Posted on: Monday December 31, 2012

By Dr. Graham Young, past Curator of Palaeontology & Geology

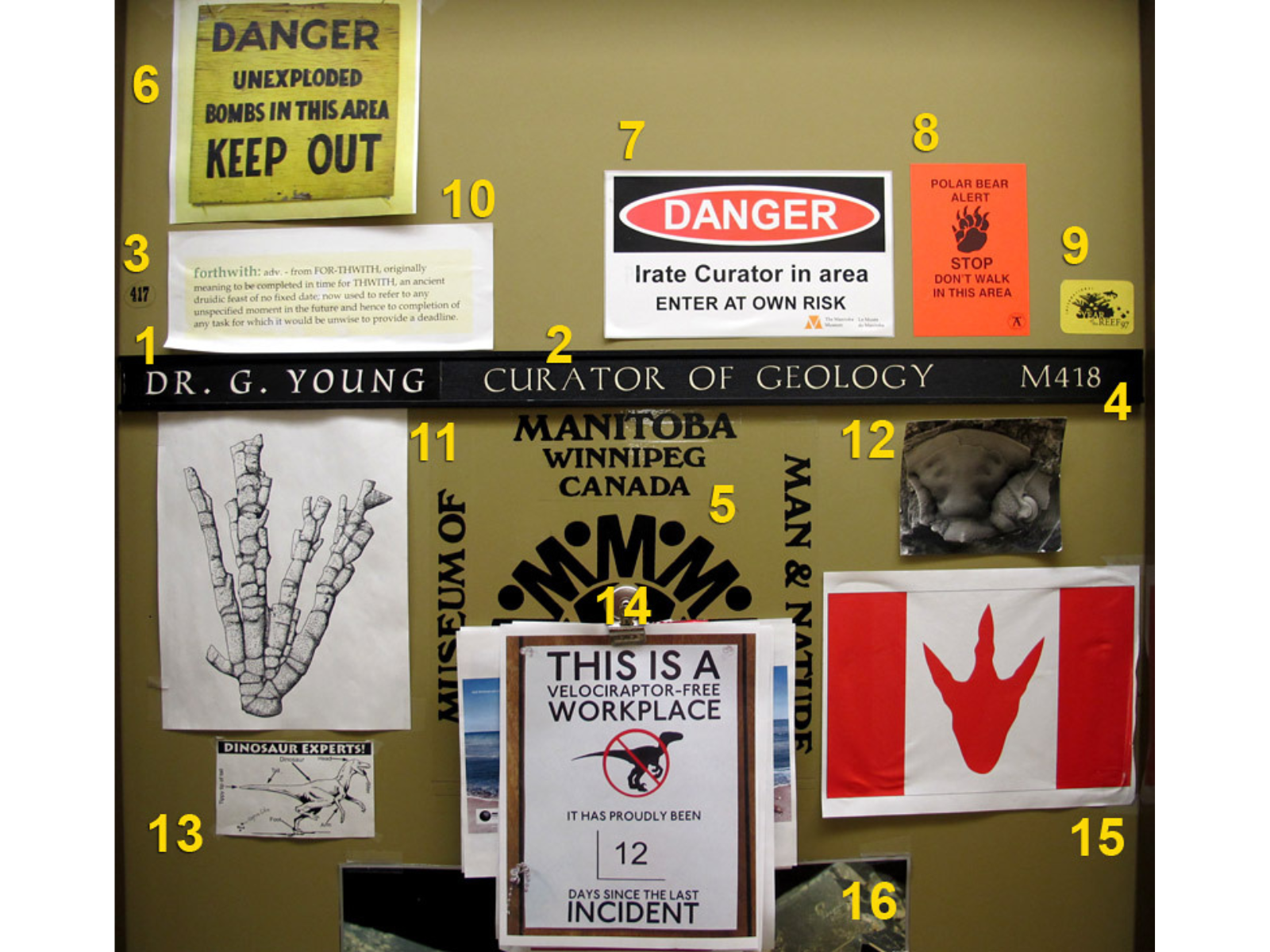

When I started this blog a couple of years ago, one of my main intentions was to share the various items and phenomena that are within close reach of my desk, here on the 4th floor of the Museum tower. With that in mind, and since at lunchtime on New Year’s Eve we have reached a point in the year where serious and scholarly content should not be expected, I have decided to provide you with an annotated view of my office door.

In general, this curator’s door is far from curated, in the sense of having organized content. Rather, it is an odd mixture of items that I have randomly decided to exhibit, pieces that other people decided should be placed on my door, and things that seem to have flown in and stuck there all by themselves. With that in mind, the following is an annotated pictorial guide to items that can be seen on my door right now.

1, 2. When I started work at the Museum almost 20 years ago, the “Curator of Geology” plate was already on the door. As I was a part-time term employee for the first few years, I didn’t think that I should waste the Museum’s funds by requesting a personal nameplate. After a year or so, however, we made a “temporary” plate by laminating a laser-printed output to cardstock. I am, of course, still using the temporary plate, as it works just fine and I still like to avoid wasting money!

3, 4. For some unknown reason, the door suggests that my office is both Room 417 and Room 418. The 417 is, however, struck through with pen, indicating that 418 may be the accurate number.

5. When I started here, the Museum was called the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature, and the name and logo had been very nicely laminated to my door. I really like our new name, but I also like being surrounded by reminders of history.

6-8. My door seems to have acquired a variety of warning signs, perhaps in the hope that potential visitors will leave me to peacefully contemplate the riddles of the universe (note: these haven’t worked so far!). Actually, numbers 6 and 8 are copies of signs seen near Churchill, and are reminders of northern fieldwork. Number 7 is a joke sign produced by former Curator of Zoology Gavin Hanke, when he was making a “bear warning” sign for the Parklands/Mixed Woods Gallery. Some thoughtful person has, with a pencil, modified “Irate Curator” to “Pirate Curator”, which brings to mind all sorts of interesting images. Arrr.

9. This sticker promotes the “International Year of the Reef 1997”. Sadly, evidence would suggest that this was one of the less successful International Years.

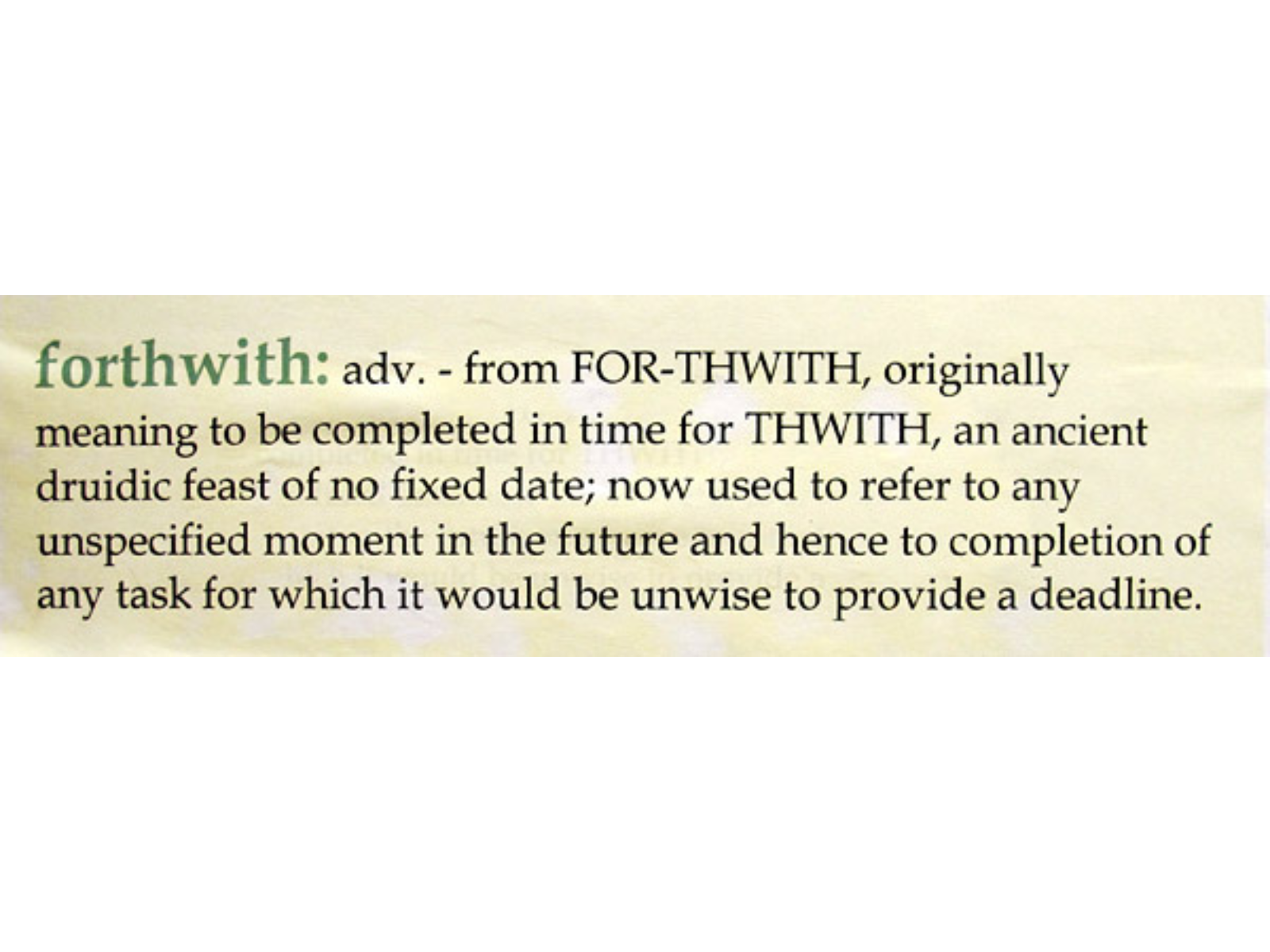

10. The definition of forthwith came from the brain of my friend Dave Rudkin. With this in mind, I am always happy to state that I will produce a document “forthwith.”

11. This lovely pen-and-ink sketch of the Ordovician branching coral Pragnellia arborescens is by Museum artist and preparator Debbie Thompson. It depicts the holotype of this species, specimen I-206.

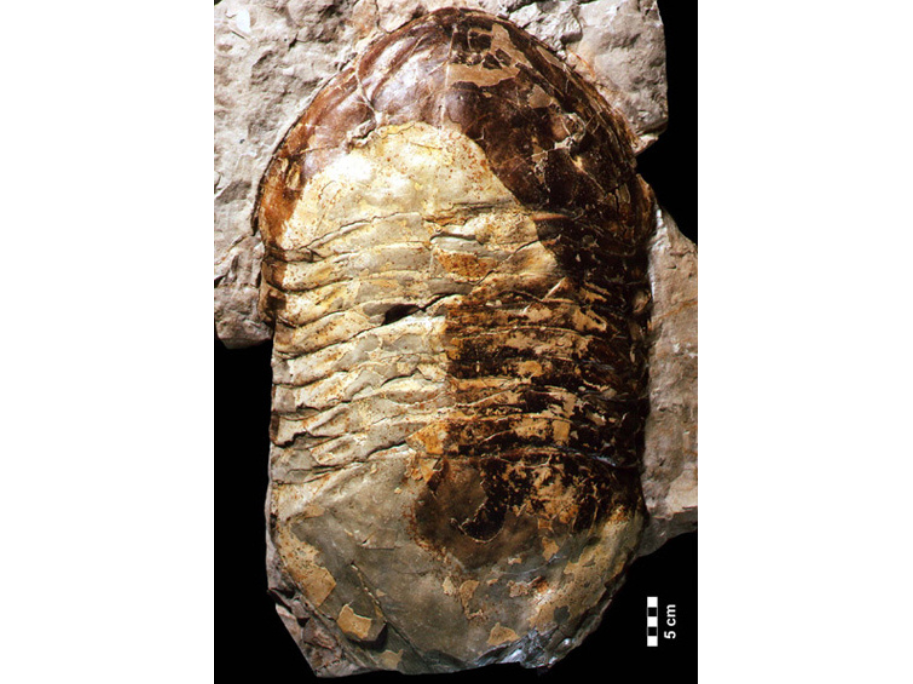

12. A photo of the head (cranidium) of a Silurian trilobite from the Gaspé Peninsula of Québec is there to remind me of two things. First, it is an image I took 30 years ago using what is now ancient technology (a large-format film camera), and its tone and beauty demonstrate that new methods are not always the best methods. Second, since it is from a research project that I never completed, it is a reminder not to keep taking on new projects that I will not be able to finish!

13. The obligatory dinosaur cartoon.

14. This is a Velociraptor-free workplace, and there have been no incidents since this sign was put up almost a month ago.

15. I produced this version of the Canadian flag for my other blog a couple of years ago, after reading Michael Flanders’ pronouncement from the 1960s that our flag looked like a dinosaur footprint.

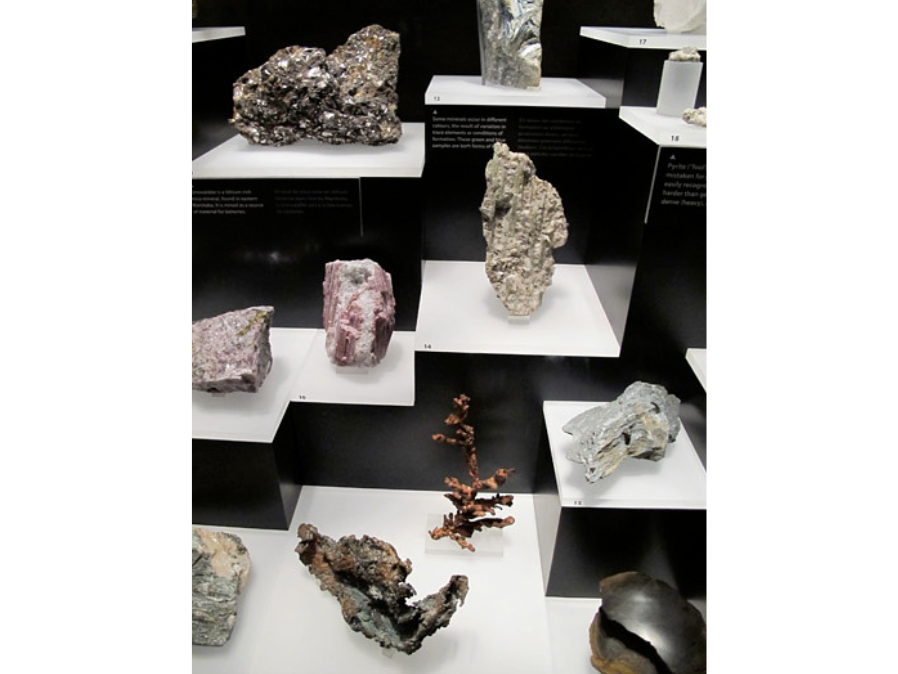

16. This was a nice poster of a pyrite crystal, but it is sadly becoming greenish and tattered, and I really should replace it!