringette apart from other team sports. In arenas and sporting shops across the county, it is the skill of the operator at the skate sharpening machines that keeps the players skating their best.

Image: Al Merko at Vimy Arena; Courtesy of the Merko Family.

Sign. Catalogue Number: H9-38-822 ©Manitoba Museum