Posted on: Friday February 28, 2025

March brings the spring equinox, warmer weather, and the last chance to see the winter constellations. This year, March also hosts a pair of eclipses (one visible from North America) and a planetary line-up that is almost as good as it gets.

![A simulated view of the "parade of planets" on March 2, 2025. [Image: Stellarium]](https://manitobamuseum.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/stellarium-001-e1740764429838.png)

The Solar System

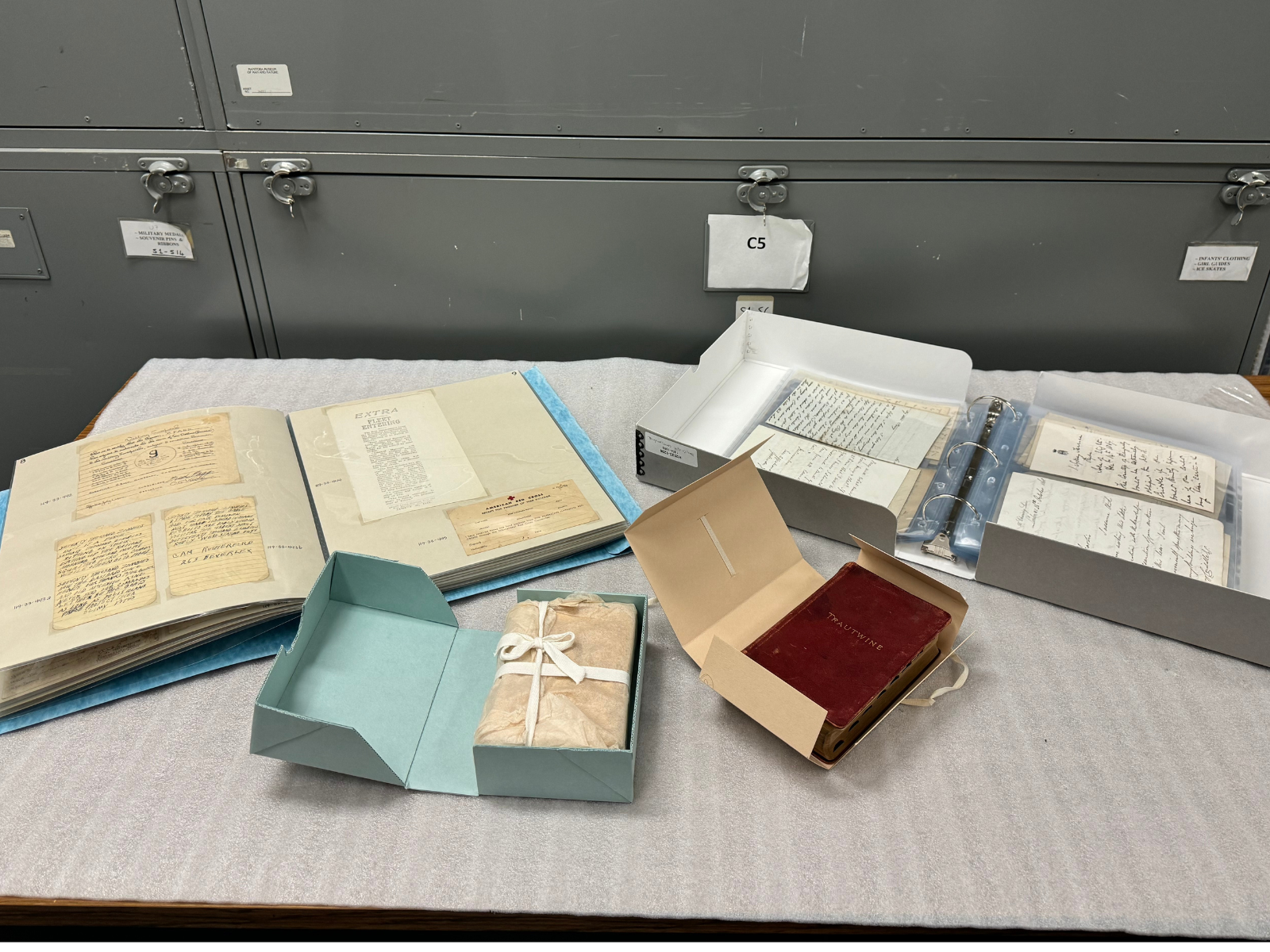

The “Planetary Parade”: While it’s over-hyped online by people who don’t know the sky very well, this month *is* a good time to spot the planets. In late February and early March, we can see 4 of the 5 bright planets at the same time in early evening. But, it isn’t any more spectacular than it has been for the last month – the planets are effectively always in a “parade”, and so if you didn’t notice it in January or February you might wonder what the fuss is all about. That’s social media for you – anything that reliably generates “likes” or “shares” will be used to drive engagement without managing expectations or even providing accurate content.

Bottom line: you can see most of the planets this month, including Mercury which is generally the hardest one to see because it’s so close to the sun. Enjoy the view!

Mercury reaches its best visibility of 2025 this month, rising into the evening sky at the beginning of the month.

Venus still dominates the western sky at sunset at the beginning of March, but it dives towards the Sun by mid-March. For a few days around its closest conjunction to the Sun, it will be visible in both the morning and evening sky at the same time. See the Sky Calendar for details.

Earth reaches the point in its orbit when its poles are perpendicular to its orbital path around the Sun. We call this occurrence the equinox, and this year the Spring Equinox occurs at 4:01 a.m. Central Daylight Time on March 20, 2025. While this marks the astronomical beginning of spring, it has little connection to the weather. The main event is that the hours of daylight and nighttime are equal – equinox means “equal night”. Any stories about being able to balance an egg on its end only during the equinox are false – you can do that any day of the year, if you have the time and patience for it.

Mars is still bright in the evening sky, forming an ever-changing triangle with the bright stars Castor and Pollux in Gemini. The Moon is nearby on the evening of March 8th.

Jupiter still shines brightly in the evening sky, high in the southwest after sunset in the constellations of Taurus.

Saturn drops into the sunset glare early in the month, and is lost to sight. You *might* catch it in binoculars during the first few days of the month below Mercury, if you have a perfectly flat horizon and crystal-clear skies.

Uranus is to the right of Jupiter, but invisible to the unaided eye. A pair of binoculars will show it as a star-like dot among a sea of other star-like dots; you need a detailed finder chart like those in the RASC Observers’ Handbook to track it down.

Neptune, while technically part of the “parade”, is invisible without a telescope at the best of times, and this month is not the best of times. Neptune is near Venus in the bright twilight sky and probably unobservable this month.

Of the five known dwarf planets, none are visible with typical backyard telescopes this month.

Sky Calendar for March 2025

All times are given in the local time for Manitoba: Central Standard Time (CST) before March 9, and Central Daylight Time beginning at 2:00 a.m. on March 9, 2025. However, most of these events are visible across Canada at the same local time without adjusting for time zones.

Saturday, Mar. 1, 2025 (evening): Mercury begins its two-week period of visibility, rising into the evening sky below Venus. The very thin crescent Moon is nearby on March 1, but likely invisible in the bright sky without binoculars or cameras. (For the “young moon” hunters, it’s a 24-hour-old moon at sunset in Manitoba, close to the limit for what is potentially visible. Flat horizons and clear skies are a must!)

Sunday, Mar. 2, 2025 (evening): The crescent Moon is above Venus in the evening sky, visible to the unaided eye and with glorious Earthshine illuminating the dark side. Photo op!

Monday, March 3, 2025 (evening): The crescent Moon is mid-way between Venus and Jupiter, while Mercury continues to rise higher in the west below Venus.

Wednesday, March 5, 2025 (evening): The Moon and Jupiter form a nice grouping with Aldebaran and the Pleiades star cluster this evening.

Thursday, March 6, 2025 (evening sky): The Moon is above Jupiter, high in the southwest in the evening sky.

Saturday, March 8, 2025 (evening): Starting tonight, the planets Mercury and Venus are visible in the same field of view of typical household binoculars (roughly a 7-degree field). They’ll remain this close until Mercury is lost from sight around March 14.

Also tonight, the Moon is just above Mars high in the southeast after sunset, with the two bright stars Castor and Pollux nearby. Over the course of the night you can see the Moon’s orbital motion as it passes Mars and moves farther away. At 8pm CDT the Moon is right above Mars; by 3am CDT it has moved to be mid-way between Mars and Castor.

Finally, unless you’re up all night, set your non-internet clocks ahead one hour before you go to bed. Daylight Savings Time starts tomorrow at 2am (1:59 a.m. Central Standard Time is followed by 3:00 a.m. Central Daylight Time).

Sunday, March 9, 2025 (morning): Daylight Savings Time started this morning.

Tuesday, March 11, 2025 (evening): Mercury reaches its highest point above the horizon, while Venus has sunk down to almost meet it. After tonight both Mercury and Venus will rapidly sink into the sunset glow.

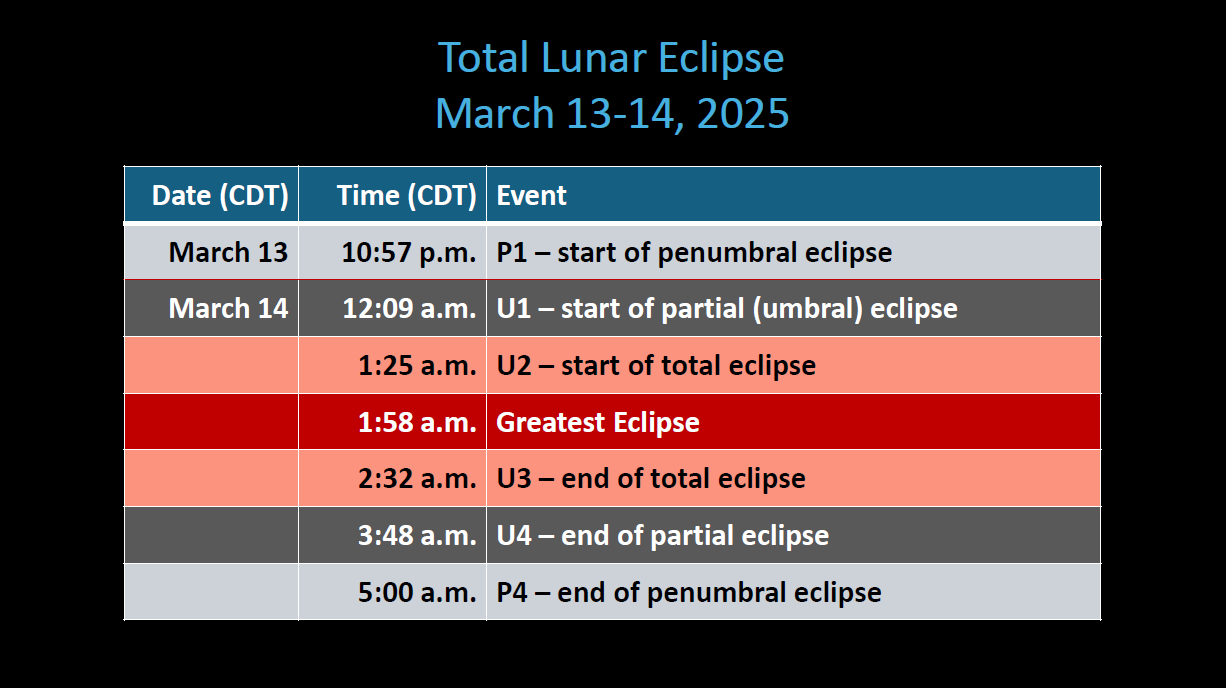

Thursday, March 13 (evening): The total lunar eclipse begins at 10:57 p.m. CDT tonight and extends throughout the night into early Friday morning. Unlike a solar eclipse, a lunar eclipse is absolutely safe to watch.

For local times for other locations across North America, visit the NASA Science Directorate Eclipse Page.

Thursday, March 20, 2025: The Vernal Equinox occurs at 4:01 a.m. Central Daylight Time, marking the beginning of astronomical spring. Also on this date, Venus begins to be visible in both the evening and morning skies (see the entry for March 23 for details).

Sunday, March 23, 2025: The Earth passes through the plane of Saturn’s rings. This would afford a rare view of the rings “disappearing”, but unfortunately Saturn will be too close to the Sun for the event to be easily visible.

Also today, Venus passes between us and the Sun (actually, just “above” the Sun from our point of view). For a few days on either side of this, Venus will be visible in both the evening sky after sunset and the morning sky before sunrise before transitioning into a morning-only object.

Saturday, March 29, 2025: There is a partial solar eclipse on this date, but it is only visible from northeastern Canada, Greenland, Iceland, and northwestern Europe. For details on the view from your location, use this link.

Spring break at the Planetarium: Our spring break programming begins Saturday, March 29 and extends through Sunday, April 6, 2025, open daily from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Our brand new family show, “Voyage of the Stars: A Sea and Space Adventure” premieres, and we’ll also have an encore presentation of “Edge of Darkness”, which takes us among the dwarf planets such as Ceres and Pluto. Advance tickets and showtimes are available here.

Northern Lights, Meteors, and other Cool Stuff

Outside of the regular events listed above, there are other things we see in the sky that can’t always be predicted in advance.

Aurora borealis, the northern lights, are becoming a more common sight again as the Sun goes through the maximum of its 11-year cycle of activity. Particles from the Sun interact with the Earth’s magnetic field and the high upper atmosphere to create glowing curtains of light around the north (and south) magnetic poles of the planet. Manitoba is well-positioned relative to the north magnetic pole to see these displays often, but they still can’t be forecast very far in advance. A site like Space Weather can provide updates on solar activity and aurora forecasts for the next 48 hours. The best way to see the aurora is to spend a lot of time out under the stars, so that you are there when they occur.,

Random meteors (also known as falling or shooting stars) occur every clear night at the rate of about 5-10 per hour. Most people don’t see them because of light pollution from cities, or because they don’t watch the sky uninterrupted for an hour straight. They happen so quickly that a single glance down at your phone or exposure to light can make you miss one.

Satellites are becoming extremely common sights in the hours after sunset and before dawn. Appearing as a moving star that takes a few minutes to cross the sky, they appear seemingly out of nowhere. These range from the International Space Station and Chinese space station Tianhe, which have people living on them full-time, to remote sensing and spy satellites, to burnt-out rocket parts and dead satellites. These can be predicted in advance (or identified after the fact) using a site like Heavens Above by selecting your location.