Like many of you, I am eagerly awaiting spring so that I can start planting my vegetable garden. There’s nothing better than eating bruschetta with freshly harvested vine-ripened tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum) and steamed green beans (Phaseolus sp.) with fried cream (see recipes at the end). My mouth drools just thinking about it! But the funny thing about tomatoes and green beans is that they are not actually vegetables: they are fruits masquerading as vegetables.

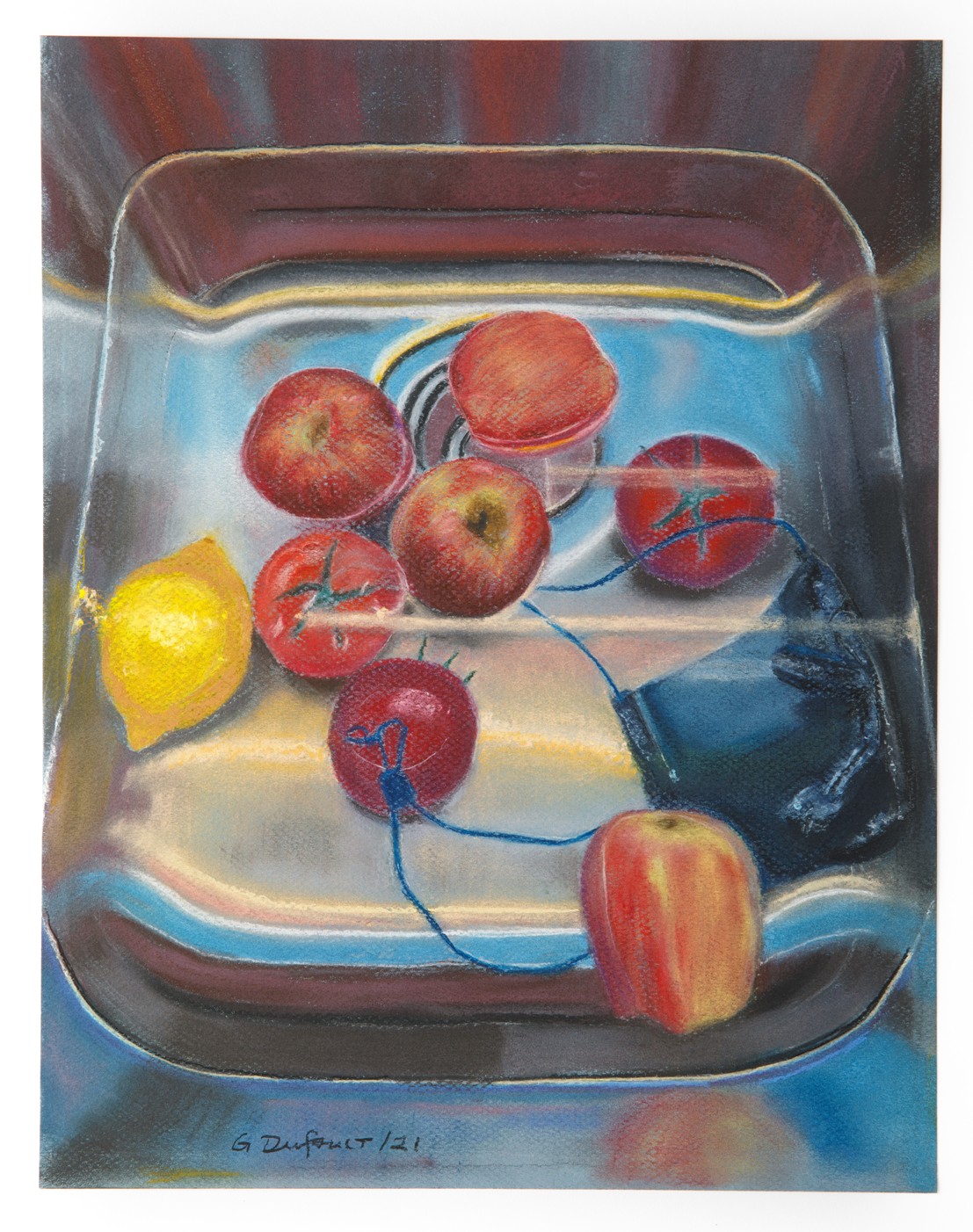

In fact, there are many other things we think of as vegetables that are actually fruits: avocados (Persea americana), cucumber (Cucumis sativus), eggplant (Solanum melongena), okra (Abelmoschus esculentus), olives (Olea europaea), peppers (Capsicum spp.), snow peas (Pisum sativum), squashes including pumpkin (Cucurbita spp.), tomatillos (Physalis spp.) and zucchini (Cucurbita pepo). We tend to define fruits as plant parts that are sweet and vegetables as plant parts that are not sweet. However, botanically, a fruit is a ripened ovary that contains seeds inside it, so all of the aforementioned plants meet the definition of a “fruit”, even though we rarely eat them the way we eat fruit (in a pie with ice cream!). For this reason, some people call them “vegetable fruits”.

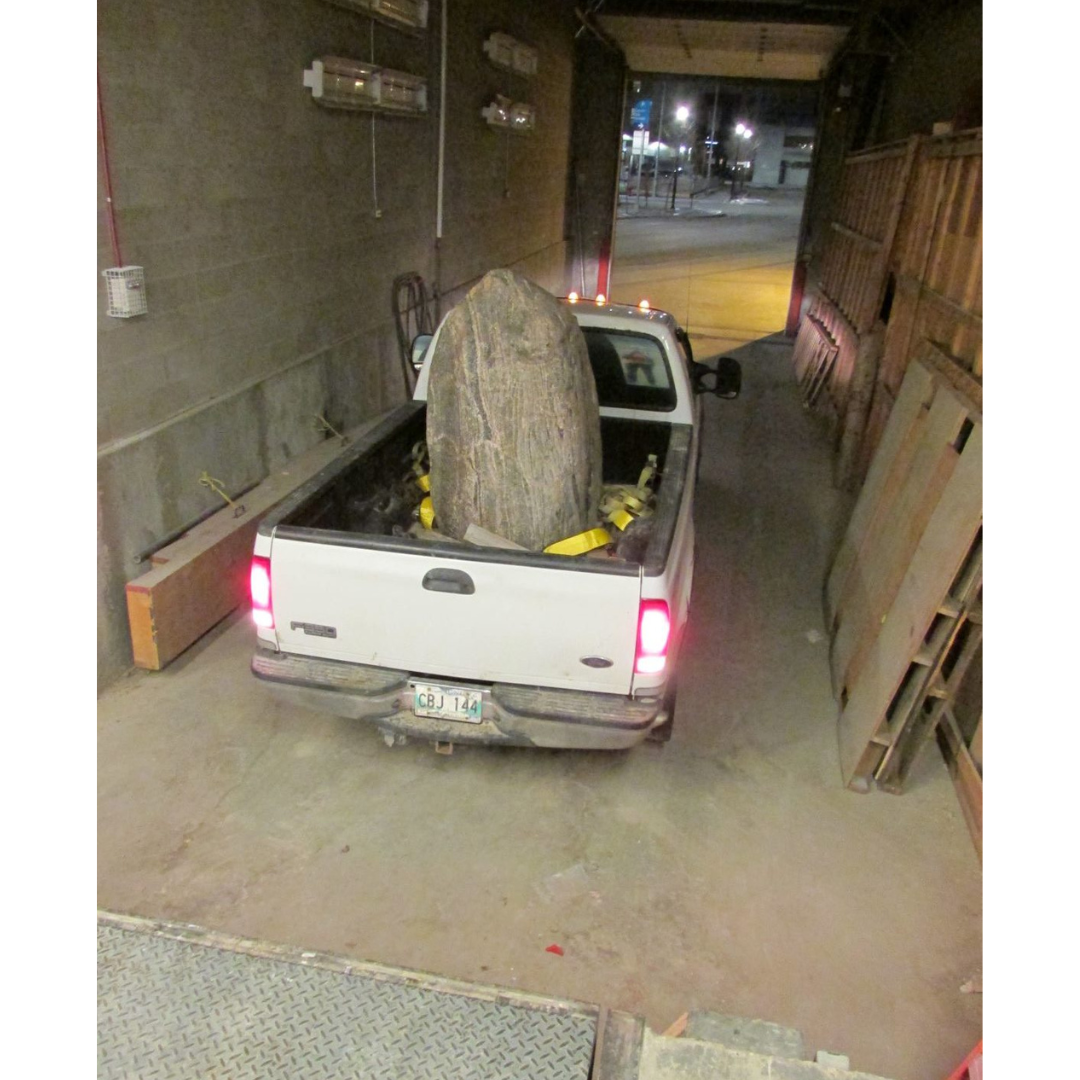

When you eat fresh green beans, you are eating the fruit (outer pod) and the immature seeds inside. From Wikimedia Commons.

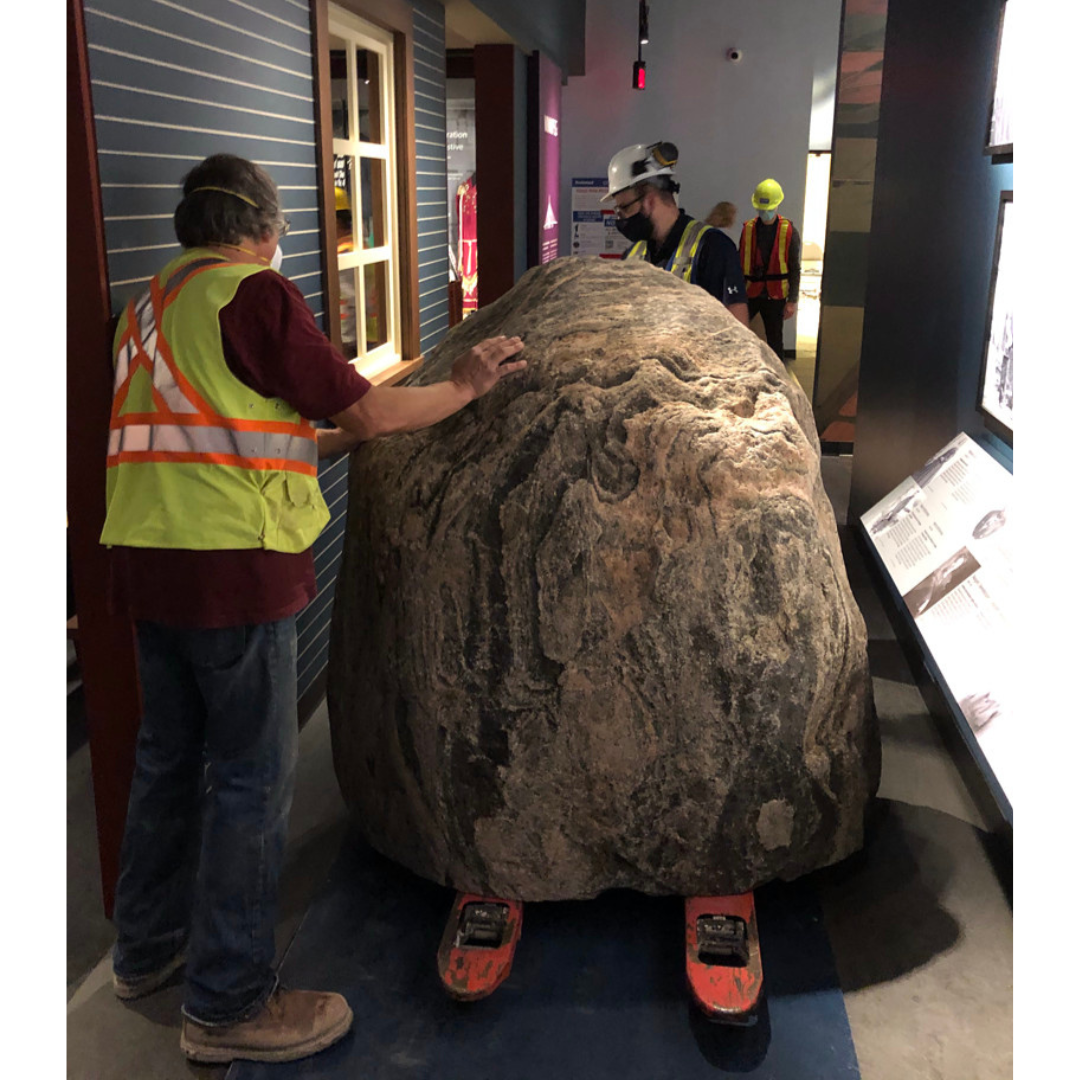

Although it is not sweet, avocado is still considered a fruit because of the seed inside. From Wikimedia Commons.

Complicating things further is the fact that the fleshy parts of some “fruits”, like apples (Malus domesticus), pears (Pyrus spp.) and strawberries (Fragaria spp.), are not actually ripened ovaries at all, but greatly enlarged fleshy petals, or upper flower stalks.

“Aha” you might be thinking, what about bananas (Musa spp.)? They don’t have seeds. You may have noticed though, that there are little black specks inside bananas; those are tiny ovules (unfertilized seeds) that never ripened because the plants are sterile. Since people don’t usually like spitting out seeds, plant breeders have found ways to produce sterile, seedless varieties (often with an odd number of chromosomes) of certain plants such as citrus fruits, watermelons (Citrullus lanatus) and bananas.

The apple “fruit” is actually just the core; the fleshy part we eat is formed from petal tissues. From Wikimedia Commons.

Seeds inside a wild, fertile banana. From Wikimedia Commons.

There are actually four different kinds of vegetables, which vary according to the part of the plant you are actually eating: roots, stems, leaves, or inflorescences. Root vegetables are either fairly slender taproots (e.g. carrots or Daucus carota), or swollen, tuberous roots (e.g. sweet potato or Ipomoea batatas). Roots store starch that the plant can use the following year to grow new leaves.

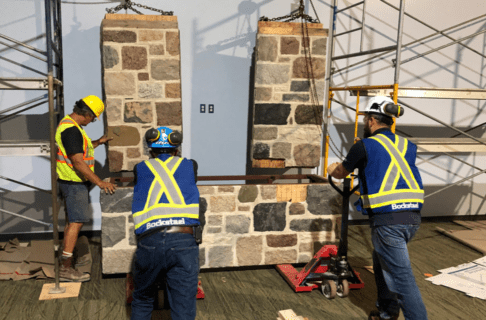

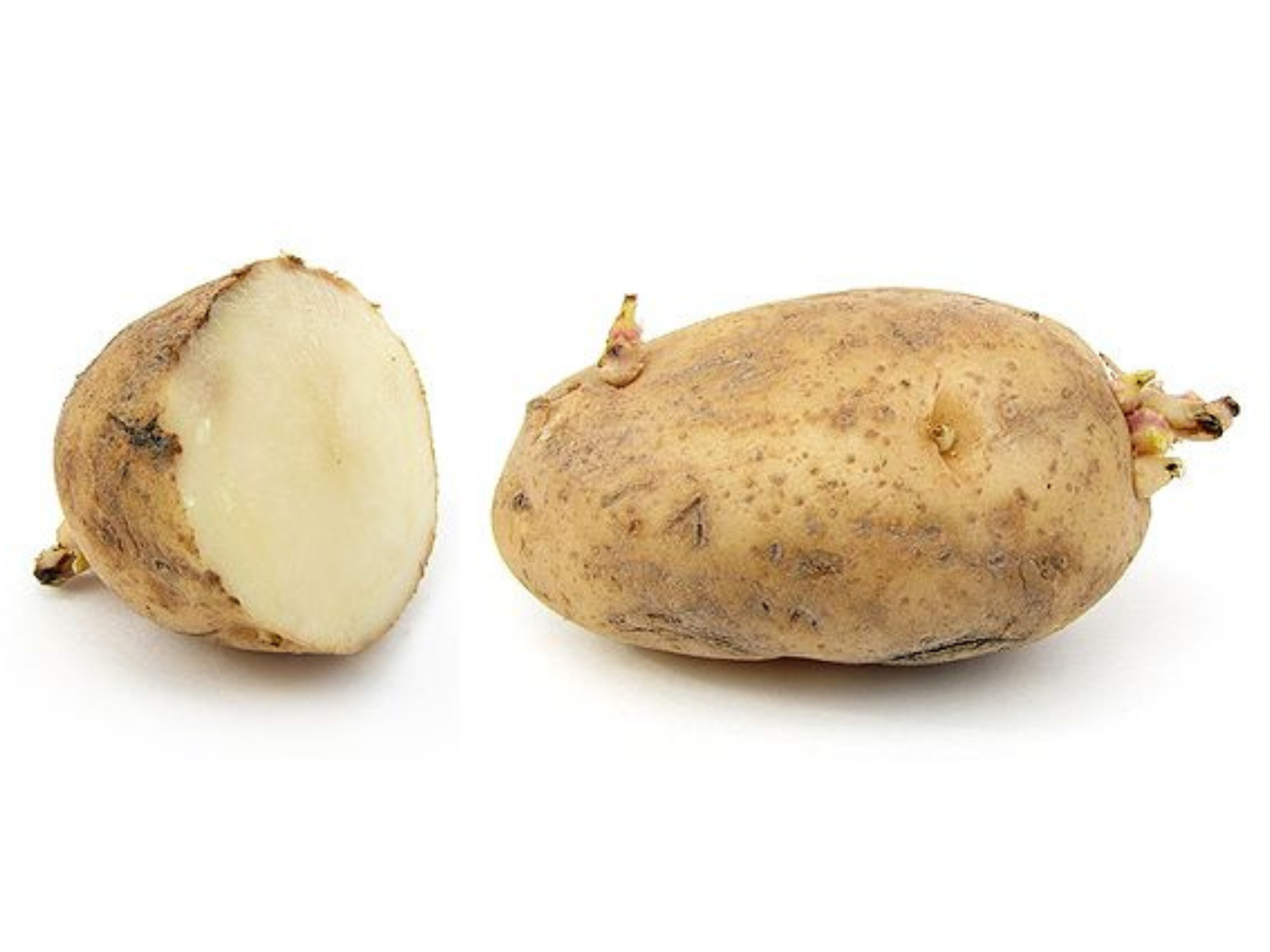

Some of the vegetables we eat consist of stems (e.g. corms, tubers and rhizomes) or leaves (e.g. bulbs) that grow underground. Like roots, these structures are fleshy and store starch. However, corms grow upright and rhizomes grow horizontally. Tubers, on the other hand, can grow in any direction. Tubers also possess tiny “eyes” all over it that represent leaf buds. For this reason, you can plant a single tuber (or just part of it as long as there is an “eye” on it), and it will grow into a whole new plant.

Seed potatoes are tubers that can be planted to grow new plants. From Wikimedia Commons

The non-green parts of bulbs, like onions (Allium cepa), are actually special, fleshy leaves that store starch. Some vegetables, like broccoli (Brassica oleracea), actually consist of upper stems and unopened flowers, known as inflorescences. See the table below to find out what your favorite vegetables actually are.

Table 1. Plant parts that vegetables represent

| Main plant part | Category | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Root | Beets, burdock, carrot, cassava, celeriac, daikon, horseradish, parsnip, radish, rutabaga, sugar beet, sweet potato (Ipomoea), turnip | |

| Stem (above ground) | Stalk | Asparagus, bamboo shoots, celery, cinnamon, fiddleheads, heart of palm, kohlrabi, rhubarb |

| Stem (below ground) | Corm | Taro, water chestnut |

| Rhizome | Galagal, ginger, lotus, turmeric, wasabi | |

| Tuber | Jicama, oca, potato, sunchokes, yam (Dioscorea) | |

| Leaf (below ground) | Bulbs | Garlic, leeks, onion, shallots |

| Leaf (above ground) | Greens | Arugula, bok choi, Brussel sprouts, cabbage, Chinese mustard, dandelion, endive, goosefoot, herbs (e.g. basil, oregano, rosemary), kale, lettuce, mustard greens, nettle, rocket, spinach, sorrel, Swiss chard, watercress |

| Inflorescences | Artichoke, broccoli, capers (flower buds), cauliflower, rapini |

To finish off, here are two of my favourite “vegetable fruit” recipes. Unfortunately, you’ll just have to wait a few more months to try them.

Bruschetta

Coarsely chop however many fresh tomatoes you want to eat, and put in a bowl. Mix in coarsely chopped onions and some sliced fresh basil. Pour in enough olive oil and balsamic vinegar to generously coat. Season with salt and pepper and toss. Let sit for 15 minutes. Heap onto garlic toast and savour the flavour of summer!

Beans with Fried Cream

Steam fresh yellow or green wax beans until tender. Meanwhile, finely chop some onion and sauté with butter till golden over medium heat. Add cream to pan and cook, stirring until thickened. Add paprika, salt and pepper to taste. Pour over cooked beans and toss. Bon appétit!