Posted on: Thursday November 18, 2021

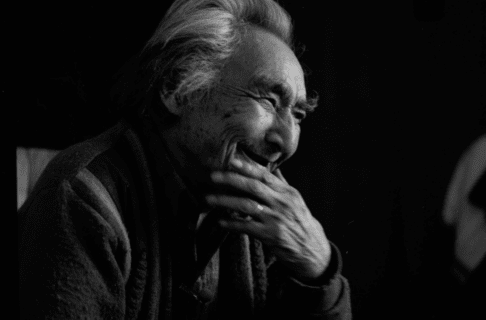

This last summer the Museum installed a new permanent exhibit about William Beal in our Parklands Gallery. Beal was a settler from Minneapolis who arrived in the Swan River Valley north of Duck Mountain in 1906, and homesteaded in the Big Woody district.

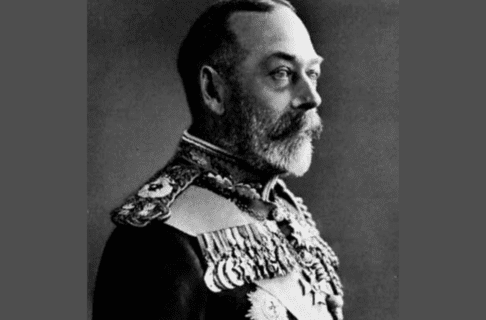

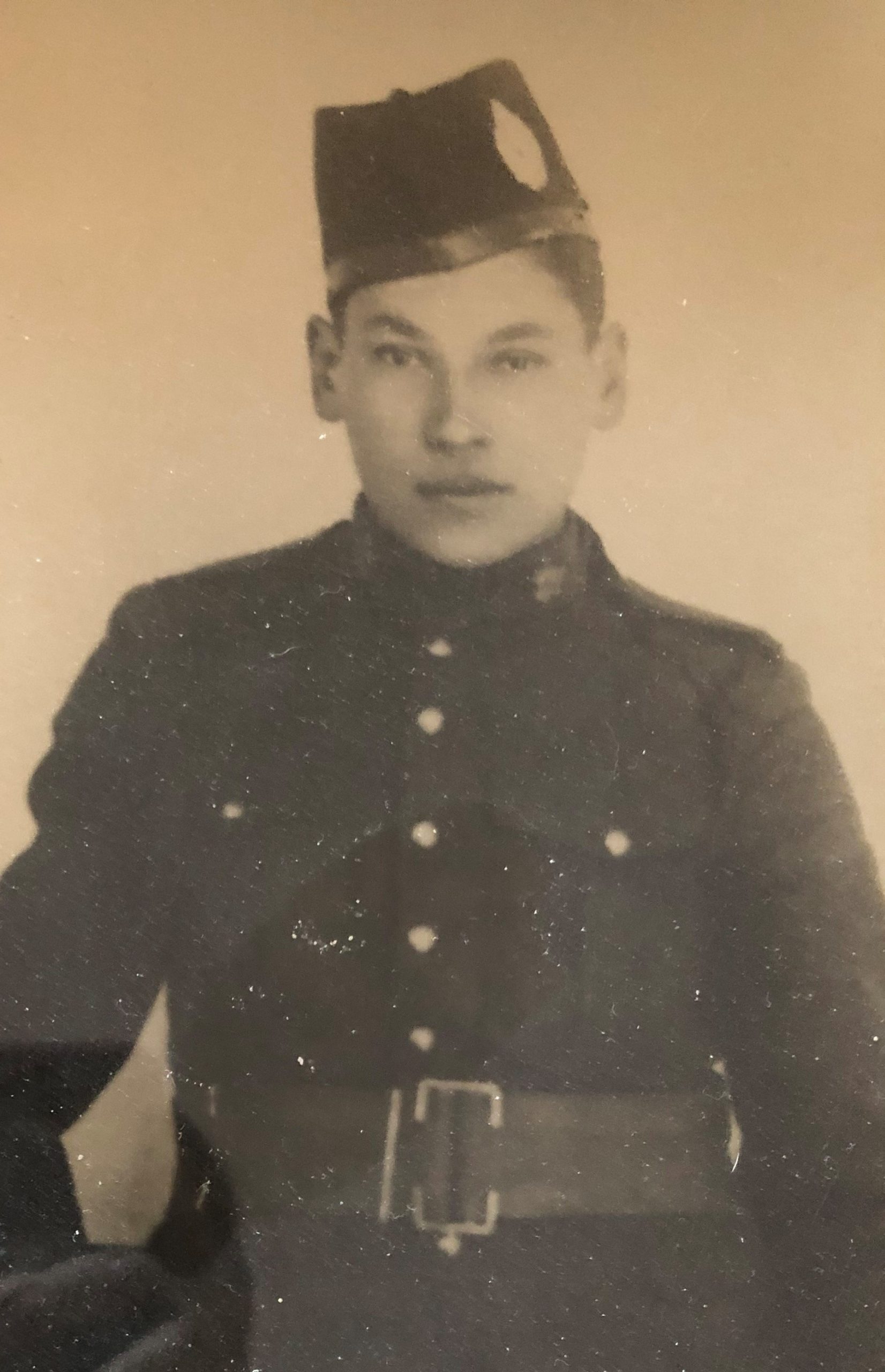

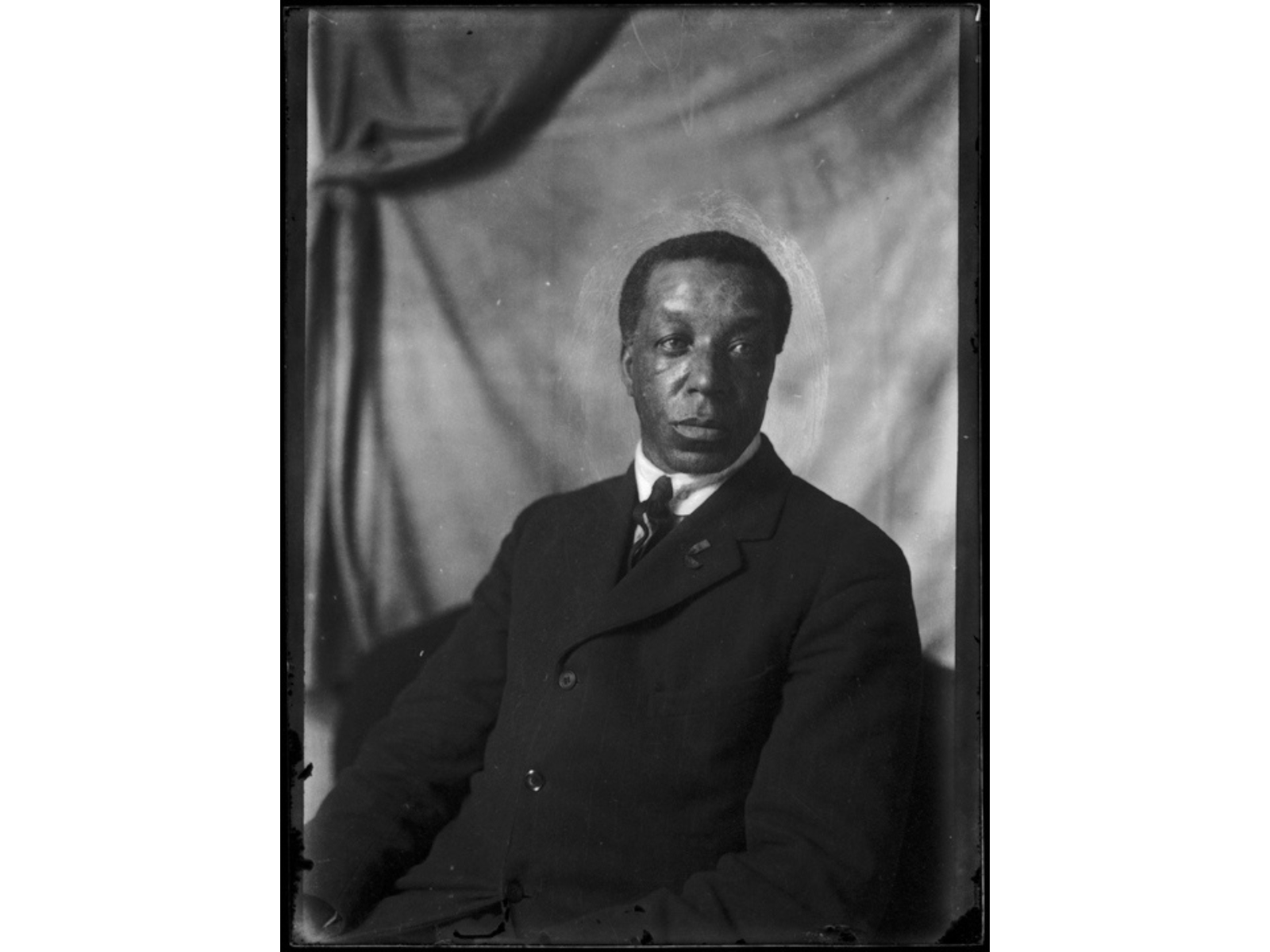

William Sylvester Alpheus Beal (1874-1968) is best known now as a photographer, and left behind dozens of high quality images of his fellow settlers in the region. But Beal was much more than a photographer – he was the “Renaissance Man” of Swan River, a true intellectual. Besides having his own photo studio, he was a professional steam engineer and oversaw engines at various logging operations.

Image: William Beal, self-portrait, Swan River, Manitoba, circa 1918.

He was also an amateur astronomer and constructed his own telescope; he formed a literary and theatrical society, and organized musical recitals; he organized and served on the local school board for 37 years; he was an assistant to the local doctor, providing a type of vaccine injection to locals during the 1918 Influenza pandemic; he was an electrician and fine carpenter; and he was renowned for owning a vast library. Evidently the only thing that didn’t interest him was farming, but he nevertheless cleared land, harvested crops, and received his full homestead grant.

Black Settlers in Manitoba

The racism William Beal experienced in the United States denied him his chance of becoming a medical doctor. Though he formed close friendships in the Big Woody district, he was the only Black man in the area, and experienced racism there as well.

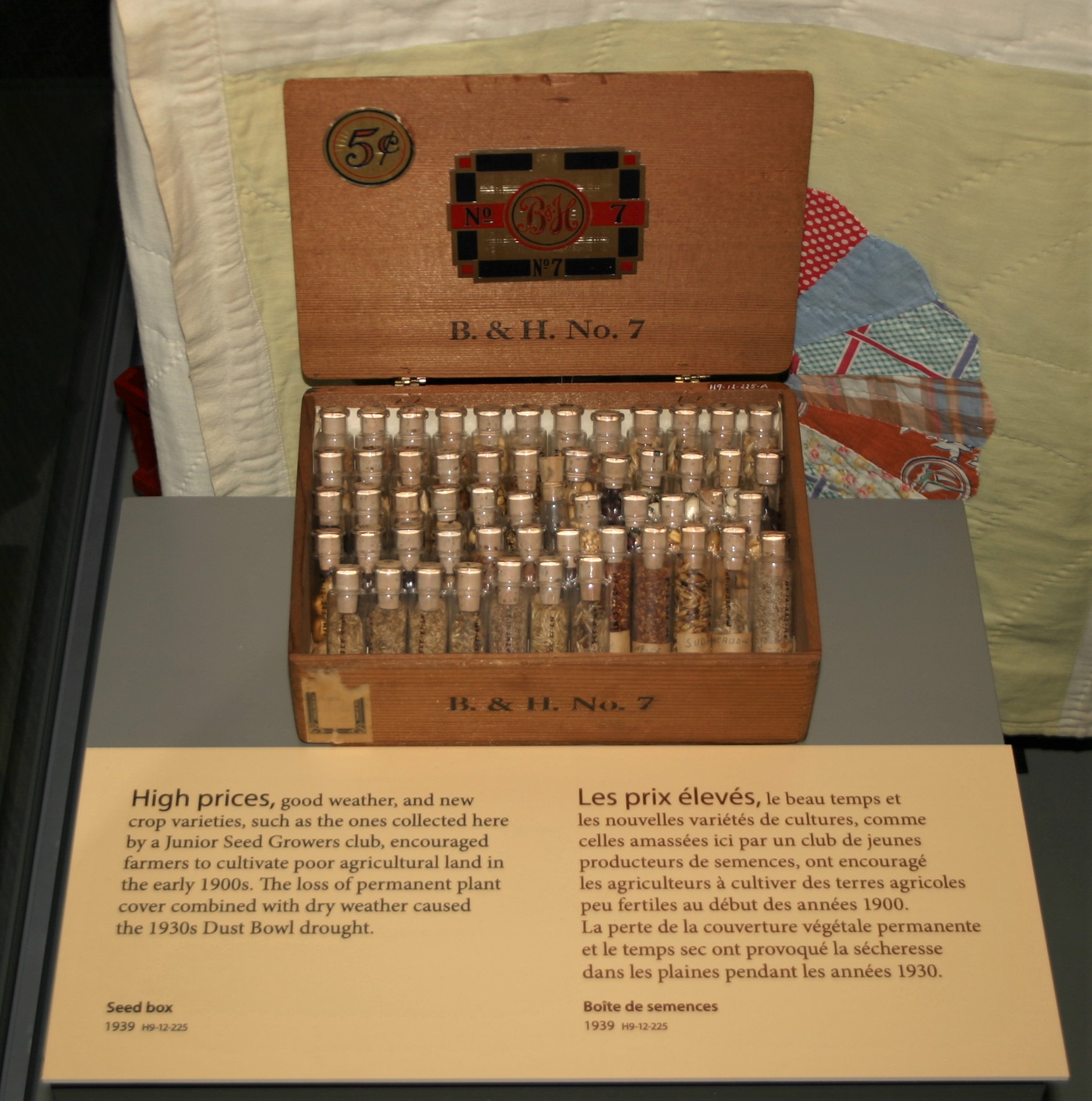

In the early 1900s the Canadian government actively prevented immigration of Black people to Canada, through misinformation campaigns, bribery of officials, and arbitrary requirements not asked of white immigrants. In 1911, 200 Black farmers from Oklahoma were finally able to enter Manitoba at Emerson, after a rigorous and delayed inspection. It’s not known what hurdles Beal faced when entering Manitoba back in 1906, but after he settled in Big Woody district, he was there to stay, and contributed so much to the local community. He passed away in 1968 at the age of 94.

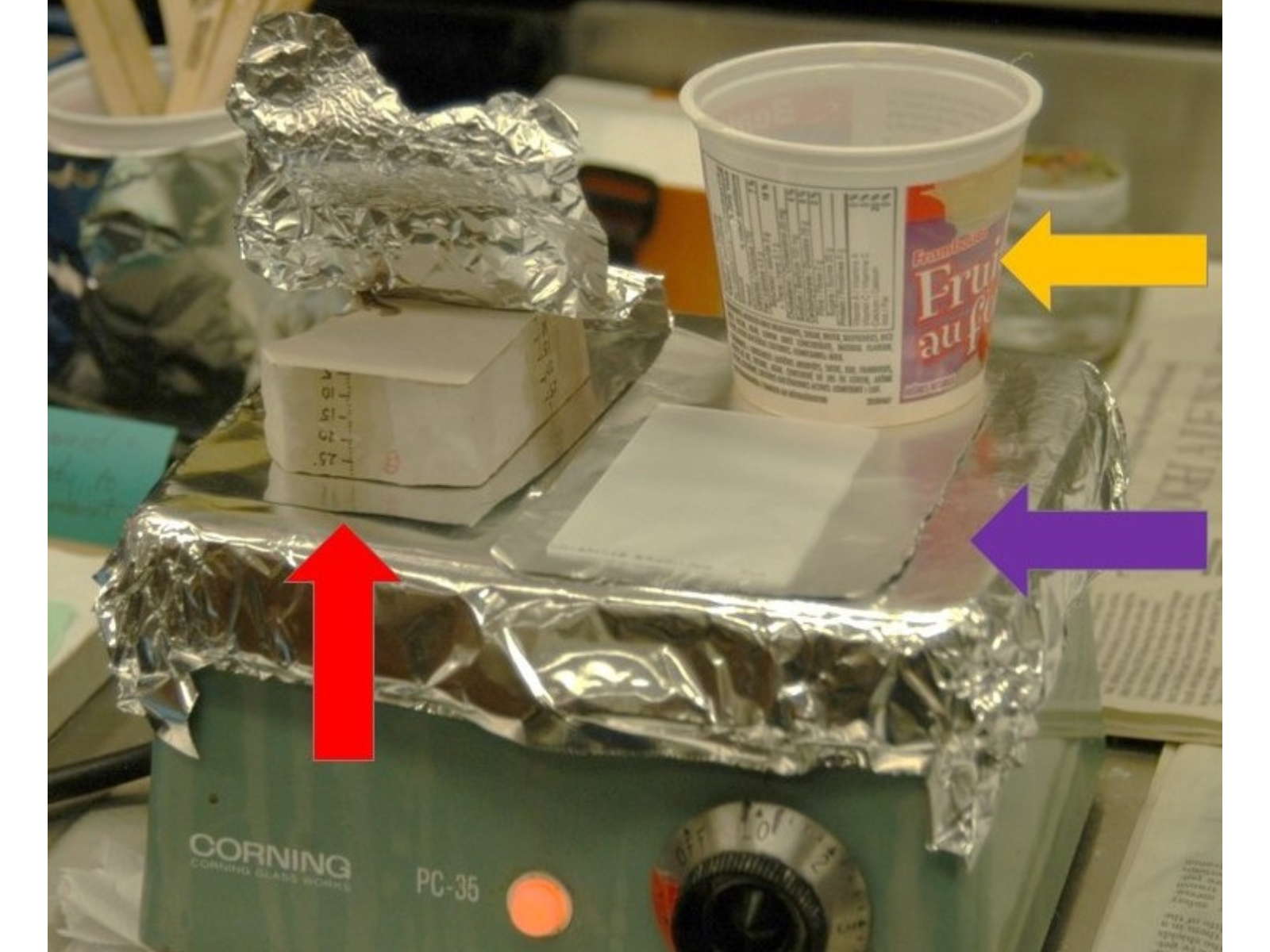

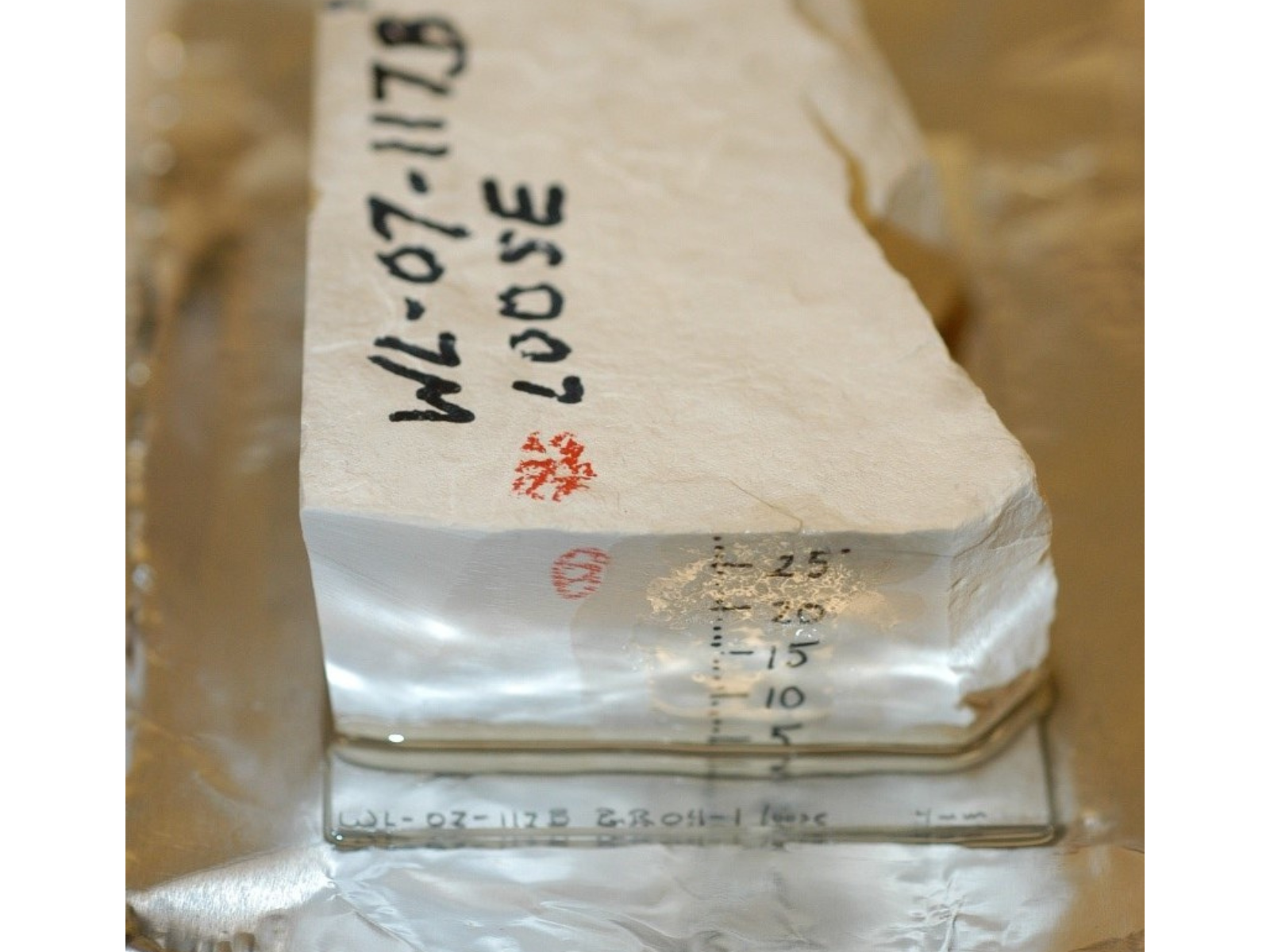

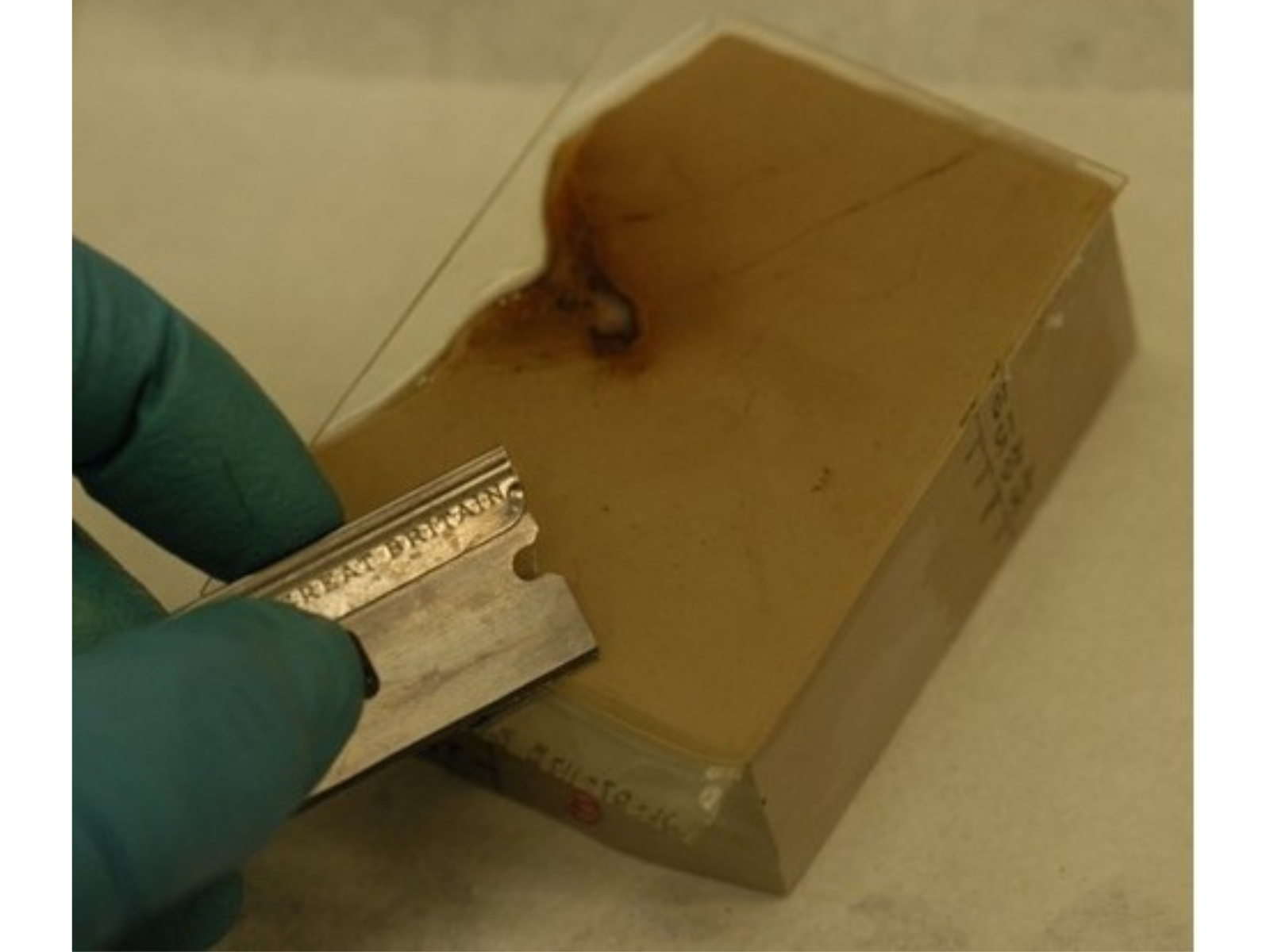

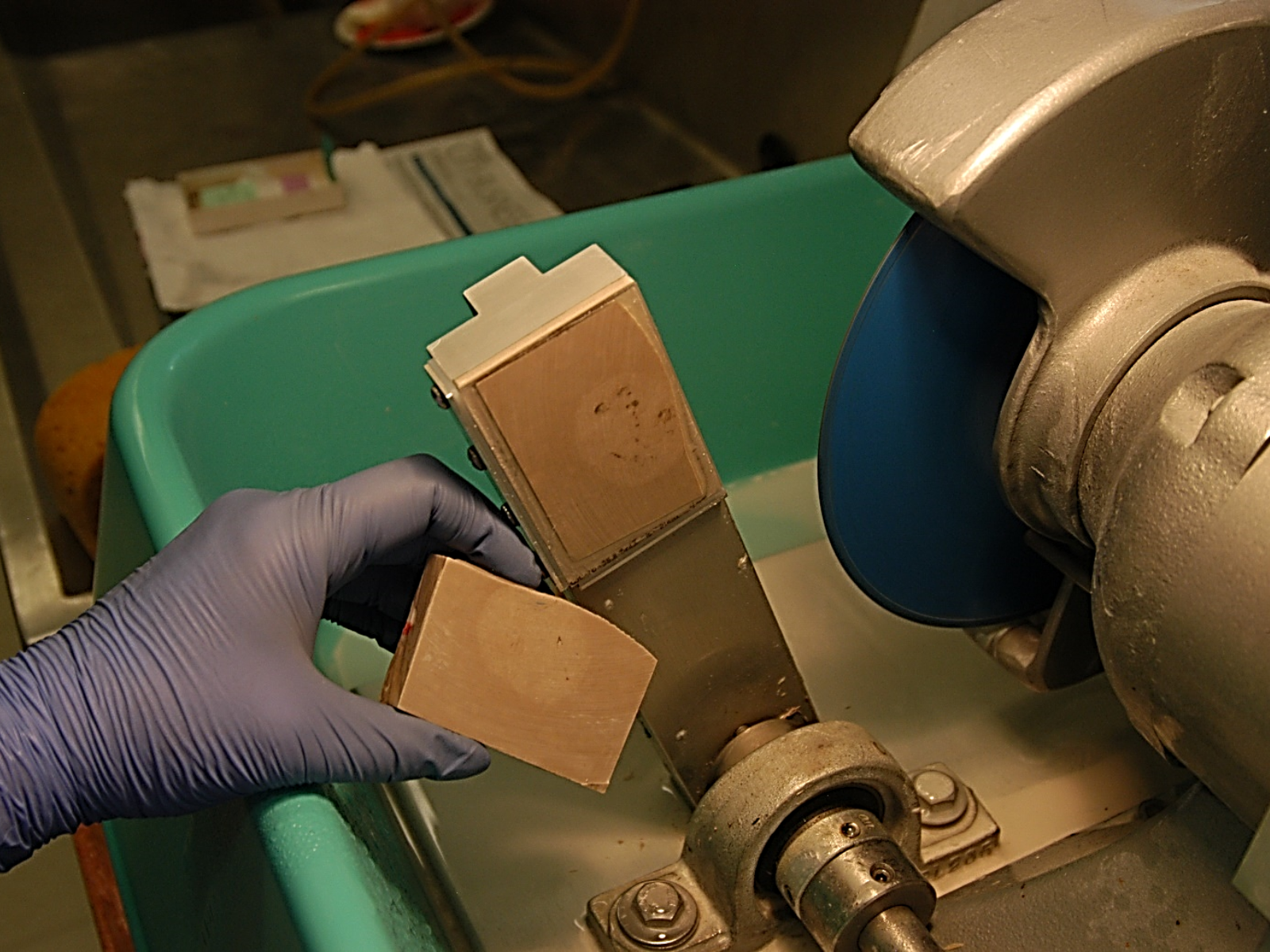

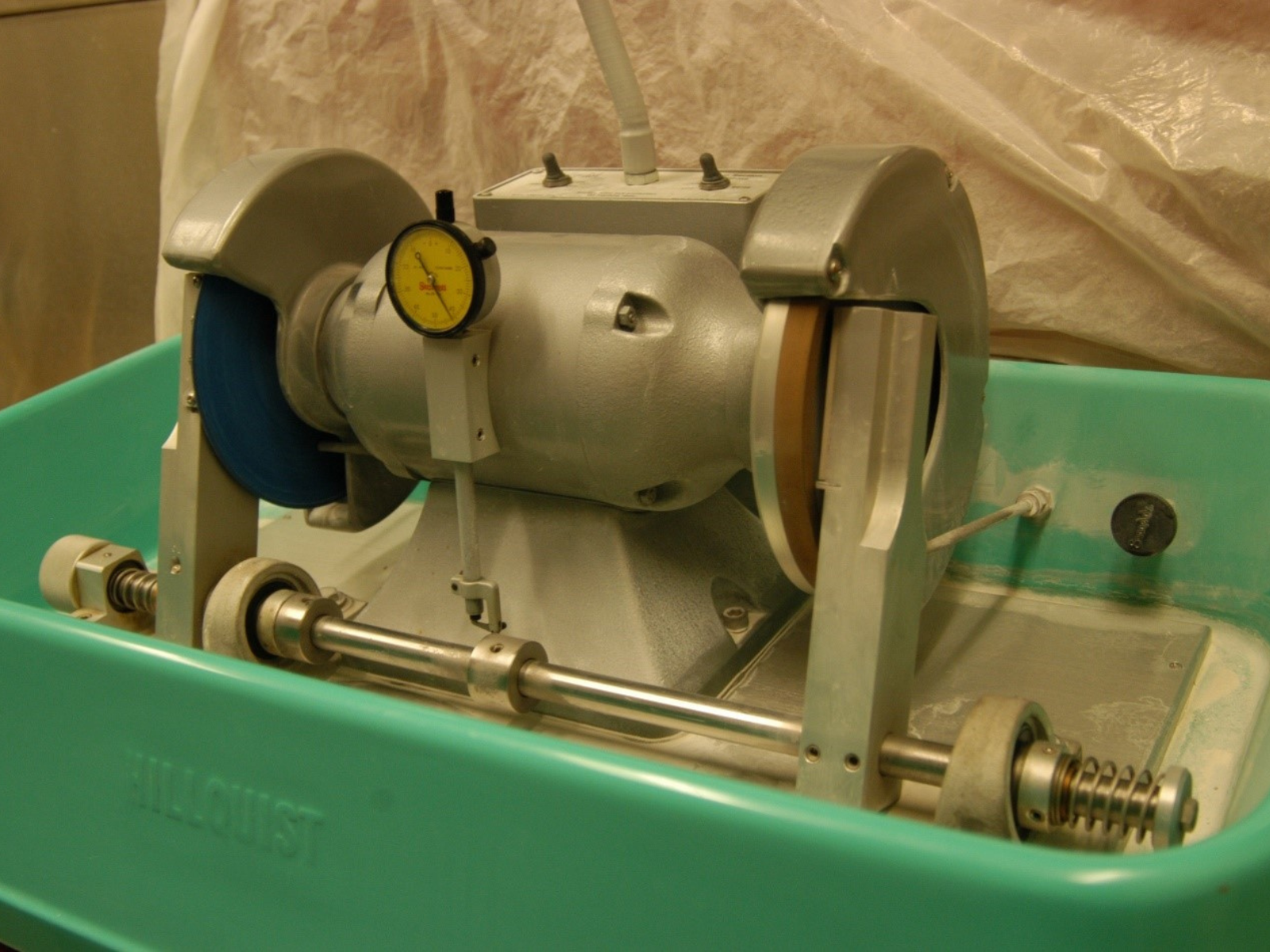

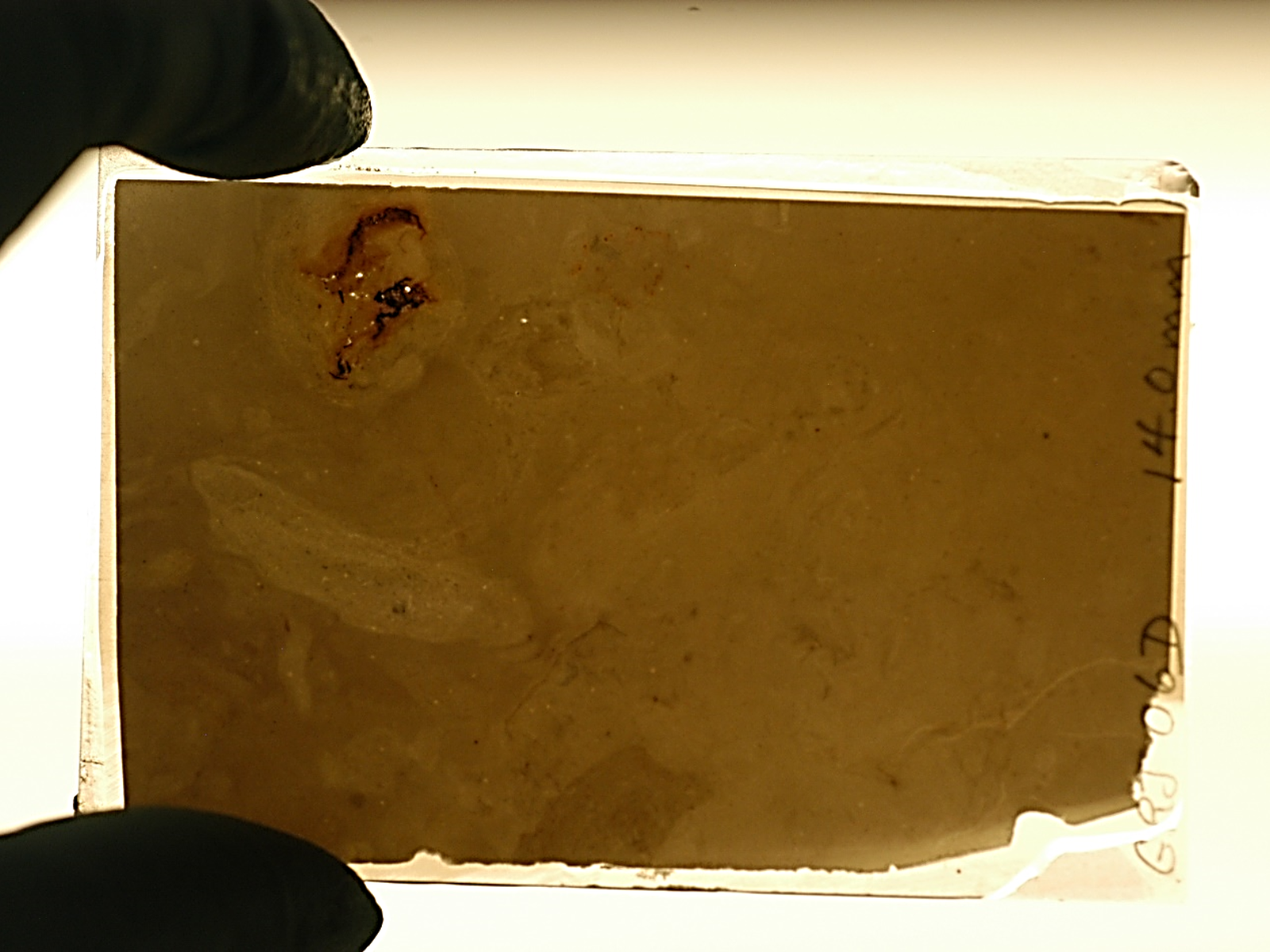

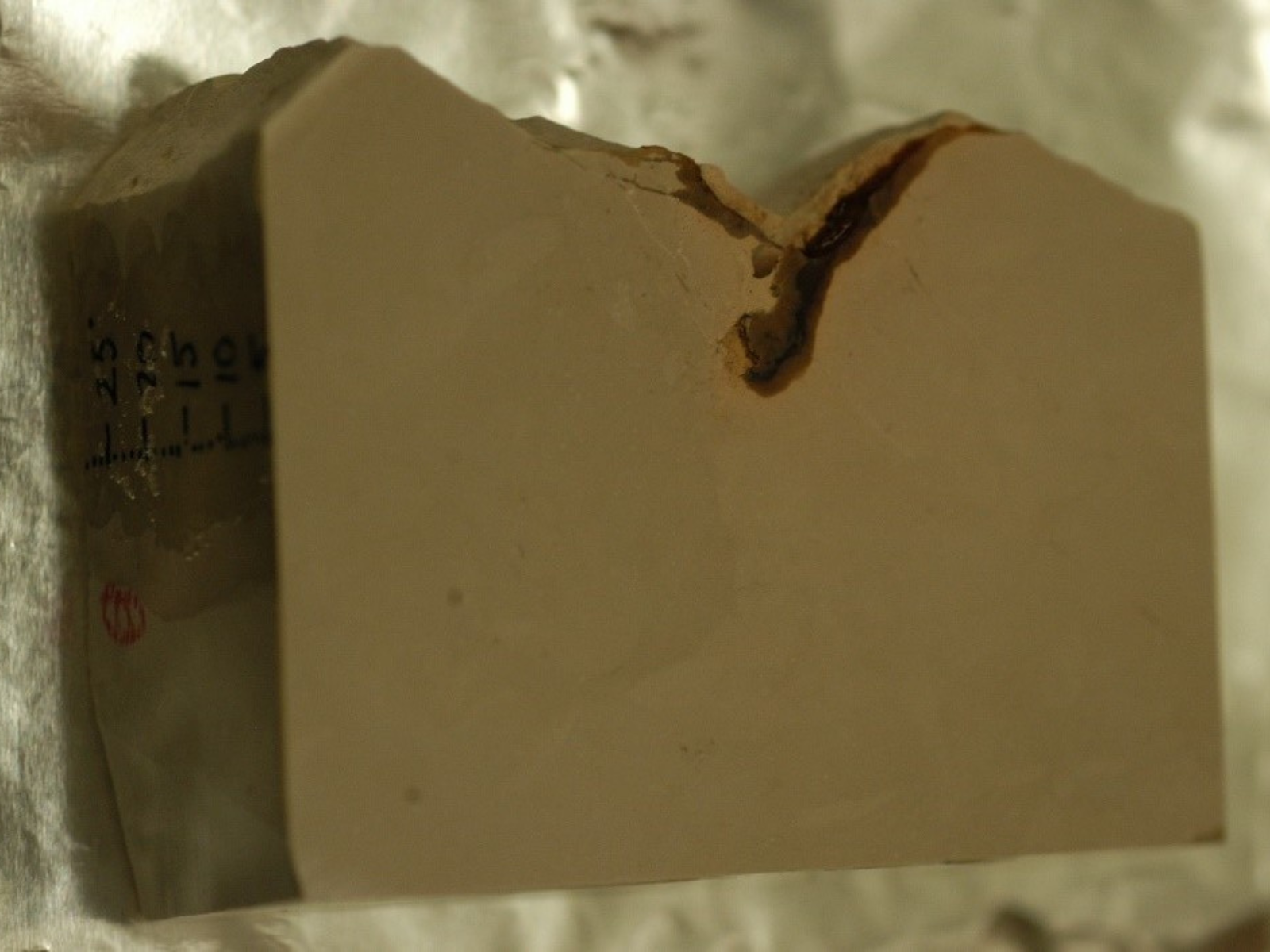

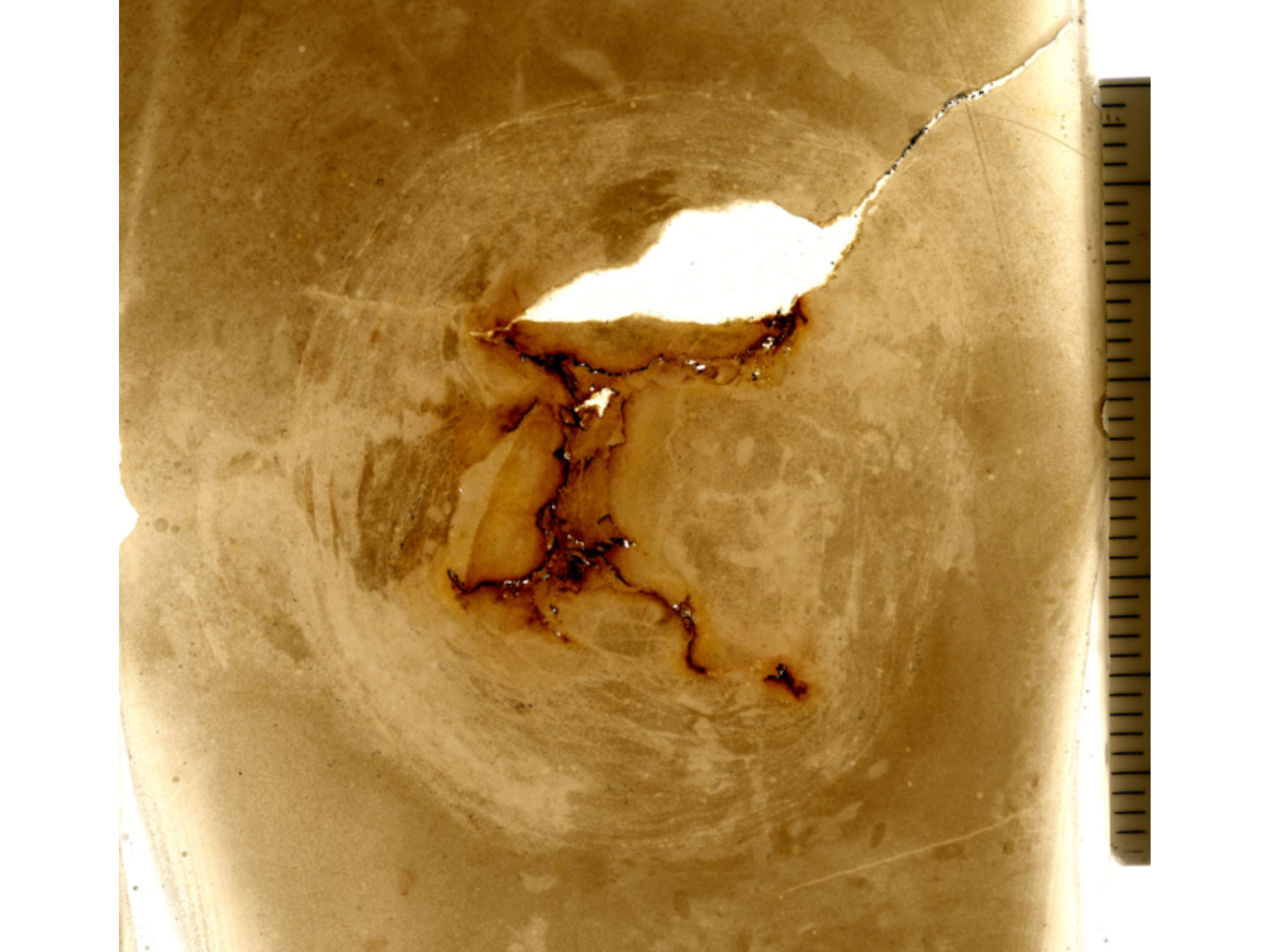

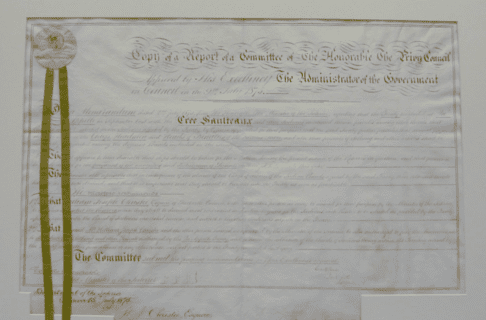

William Beal used a camera like this one to photograph the people of Swan River Valley. He developed the 5 X 7 inch glass negatives in his own studio using chemical mixtures. Eastman Kodak camera, circa 1903, and chemical bottles. H9-5-716A. Copyright Manitoba Museum.

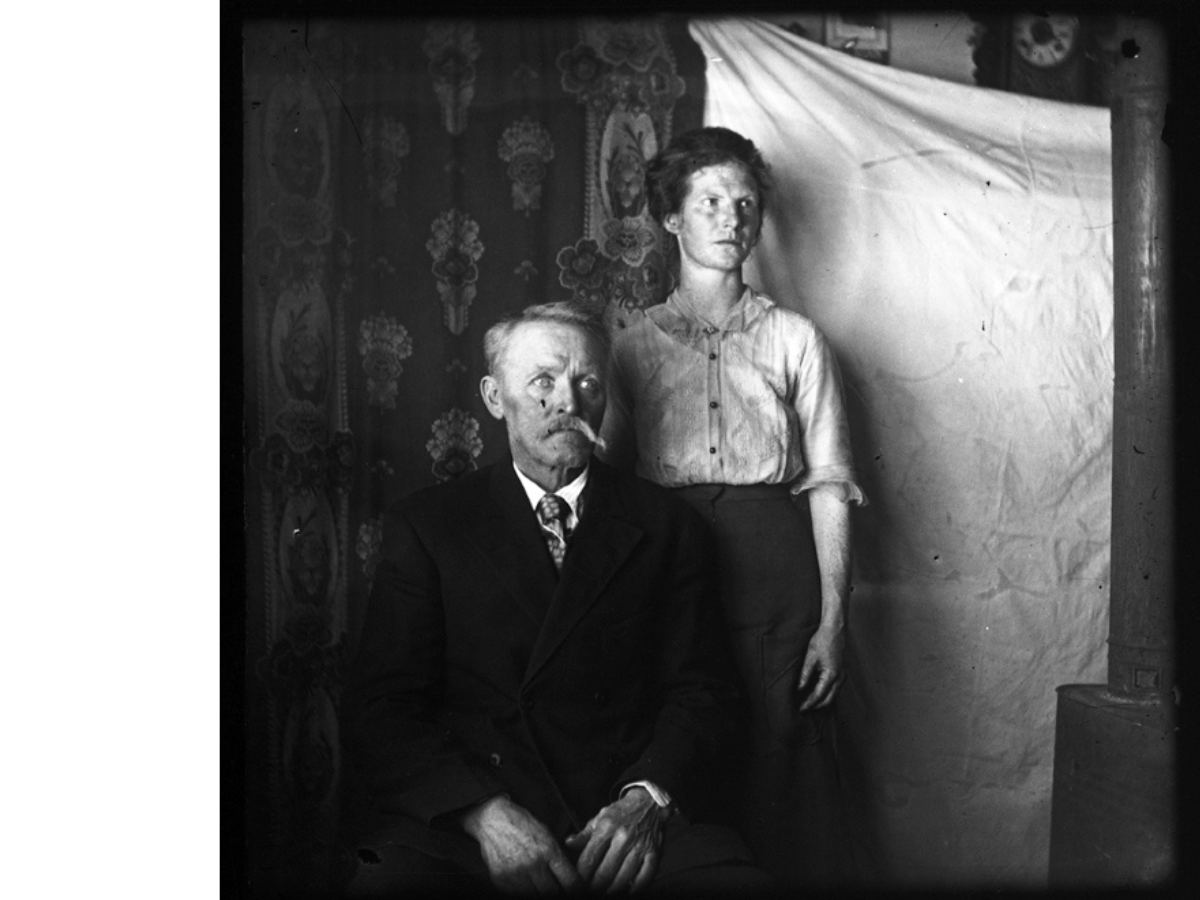

Abe and Dora Hanson, Big Woody district, Swan River MB c. 1917. Photo by William Beal.

Percy and Emma Potten with children, Evelyn and Bert, Big Woody district, Swan River MB 1915. Photo by William Beal.

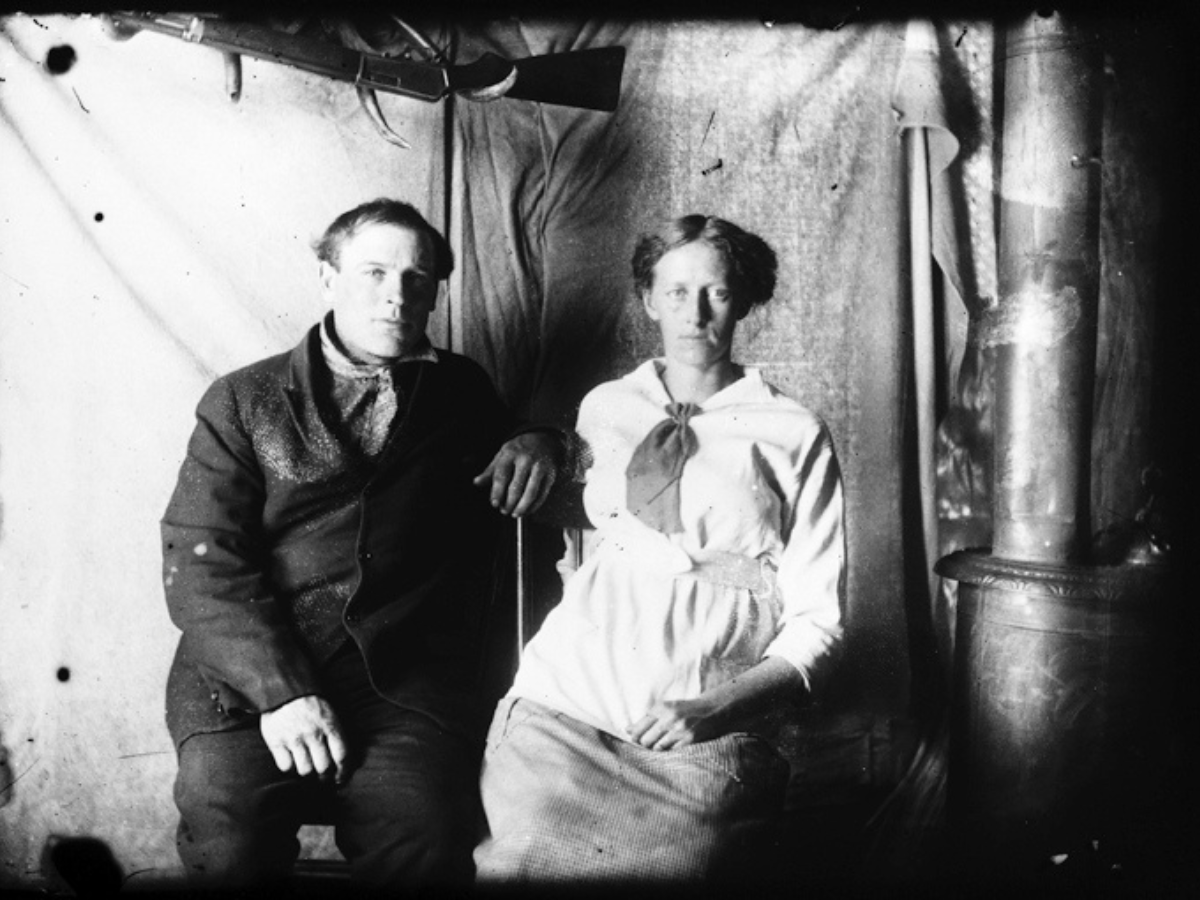

Roy and Hilda Sedore, Big Woody district, Swan River MB c. 1916. Photo by William Beal.

Billy: The Life and Photography of William S. A. Beal, was published in 1988 by Leigh Hambly and Rob Barrows, a former Manitoba Museum photographer who grew up in the Swan River Valley. It features detailed research on Beal’s life and many of his photographs.