By Maureen Matthews, past Curator of Anthropology

What is the Berens Family Collection?

Through the generosity of many community leaders, The Manitoba Museum has recently acquired historically significant artefacts that are currently on display in our Foyer area:

- Chief’s Treaty Medal No. 5 and Chain, given to Chief Jacob Berens at the signing of Treaty No. 5, September 20, 1875 (H4-2-212 A, B).

- Chief’s 1901 Commemorative Medal and Ribbon, given to Chief Jacob Berens in 1901, in commemoration of Treaty No. 5, by the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York, later King George VI and Queen Mary, as part of a cross-Canada rail journey (H4-2-213 A, B).

- Chief’s coat, early 20th century, red wool with gold trim, epaulettes, and buttons which read “Dominion of Canada Indians,” belonged to Chief William Berens, the son of Jacob Berens; pants, navy wool

Who is Chief Jacob Berens?

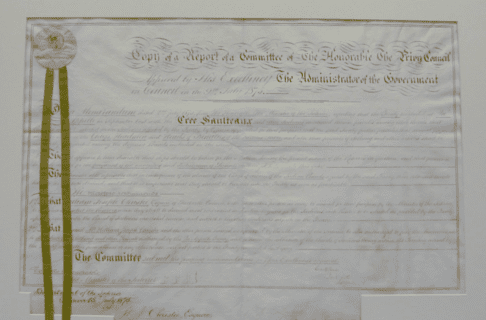

Chief Jacob Berens’ Anishinaabe name, Naawigiizhigweyaash which means ‘light moving in the centre of the sky,’ may indicate that he was born the year of the passing of Halley’s comet, 1835, but his birth date is uncertain (appx. 1932-35). He was the son of Makwa ( Bear), and Aamoo (Bee or Victoria) of Berens River. He married Mary McKay the daughter of the HBC clerk, William McKay in 1862 and they had at least 8 children. On Sept 20, 1875 at Berens River , Jacob signed Treat No. 5 on behalf of the people in the Manitoba communities of Berens River, Poplar River, Bloodvein, Little Grand Rapids, and Pauingassi and the Ontario communities of Poplar Hill and Pikanguikum. He was the Chief of this vast area until his death July 7, 1916.

Who is Chief William Berens?

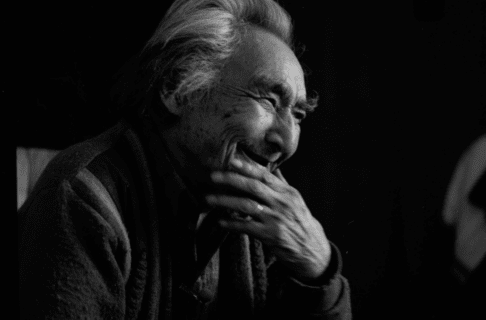

Chief William Berens was the son of Jacob Berens and Mary (McKay) Berens. William was born in 1866He grew up in the Berens River area and in 1917 he succeeded his father as Chief of the Berens River Band, still encompassing the vast territory of the upper Berens River. In later years he became the friend and colleague of the American Anthropologist, A Irving Hallowell, who took down Berens’ reminiscences of the first forty years of his life and recorded many legends and stories – now published by Drs. Jennifer S.H. Brown and Susan Elaine Gray (Memories, Myths and Dreams of an Ojibwe Leader. McGill Queens University Press 2009). William Berens married Nancy (Everett) Berens of Berens River. They had 7 children and were the adoptive parents of several more. William Berens was Chief of the Berens River Band until he died on August 23rd, 1947.

How did the Berens Family Collection come to the Manitoba Museum?

The Berens family Collection came to the museum via a great-great-grandson of Chief William Berens. This young man, another Bill Berens, first contacted the museum in October 2011. Before Christmas of 2011, he brought the two coats, the pants and the two medals to the museum for safekeeping as well as conservation and assessment. As the museum has no acquisitions budget, we turned to the community of Winnipeg and five generous individuals and foundations donated the necessary funds (most wish to remain anonymous). The collection is now on display in a New Acquisitions Case in the foyer of the museum and will be there until May 2013. For the duration of this display we have also borrowed portraits of William Berens and Jacob Berens by Marion Nelson Hooker and we are very grateful to the Winnipeg Art Gallery and the Public Archives of Manitoba for their cooperation in bringing the paintings, the coats and the medals together.

Are you sure the coats and medals are real?

The provenance, the history of ownership, for the collection is very convincing. The Treaty signing Sept 20, 1875 is a matter of record and the Berens family has been carefully looking after the coats and the medals ever since. The medals are exactly as you would expect and have the appropriate Treaty number stamped on them. The Manitoba Museum owns a replica of the Treaty No. 1 medal but the Berens medal is the only original medal from any of the numbered Treaties signed in Manitoba in the collection. The medals and coats were cared for by Bill Berens grandmother, Mary Rose Berens, the wife of Bill Berens Jr. the last Berens’ Chief and the last person to wear the red coat for official functions. The red coat is typical of those given at the time; the buttons have a crown, V.R. indicating Queen Victoria and an array of arrows, a bow and a tomahawk and are stamped with the words “DOMINION OF CANADA INDIAN.” The paintings also help to confirm the authenticity of the collection. The portrait of Chief Jacob Berens wearing a blue Chief’s coat and the two medals was painted by Marion Nelson Hooker in Berens River in 1910. Chief William Berens sat for his painting wearing the red jacket, blue pants and both medals, at her studio in Selkirk in 1930.

An additional portrait, now owned by Matilda Gibb another great, great- grandchild of William Berens, was painted of William Berens wearing the red coat, blue pants and both medals in 1922 by another artist, Lars Haukaness, a teacher at the Winnipeg School of Art who went on the found the Art School at the University of Alberta.

The blue coat in this collection is from the early to mid 20th century. We have a photograph of Chief William Berens wearing it just before he passed away (1947). The contents of his pockets includes notes about appointments to see the Indian Agent in Selkirk and serve to remind us that William Berens was an activist on behalf of his people. He succeeded in getting aboriginal fishery quota and licenses so Treaty fishers could sell in their own right rather than working for a middleman. He was one of the most important political figures in the early history of Manitoba and the Chief during one of the most coercive periods of the Department of Indian Affair’s history.

We also have Chief William Berens’ memories of the signing of the Treaty in Berens River, Sept 20th, when he was a child. This vivid bit of history was recorded by the American anthropologist, A. Irving Hallowell who worked with Chief William Berens throughout the 1930s. Chief Berens remembered the excitement as people gathered for the negotiations but said that the Treaty negotiations dragged on and he was asleep when his father finally came home: