Posted on: Monday September 17, 2018

By Matthew Gowdar, Collections and Conservation Assistant

This summer, I was given the amazing opportunity to work at the Manitoba Museum through the Young Canada Woks program. From the end of May until mid-August, I held the full-time position of Collections and Conservation Assistant.

While this was not my first experience working at a museum or archive, the Manitoba Museum was certainly a step up for me, in terms of scale. As a History major at the University of Manitoba, this opportunity was especially exciting, as it fell directly within my field of study.

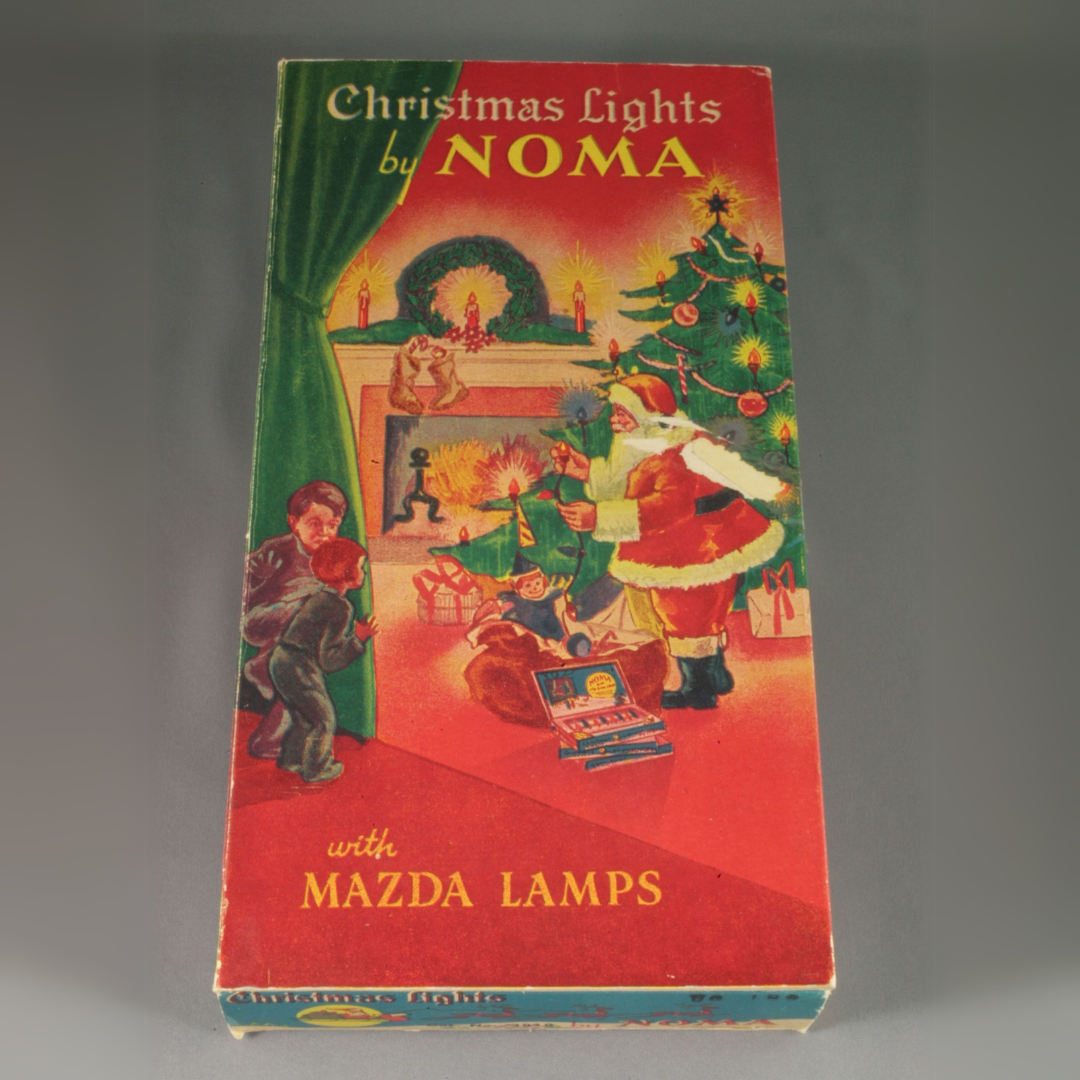

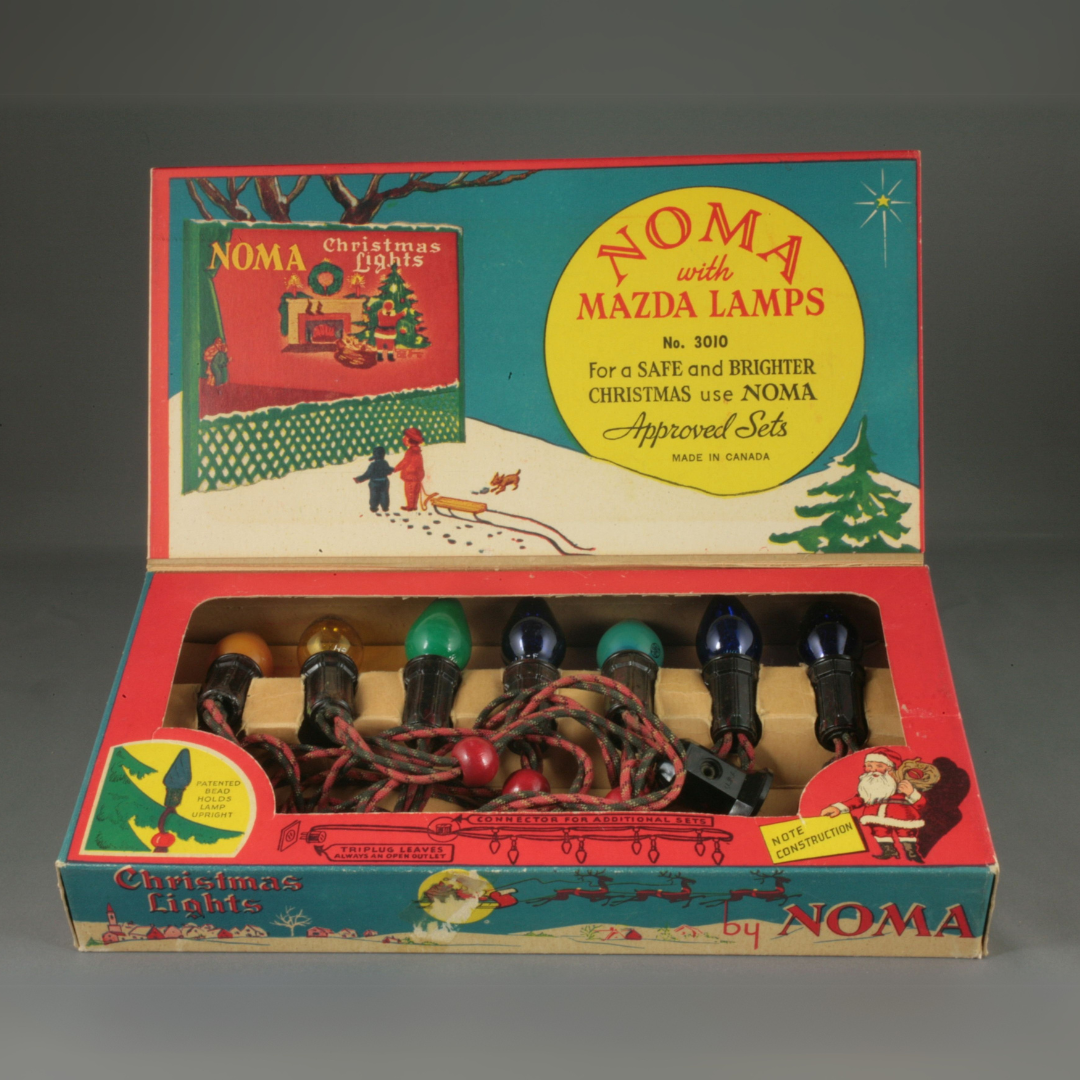

Each day started with a gallery walk through the whole museum. I would check for garbage and damage to exhibits, clean the glass cases and monitor humidity levels each morning. I was also given two large projects to undertake at the outset of my term. The first was to sort, organize and create a digital database for over three thousand research photos, which had been collected in cardboard boxes throughout the past decades. Despite their fascinating nature and relevance to the ongoing Bringing Our Stories Forward Capital Gallery Renewal Project, searching through these photos in their original state was impossible. Therefore, my goal was to make the collection easy to browse, as well as searchable for specific subjects via the digital database.

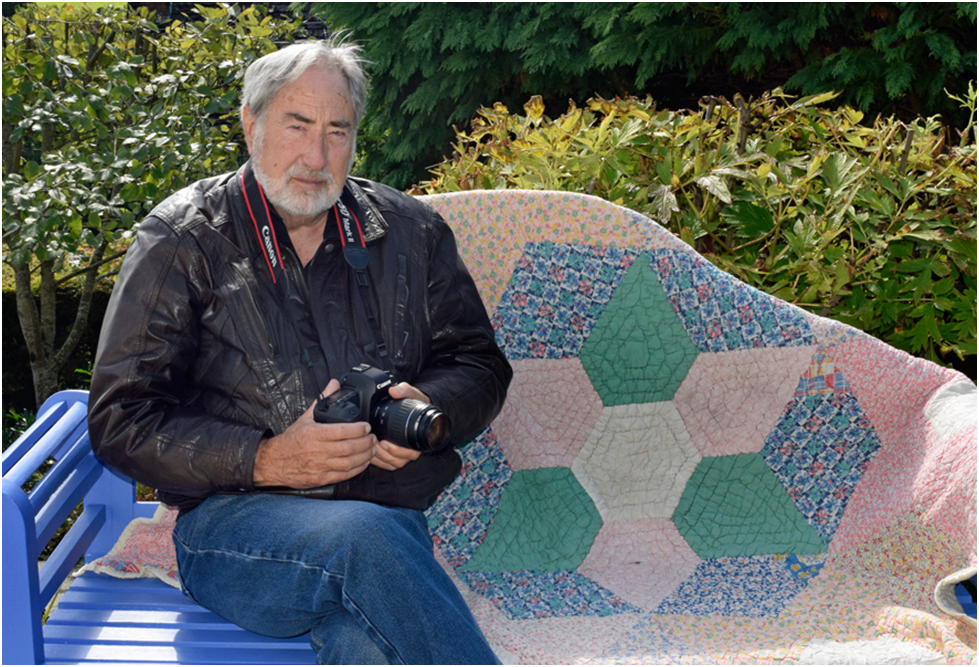

Image: Collections and Conservation Summer Student Matthew Gowdar.

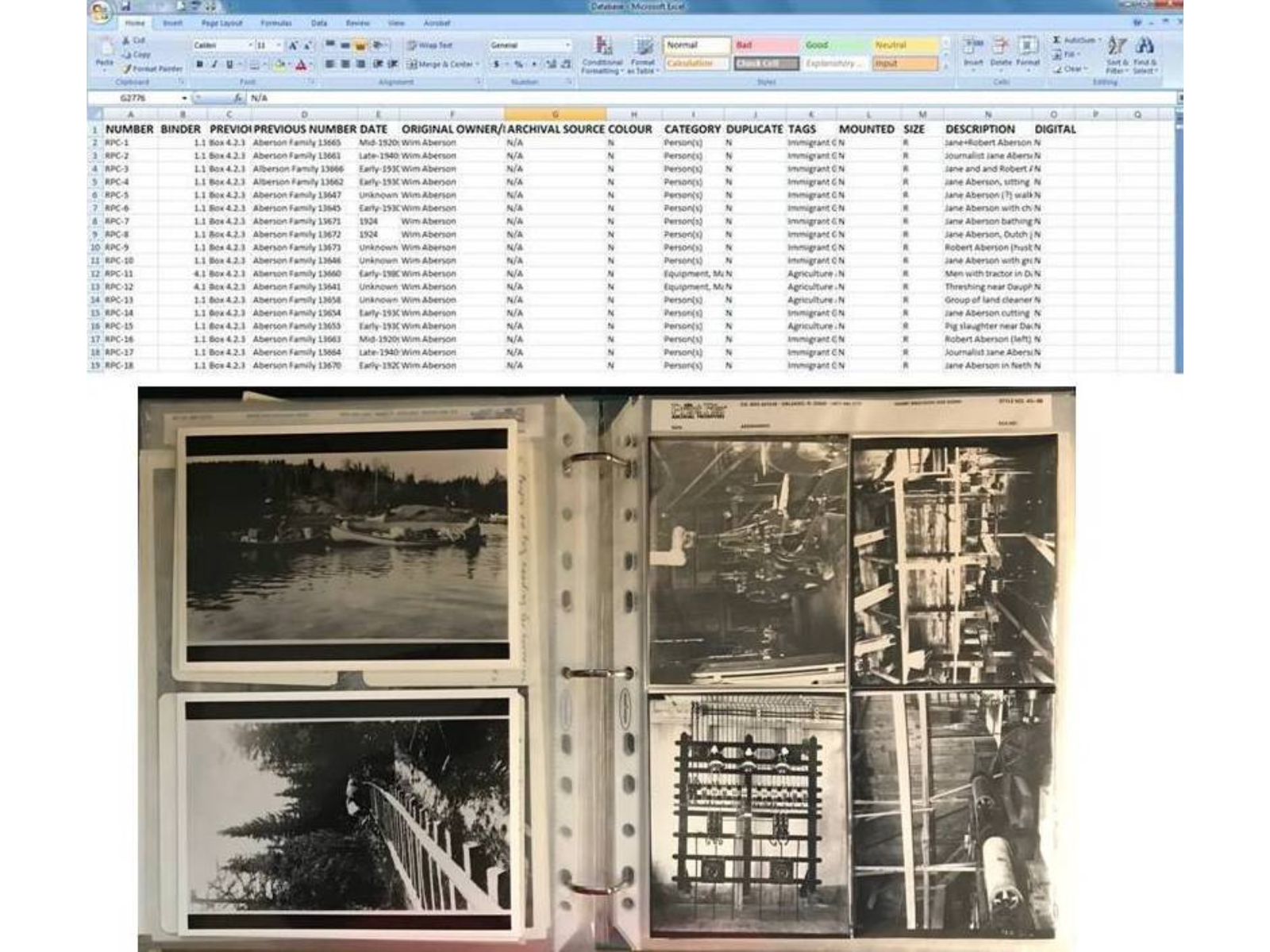

Using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, I created a series of binders, each assigned to a different subject. Each individual photograph corresponded to a different record in the database, which contained information such as date, photographer and a brief description. Although not quite complete, this system perfectly meets the project’s original goals.

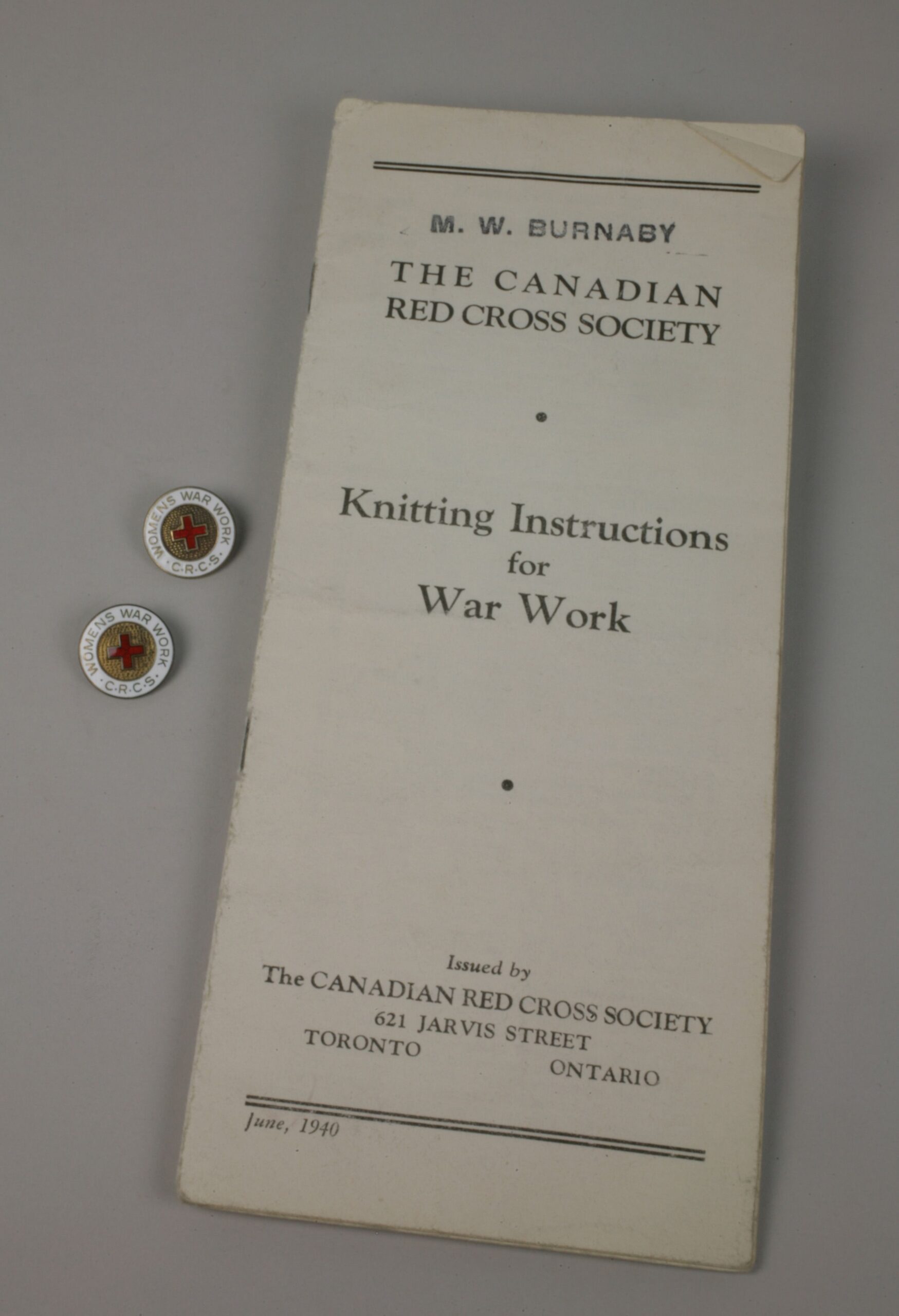

My second major task was a total revamp of the Manitoba Museum’s Institutional archives. These boxes of documents were stored on dangerously unstable shelving which did not use the space efficiently, and contained a wealth of irrelevant material. The first step was to clean out the room as much as possible, followed by the disposal of the old shelving. New shelving was ordered and assembled. Each box was culled for material which could be discarded, and then placed on the new shelving. While this sounds simple enough, when one has over two hundred boxes to evaluate it becomes more complicated. The project was a great success, and resulted in a substantial increase in free space within the archive room.

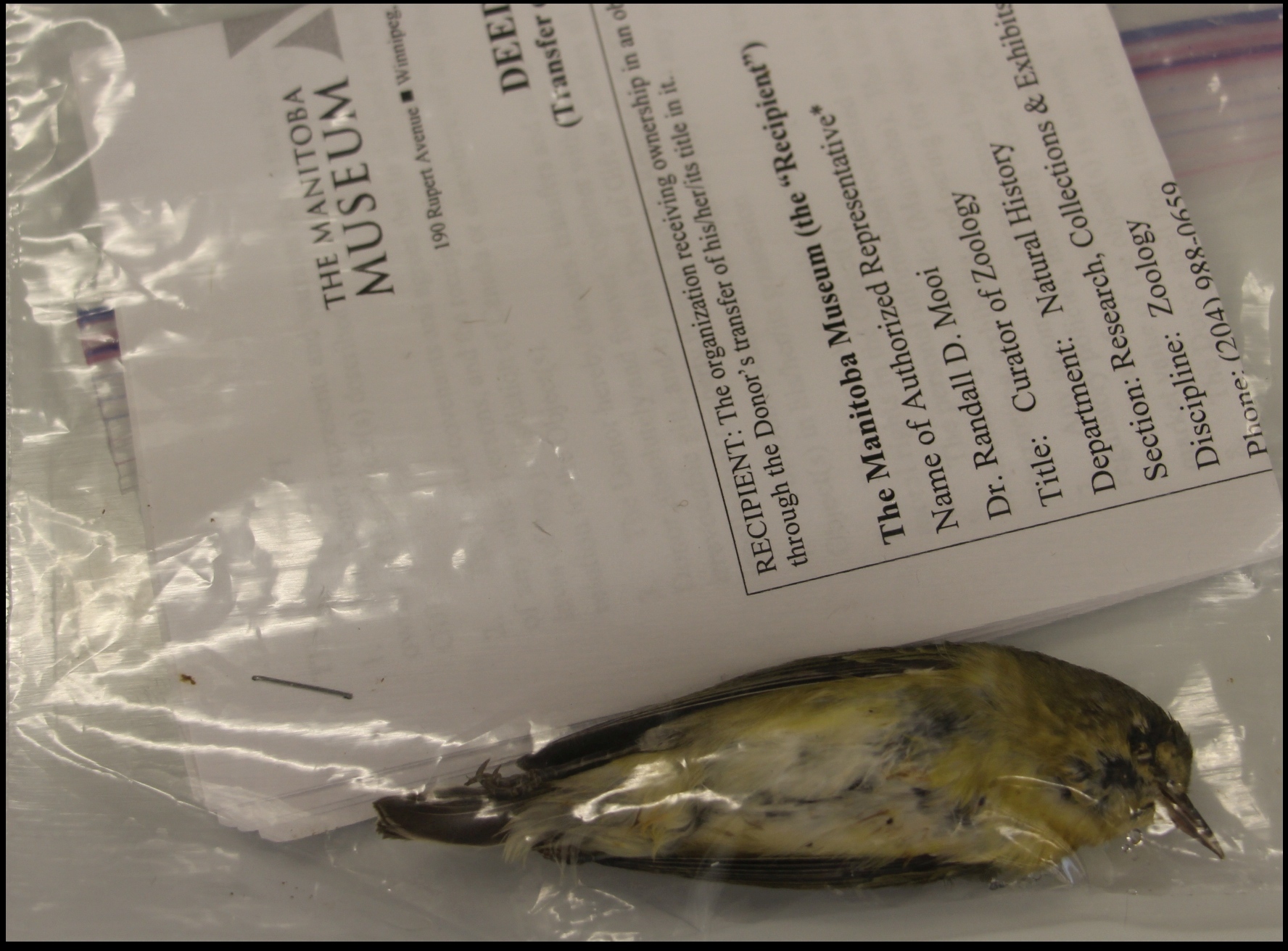

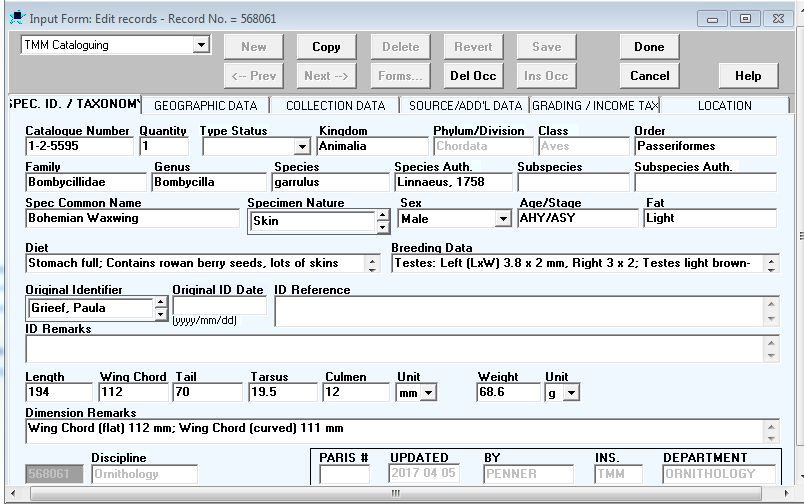

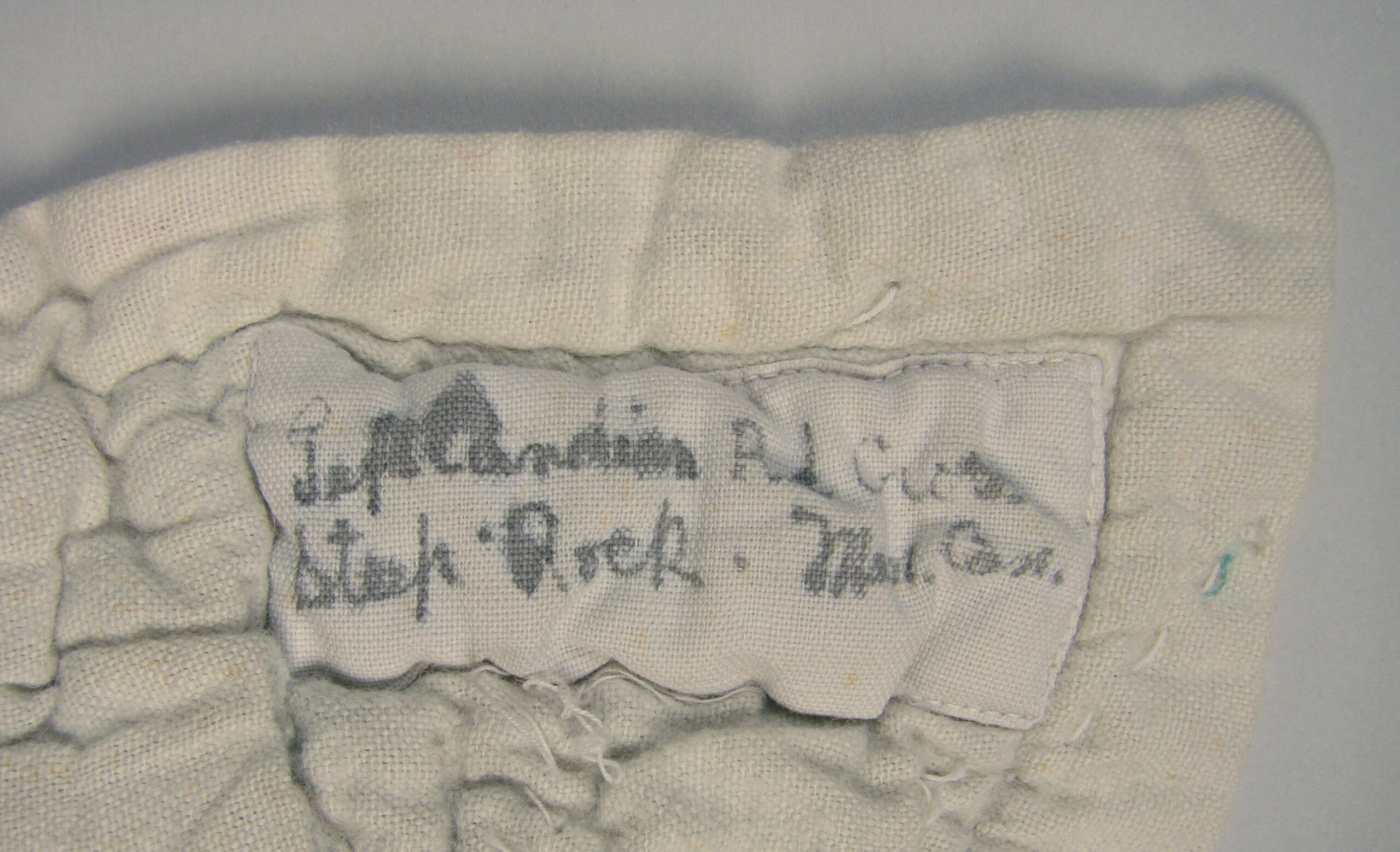

Image: Research photographs were put into a database and rehoused in archival sleeves. © Manitoba Museum

I was lucky enough to work alongside a group of intelligent and hardworking colleagues, whose passion for museum work was evident from day one. The support and direction I received from both Cindy Colford, Manager of Collections and Conservation, and Roland Sawatsky, Curator of History, was invaluable. I also would like to thank Loren Rudisuela, Carolyn Sirett, Nancy Anderson, Cortney Pachet, and Amelia Fay and numerous other staff members for all the help they provided me over the last few months. The Manitoba Museum truly employs a special group of people.