Posted on: Tuesday May 27, 2025

In many ways, June is a difficult month for Manitoba skywatchers. Sunset is very late as we approach the summer solstice, and the situation is just made worse by daylight savings time which began in March. Even at local midnight (which occurs around 1:30 am CDT for Winnipeg), the sky never gets truly dark from about June 1 to the second week of July – the best we get is “nautical twilight”, which is a deep grey instead of the near-black sky of true night. (Near cities, this effect is usually overwhelmed by light pollution anyway, but it all adds up.)

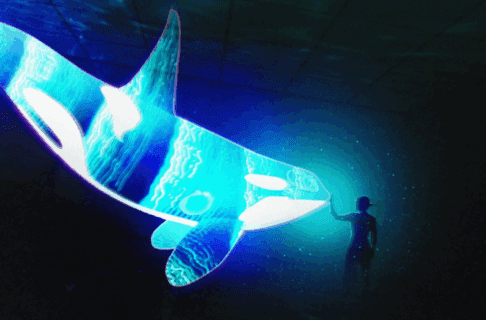

Yet June is the beginning of Milky Way season as well. After midnight the summer constellations are high enough to view, and the brightest part of our Milky Way Galaxy is on full display. You just have to stay up late to see it.

The Solar System for June 2025

Mercury is in the evening sky this month, but angles conspire to keep it too low for easy viewing from Manitoba. Look for it very low in the northwest after sunset. Don’t confuse it with brighter Jupiter, which is descending into the twilight just a few degrees to the left of Mercury.

Venus is very low in the eastern sky just before dawn. It reaches “greatest elongation west” of the sun on June 29, but practically it remains low in the east all month. The crescent moon is nearby on the mornings of June 21 and 22.

Mars is in the constellation Leo, to the lower right of the “sickle” asterism that includes the bright star Regulus. Mars passes within one degree of Regulus on July 16 and 17. The planet and the star will be almost the same brightness, and binoculars will show a nice colour contrast – Mars a ruddy orange, and Regulus a blue-white.

Jupiter fades into the sunset this month, dropping behind the Sun from our point of view. It is in conjunction on June 24-25, passing directly behind the Sun.

Saturn rises about 3 am at the beginning of June, and by 1am at the end of the month. The rings are inclined only a few degrees from our line of sight and we’re seeing the unlit side of them. Neptune is nearby for most of the summer (see below). The last quarter Moon is nearby on the morning of June 19.

Uranus passes behind the Sun as seen from Earth on May 17, and is invisible all month.

Neptune is in the same binocular field of view as Saturn for the entire month, closing to within a degree at the end of June. Too far to see without optical aid, Neptune requires good binoculars or a small telescope to even spot, and a large telescope to make it out as anything more than a faint dot.

Of the five known dwarf planets, only (1) Ceres is close enough to be seen in binoculars or a small telescope. In June, Ceres in below and to the left of Saturn and Neptune; you’ll need a chart like the one in the RASC Observer’s Handbook or an app like Stellarium to track it down. Ceres will be easier to spot in the fall as it gets closer and brighter.

Sky Calendar for June 2025

All times are given in the local time for Manitoba: Central Daylight Time (UTC-5). However, most of these events are visible across Canada at the same local time without adjusting for time zones.

Monday, June 2, 2025: First Quarter Moon

Sunday, June 8, 2025 (evening): Jupiter and Mercury are beside each other low in the northwestern sky after sunset.

Wednesday, June 11, 2025: Full Moon

Monday, June 16, 2025 (evening sky): Mars passes within one degree of the bright star Regulus in Leo.

Wednesday, June 18, 2025: Last Quarter Moon

Friday, June 20, 2025: The Summer Solstice occurs at 9:42 pm Central Daylight, marking the beginning of summer in the northern hemisphere.

Tuesday, June 24, 2025: Jupiter is in superior conjunction, behind the Sun from our point of view on Earth.

Wednesday, June 25, 2025: New Moon

Sunday, June 29, 2025 (morning sky): Saturn is one degree south of Neptune in the morning sky.

Monday, June 30, 2025 (evening sky): The Moon is near Mars in the evening sky.

Monday, May 26, 2025 (evening): New Moon

Outside of the regular events listed above, there are other things we see in the sky that can’t always be predicted in advance.

Aurora borealis, the northern lights, are becoming a more common sight again as the Sun goes through the maximum of its 11-year cycle of activity. Particles from the Sun interact with the Earth’s magnetic field and the high upper atmosphere to create glowing curtains of light around the north (and south) magnetic poles of the planet. Manitoba is well-positioned relative to the north magnetic pole to see these displays often, but they still can’t be forecast very far in advance. A site like Space Weather can provide updates on solar activity and aurora forecasts for the next 48 hours. The best way to see the aurora is to spend a lot of time out under the stars, so that you are there when they occur.,

Random meteors (also known as falling or shooting stars) occur every clear night at the rate of about 5-10 per hour. Most people don’t see them because of light pollution from cities, or because they don’t watch the sky uninterrupted for an hour straight. They happen so quickly that a single glance down at your phone or exposure to light can make you miss one.

Satellites are becoming extremely common sights in the hours after sunset and before dawn. Appearing as a moving star that takes a few minutes to cross the sky, they appear seemingly out of nowhere. These range from the International Space Station and Chinese space station Tianhe, which have people living on them full-time, to remote sensing and spy satellites, to burnt-out rocket parts and dead satellites. These can be predicted in advance (or identified after the fact) using a site like Heavens Above by selecting your location.