On the morning of June 10, 2021, early risers across Manitoba will see a partial eclipse of the sun from most of Manitoba.

TO VIEW THE ECLIPSE YOU MUST USE ONE OF THE SAFE METHODS DESCRIBED BELOW.

The eclipse is already underway by the time the sun rises, and only lasts about an hour after sunrise, so this will be an early morning event on June 10.

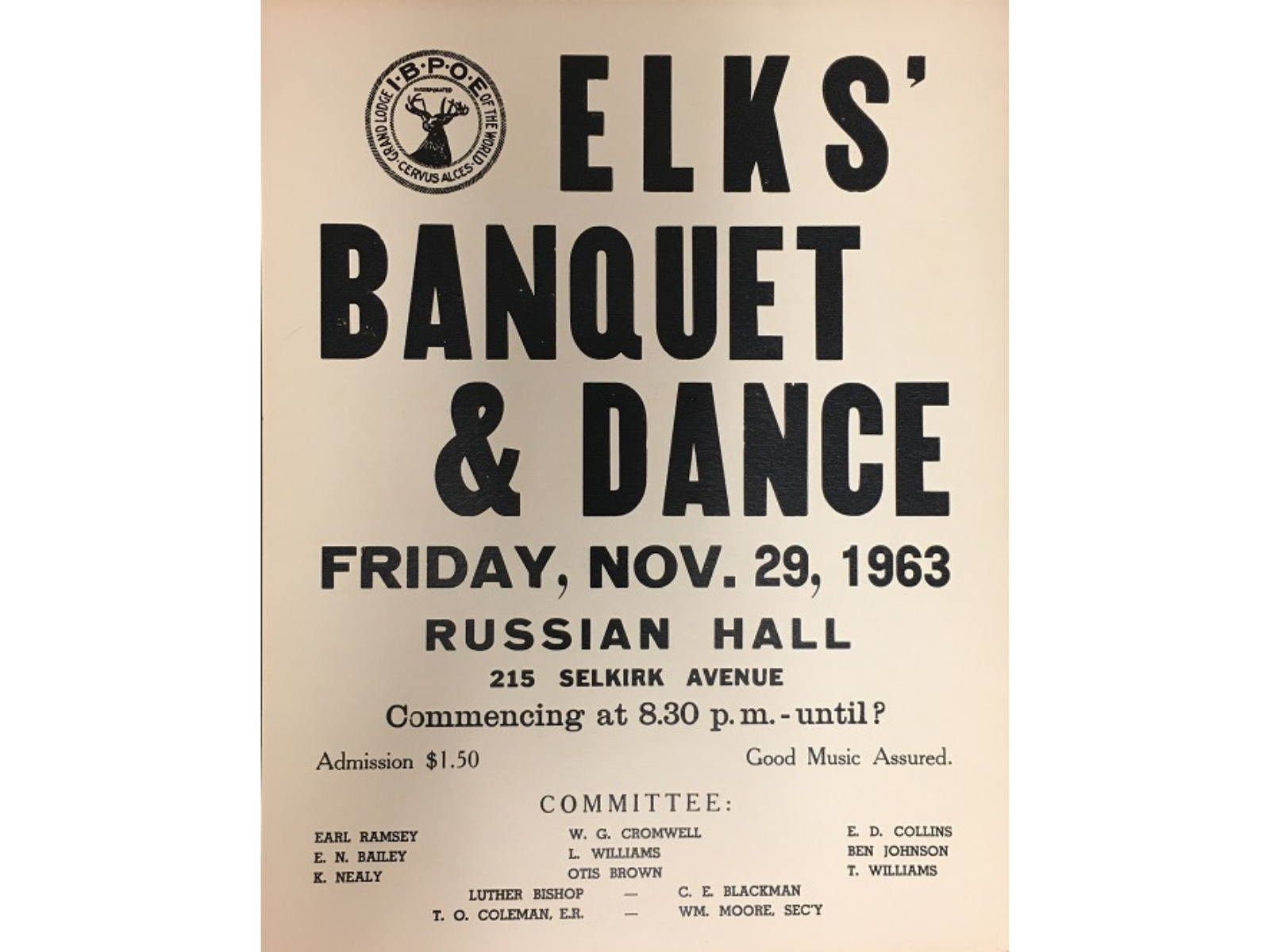

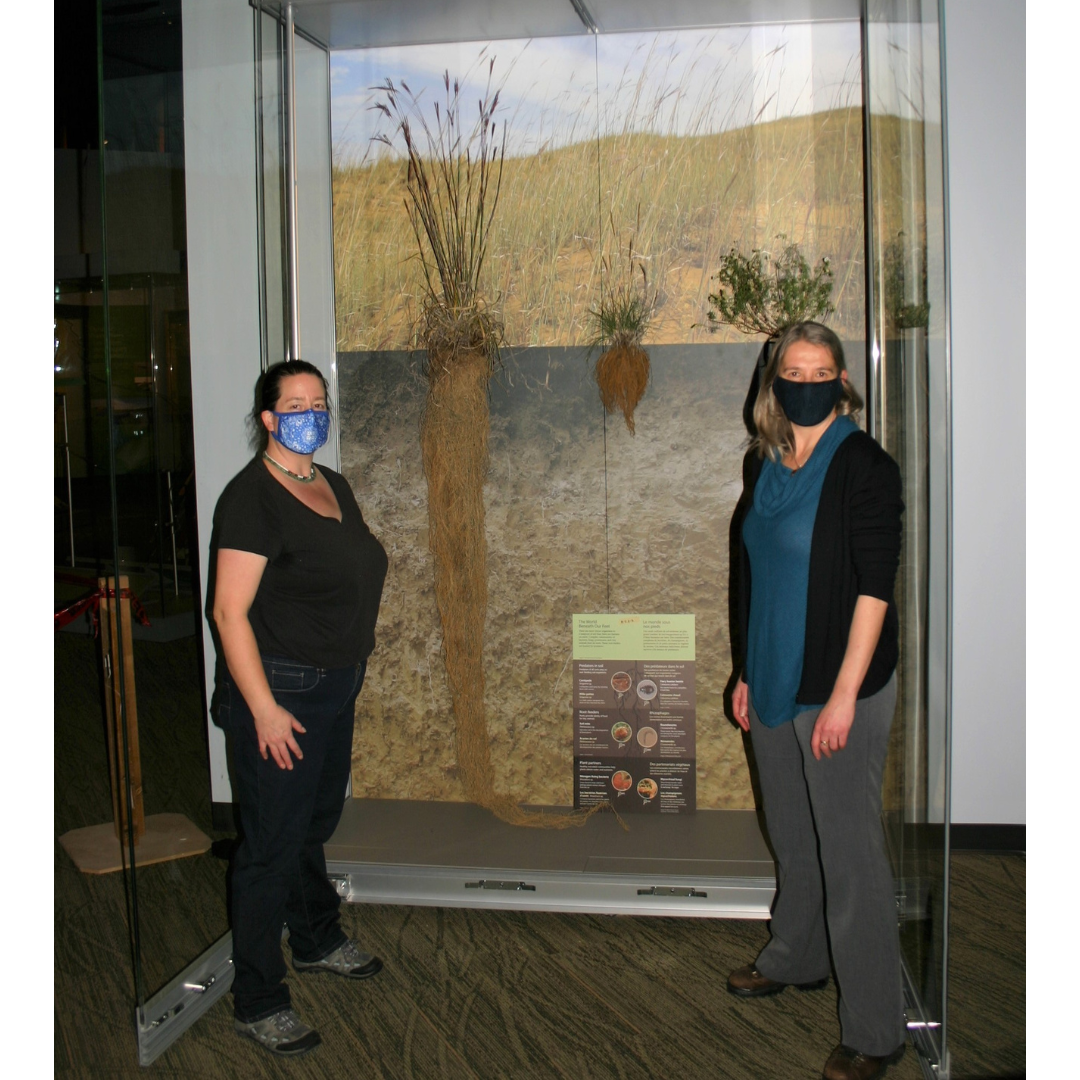

From Winnipeg, the rising sun on June 10, 2021 will appear similar to this view, shot during the 2017 eclipse. (Image: Scott D. Young)

What is Happening?

As the moon orbits the earth, it sometimes crosses the sun from our point of view in an event called a solar eclipse. When the moon only covers part of the sun we see a partial eclipse – this is what we will see from Manitoba. From other areas of the earth, the moon will appear to cross the center of the Sun, blocking out most of the sun’s rays in an annular or “ring” eclipse. This occurs because this eclipse happens when the Moon is near its farthest point from the Earth and so doesn’t appear quite big enough to cover the entire sun. When an eclipse happens when the moon is near its closest point to earth, the moon’s disk can cover the entire solar disk and a total solar eclipse results. A total solar eclipse is one of the true spectacles of nature, worth traveling to see. A total solar eclipse crossed the central United States in August 2017. Manitoba last witnessed a total solar eclipse on February 26, 1979.

For more details on the mechanics of eclipses, see NASA’s explanation here.

How Can I Observe the Eclipse Safely?

The sun is always too bright to observe directly without special eye protection. Sunglasses are not sufficient – a specially-made solar filter is required to prevent permanent eye damage. Eclipse glasses purchased for the 2017 total solar eclipse are sufficient as long as there are no scratches or holes in the silver Mylar material. A #14 welder’s glass (available at welding supply shops) will allow you to view the sun safely. No other materials should be used – while dark plastic or Mylar balloon material may dim the sun’s image in the visual range, the invisible ultraviolet and infrared light can still enter your eye and cause irreversible damage or even blindness.

Due to COVID restrictions over the past year, the Museum’s shop is not open, and we do not have any eclipses glasses for sale.

If no appropriate filter is available, you can use a pair of household binoculars to project an image of the sun using the method described here. Note: DO NOT LOOK AT THE SUN THROUGH BINOCULARS! Make sure you follow the instructions carefully, including the part about turning the binoculars away from the sun every few minutes to let them cool down. The Museum is not responsible for any injury or damage due to solar viewing; if you’re uncertain it’s best to watch the event online.

If you have a telescope, do not look at the sun with it or you will instantly and permanently blind yourself. Safe solar filters that fit over the front of the telescope are available for telescopes through mail order, but they will cost $100 or more and at this point are unlikely to arrive before the eclipse. You can use your telescope to project an image of the sun similarly to the binocular method shown above, but the increased heat may damage your telescope. This is not recommended unless you already know how to observe the sun properly.

When and Where Should I Look?

All of Manitoba can see the partial eclipse, although most of it occurs before sunrise; we catch just the end of it. The annular or ring phase is only visible from a path that starts in northwestern Ontario, goes up over the north pole, and down into eastern Russia. With provincial and international borders closed at the time of writing, Manitobans will have to be content with a partial eclipse and an online view of the annular portion.

For all of Manitoba, the eclipse is already underway as the sun rises – check your local newspaper or heavens-above.com for sunrise and sunset times for your location. In Winnipeg, the sun will be about half-eclipsed when it rises at 5:27 am CDT in the northeast, and the moon will uncover the sun as they both rise. By 5:55 am CDT (less than a half-hour after sunrise) the eclipse will be over from Winnipeg.

Points farther north in Manitoba will have better views. From Churchill, Manitoba, the sun rises at 4:08 am CDT with the eclipse beginning 4 minutes later. At 5:09 am CDT the sun reaches a maximum of 85% eclipsed before the moon moves on and uncovers the sun. From Churchill the eclipse ends at 6:08 am CDT. Flin Flon will see a maximum 75% eclipse just after sunrise; Thompson reaches 85% about 10 minutes after sunrise.

Links

https://www.timeanddate.com/eclipse/map/2021-june-10?n=265 – eclipse times and simulated views for any location

https://eclipsophile.com/2021ase/ – maps and weather prospects for the eclipse

https://science.nasa.gov/eclipses/ – eclipses and transits overview