Posted on: Monday December 5, 2011

By Dr. Graham Young, past Curator of Palaeontology & Geology

Ever since the Museum’s Earth History Gallery opened in the early 1970s, visitors have been struck by the appearance of a giant skeleton near the end of the gallery. Many children (and perhaps more than a few adults) have thought that it is a dinosaur, but it is in fact a mammal from the much more recent past, a replica of the giant ground sloth Megatherium americanum.

Megatherium was a huge ground-dwelling creature, distantly related to the modern tree sloths. Ground sloths were a very successful group, with fossils known from many parts of South and North America (including western Canada), but sadly they disappeared in the Pleistocene megafaunal extinctions, along with other wondrous creatures such as the woolly mammoth and short-faced bear.

The Megatherium (foreground) and glyptodont (background), viewed from the Earth History mezzanine.

There are many different ground sloths known, but Megatherium was the largest, described as “weighing up to eight tons, about as much as an African bull elephant.” It walked on all fours (with a gait similar to that of a giant anteater), but could rise on its hind legs, supported by the huge tail, to browse on the trees that apparently formed the main part of its diet. Our sloth is shown in this sort of pose, though it lacks a tree at present. Although ground sloths lived across both American continents, Megatherium itself is known only from South America.

Our plaster cast of a Megatherium skeleton is, of course, much newer than the Pleistocene. But it is very old in human terms, so remarkably old that it could be considered as an artifact of a long-past scientific age. It is far older than our current Museum building, much older than the first Manitoba Museum that was located in the Winnipeg Auditorium, older than the Manitoba Legislative Building; in fact it is nearly the same age as the Province of Manitoba! The Megatherium and its close colleague the armoured glyptodont have been companions for a century or more, and both arrived at our Museum by a circuitous path.

But let me begin the sloth’s tale at its beginning.

Megatherium is among the best known of ground sloths, with dozens of fossils collected in South America and shipped to Europe from the 18th Century onward. Many specimens apparently came from the banks of the Luján River near Buenos Aires, Argentina, and were in collections and on exhibit in cities such as Paris, Madrid, and London. The first formal scientific description was produced by the great French scientist Georges Cuvier, in 1796. In the 1850s, a young American scientist, Henry Augustus Ward, made a detailed study of Megatherium, visiting collections in Paris and London among many other places. After his return to Rochester, New York, he became a professor at the University of Rochester, but also founded Ward’s Natural Science Establishment, a company that sold scientific specimens, replicas, and materials.

Ward got started on the casting and selling of fossil skeletons very early. His company was among the first to produce casts for sale to the many new natural history museums that were then being developed, and the giant Megatherium was one of his “star attractions.” His catalogue advertised that a full skeleton consisting of 124 different casts could be purchased for $250, “packed not painted” but including a replica tree.

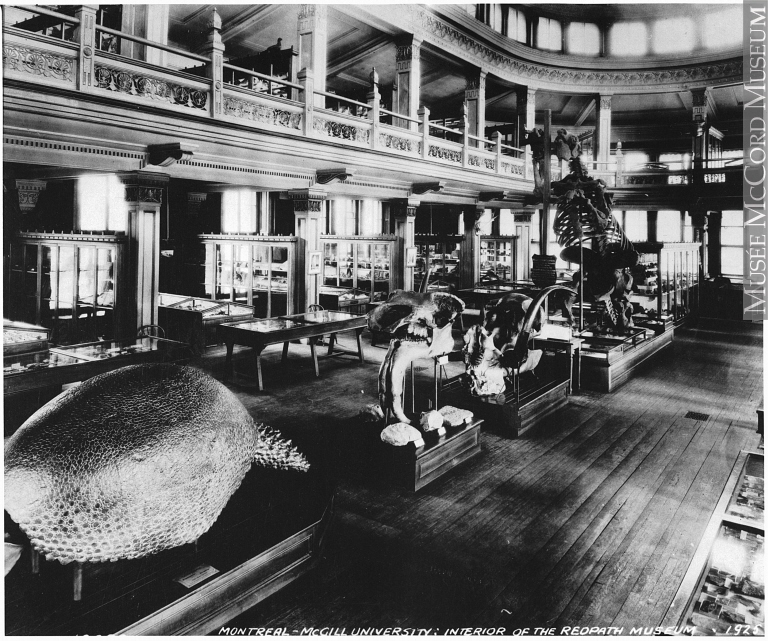

The Redpath Museum c. 1893, with the Megatherium prominently exhibited toward the far end of the gallery. (photo: McCord Museum)

View of the Megatherium from above, c. 1893 (photo: McCord Museum)

In Montreal, a museum for McGill University was planned from the 1860s onward, to exhibit collections developed by the world-famous Professor William Dawson. This facility, funded by and named for the industrialist Peter Redpath, was opened in 1882. It was primarily to serve as a resource for the university’s faculty and students, but secondarily for the education of the people of Montreal.

Dawson had long corresponded with Ward concerning the acquisition of particular items, so it is not surprising that a description of the original museum includes:

“Entering the Redpath Museum, the visitor saw at the back of the ground floor a handsome lecture theater with seats for 200 students… To the right of the entrance, a staircase … led to the main floor or “Great Museum Hall.” Henry Ward’s imposing cast of the British Museum’s megatherium (a giant sloth)–set up by his partner Howell and a status symbol for new museums–distinguished this floor, which displayed paleontological, mineralogical, and geological specimens.”

The Redpath today is a wonderful old-fashioned natural history museum, but it is also rather pocket-sized in comparison with the huge museums of Europe. The Megatherium occupied a considerable proportion of its limited floor space. Several years later, it was joined by the armoured glyptodont, also apparently supplied by Ward’s. Thus, that museum’s main hall was dominated by replicas of giant extinct mammals.

But how did these fascinating and historic replicas become migrants once again, moving westward from Montreal to Winnipeg? In the 1960s there must have been a push to add other creatures such as a dinosaur to the Redpath’s exhibits, and the only way to do this was to replace the large pieces that filled its space (that part of the Redpath is now occupied by a tyrannosaurid dinosaur, among other exhibits).

Image: The Redpath in 1925, showing both the glyptodont and the Megatherium. (photo: McCord Museum)

But how did these fascinating and historic replicas become migrants once again, moving westward from Montreal to Winnipeg? In the 1960s there must have been a push to add other creatures such as a dinosaur to the Redpath’s exhibits, and the only way to do this was to replace the large pieces that filled its space (that part of the Redpath is now occupied by a tyrannosaurid dinosaur, among other exhibits).

According to what my predecessor Dr. George Lammers told me, the Redpath was looking for a home for these enormous casts, and this just happened to come at a time when The Manitoba Museum was constructing its new building, with plenty of square footage that needed to be filled. So the skeleton casts were transferred to our Museum, and they were crated and shipped to Manitoba.

On arrival at the Museum, the replicas were uncrated and examined. George told me that some repair was required as a result of damage in transit, and apparently the plaster bones were found to be stuffed with Reconstruction Era American newspapers! The Megatherium was re-mounted in a slightly different posture, and sadly lacks the “tree” on which it had appeared to browse for ninety years or so. But at least it had its friend, the glyptodont, nearby, and they seem to have happily settled into their new home, impressing (and sometimes scaring) the millions of children who have visited our Museum in the past forty years.

Image: The disassembled Megatherium, after uncrating but prior to assembly in the as-yet unfinished Earth History Gallery space.

On arrival at the Museum, the replicas were uncrated and examined. George told me that some repair was required as a result of damage in transit, and apparently the plaster bones were found to be stuffed with Reconstruction Era American newspapers! The Megatherium was re-mounted in a slightly different posture, and sadly lacks the “tree” on which it had appeared to browse for ninety years or so. But at least it had its friend, the glyptodont, nearby, and they seem to have happily settled into their new home, impressing (and sometimes scaring) the millions of children who have visited our Museum in the past forty years.

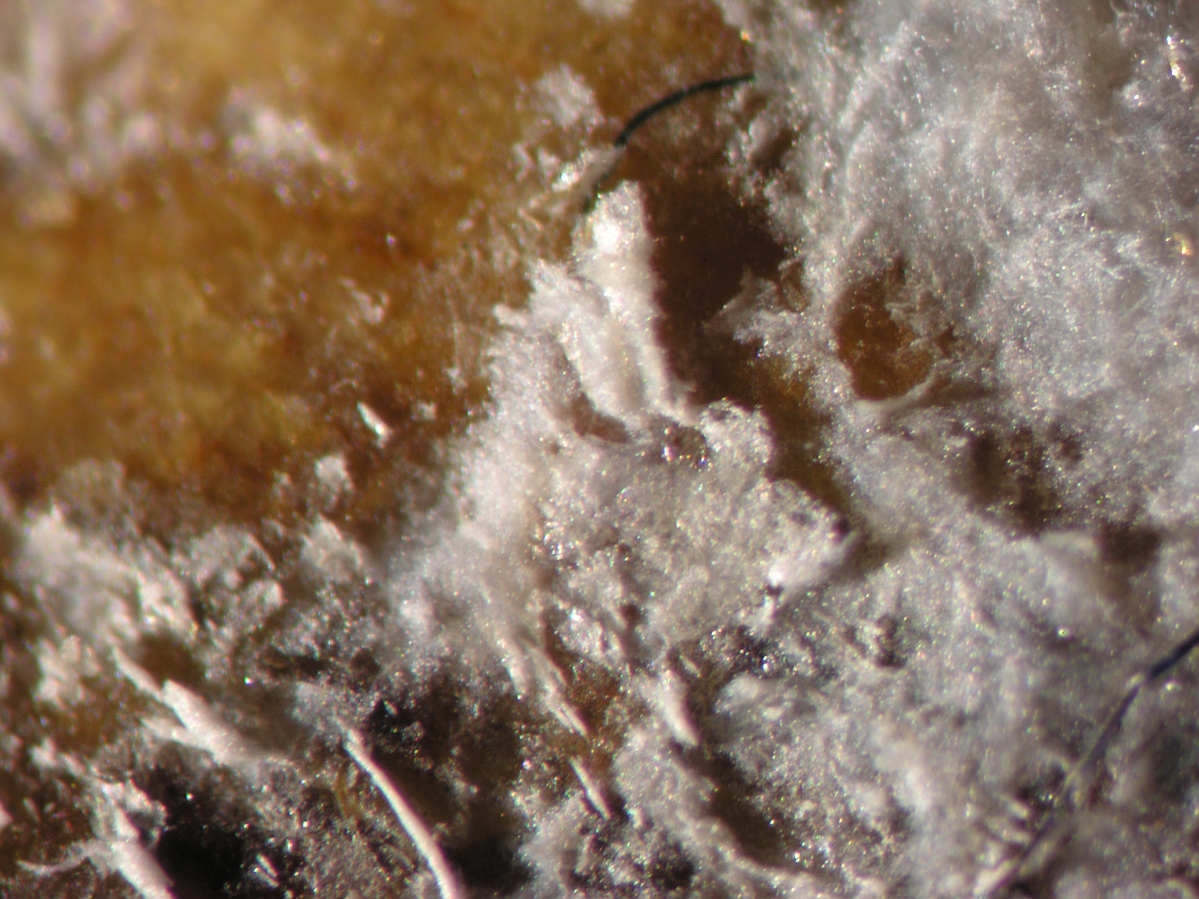

The glyptodont (above) and a detail of the bony plates that made up its protective shell (replica, in our example). Although it looks quite turtle-like, this creature was a mammal related to anteaters, sloths, and armadillos!

The glyptodont. Although it looks quite turtle-like, this creature was a mammal related to anteaters, sloths, and armadillos!

Detail of the bony plates that made up its protective shell (replica, in our example).

The name of our sloth is a bit complicated. The note that George left me calls it Megatherium cuvieri. This is what Ward had called it, and it was probably labelled as such when on exhibit at the Redpath. The species name “cuvieri” was, however, apparently based on a misguided attempt in the 1820s to re-brand Cuvier’s perfectly valid Megatherium americanum. Modern rules of taxonomic usage consider cuvieri to be a nomen illegitimum (“illegitimate name”), so we can safely call it M. americanum.

The sloth’s massive ribcage.

The sloth’s tail (of course!).

Given this cast’s critical role in the history of exhibits at two of Canada’s most important natural history museums, and its place in the story of the development of North American paleontology, what is the future of our sloth? Since we have been progressing with a gradual refurbishment of the Earth History Gallery, I would like to soon plan new interpretive materials that explain the tremendous story and significance of this exhibit. But in the somewhat longer term, wouldn’t it be wonderful if it could be re-mounted and given back its “tree,” perhaps serving a new role as the centrepiece for a larger exhibit of extinct ice age animals?