Posted on: Wednesday November 27, 2024

Winter nights start early and last long, making them perfect for star watching. Except for the temperature… and the clouds… Catch a clear December night, though, and you’ll be treated to the brightest stars and planets in the sky.

Comet Updates

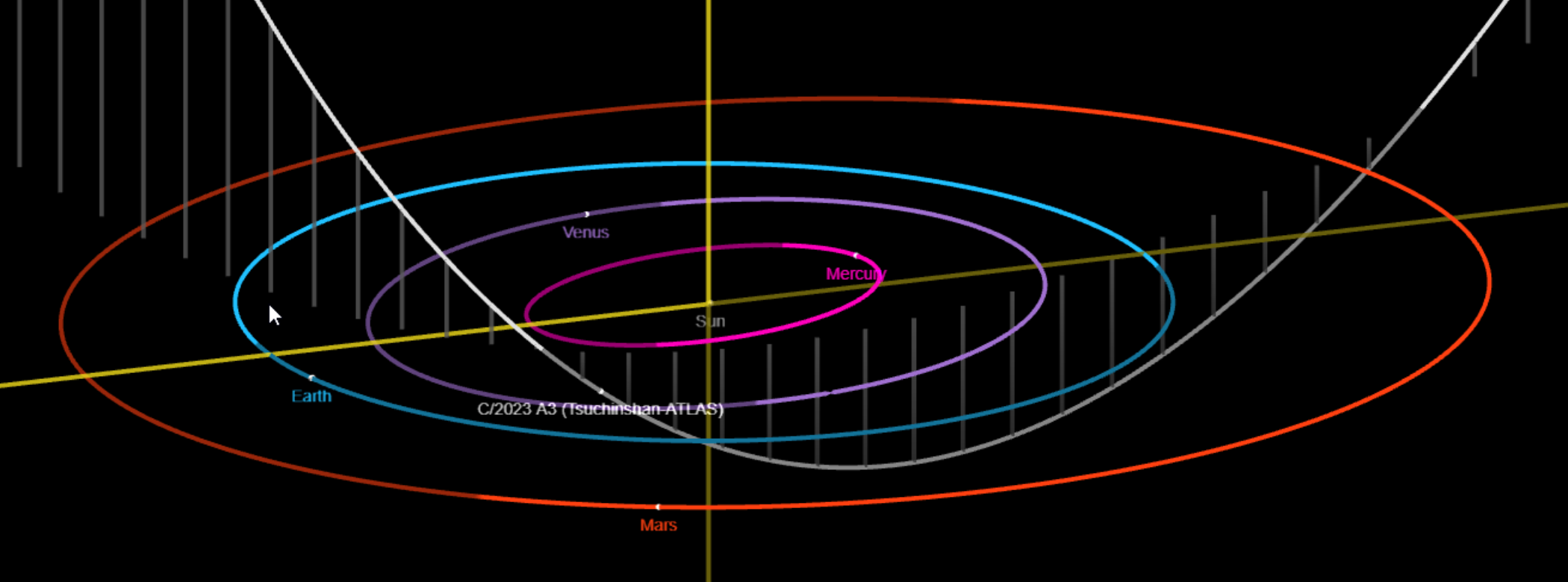

The great fall comet, 2023 A3 (Tsuchinshen-ATLAS) has come and (mostly) gone, providing some beautiful views in October and November. It’s still in the evening sky, but only visible with telescopes as it rockets away from the inner solar system.

Another comet, Comet 2024 G3 (ATLAS), was discovered by the same program that helped find 2023A3 – the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System, or ATLAS. This comet, a so-called “sun-grazer” will likely get quite bright, but only be visible in the daytime sky and from the southern hemisphere, so that means most Manitobans won’t be able to see it.

The Solar System

Mercury passes between Earth and Sun (and slightly above the Sun as viewed from Earth), so it remains invisible until the second half of December, when it appears low in the southeastern sky just before sunrise. On the morning of December 28, the thin crescent Moon is nearby, next to the reddish star Antares.

Venus spends the month in the evening sky, low in the southwest after sunset. The thin crescent Moon approaches on the 3rd, is nearby on the 4th, and is still close on the 5th, making a nice photo op. It stands a little higher at sunset each night, and sets about three hours after sunset. In a telescope, Venus displays phases like the Moon, and in December it is about 50% illuminated, a tiny half-moon shape at high power.

Mars rises in the northeast about 9pm in early December, and a bit after 7pm by month’s end. By midnight it is high in the south, providing the clearest telescope views. Mars reaches its best next month, its closest point to Earth on this orbit, but it’s worth looking at now.

Saturn is low in the south at sunset, and sets before midnight. The rings are nearly edge-on as seen from Earth, but visible in a telescope with more than about 30x magnification. Saturn edges closer to Venus and the setting sun each night, making it lower and harder to get clear telescopic views.

Sky Calendar for December 2024

Dec. 1 : New Moon

Dec. 4: The thin crescent Moon is below Venus, just after sunset, low in the southwestern sky.

Dec. 5: The thin crescent Moon is to the left of Venus in the southwestern sky, just after sunset.

Dec. 7: Jupiter at opposition, visible all night.

Dec. 7: The crescent Moon is below and to the right of Saturn in the evening sky.

Dec. 8: The First Quarter Moon is to the left of Saturn in the evening sky.

Dec. 13-14: Peak of the Geminid meteor shower. The nearyl-full Moon will reduce the number of meteors seen, but you can still expect 20-40 meteors per hour in late evening and early morning.

Dec. 14: The nearly-full Moon forms a line with Jupiter and the bright star Aldebaran in the eastern sky.

Dec. 15: Full Moon

Dec. 17: The waning gibbous Moon is just above Mars as the pair rises in the East about 7:15 p.m. local time.

Dec. 21: The winter solstice occurs at 4:20 a.m. Central Time, marking the beginning of astronomical winter in the northern hemisphere (and the beginning of summer in the southern hemisphere).

Dec. 22: Last Quarter Moon

Dec. 22-23: The peak of the Ursids meteor shower, which radiate from near the North Star. They only produce a few meteors per hour, though.