Posted on: Wednesday December 14, 2011

Part II

During the Battle of Hong Kong, 290 of the 1,975 Canadians defending the island were killed in battle. After the Canadians were captured by the Japanese on Christmas Day, 1941, Canadian soldiers were taken into a brutal period of captivity, first in Hong Kong and then in Japan. Deprived of food and sanitary conditions, 267 more Canadians died as Prisoners of War.

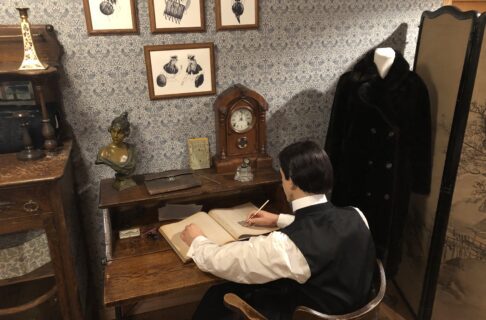

In Hong Kong the Winnipeg Grenadiers suffered through long days of hunger and boredom. Woodworking contests were set up to keep minds and hands busy. A very recent donation to the Manitoba Museum includes one of these wooden artifacts: a hand-carved chess set inlaid with bamboo. This belonged to Lieutenant Richard Maze, who signed up for the Saskatchewan regiment with Corrigan (see Part I here): they were both later moved to the Winnipeg Grenadiers. The complete set features tiny chess pieces (about 2 cm tall) that include thin pegs to secure them to the board. Lieutenant Maze received the set from a fellow prisoner who constructed it from wood scraps found around the Kawloon POW Camp, Hong Kong. This little chess set is an example of how creative activity and friendship helped the prisoners withstand deprivation in such difficult conditions. Thanks to Rose-Ann Lewis and Ann Maze for the donation of Lieutenant Maze’s Hong Kong Veterans items to the Manitoba Museum.

Image: Chess set made by Winnipeg Grenadier POW, Hong Kong, ca. 1942-1944. H9-37-547-a-ag. Unless otherwise noted, The Manitoba Museum holds copyright to the material on this site.

The Canadians were later moved to a POW camp in Japan, where many worked in mines and they were limited to less than 800 calories of food a day.

The Japanese government recently offered a full apology for the treatment of Canadians in these POW camps. (Read a CBC article covering the apology, here).

Reactions among Canadians are mixed, with some accepting the apology while others say it’s too little, too late. What do you think?