By Dr. Graham Young, past Curator of Palaeontology & Geology

Bison rubbing stones are icons of the prairies. These large stones were originally transported south by Ice Age glaciers, then left behind on the prairies when the glaciers melted and receded roughly 12,000 years ago. They are therefore considered to be a form of fieldstone, and such large blocks of fieldstone are commonly called glacial erratics.

In the millennia since the glaciers left this region, rubbing stones have undergone a lengthy and intensive polishing process. These are boulders that were tall enough that they were made use of by itchy bison, who needed to shed their heavy winter coats or scratch after being bitten by flies and mosquitoes. The rubbing by bison over such a long time interval, along with the oils from the animals’ hides, gives rubbing stones a distinctive patina, and a rubbing stone is typically surrounded by a ring of flattened, eroded earth.

The bison rubbing stone is beside the Pronghorn Diorama, at the entrance to the Prairies Gallery.

A rubbing stone at the Star Mound historic site.

For our new Prairies Gallery, we knew that we wanted to include this sort of defining prairie element as a full-sized touchable piece, but we also knew that a cast or sculpted stone just wouldn’t do it. We had to acquire a real stone, and it had to be light enough that it could be moved into our gallery and placed safely on the gallery floor for an indefinite period of time. Since the gallery’s weight allowance is quite limited, how could this possibly be done?

As was the case for our fieldstone wall, we discussed this with stonemason Todd Braun quite early in the gallery development process. Although we thought that there should be a real boulder in the gallery, we also knew that it could not be a recognized rubbing stone, as those are heritage objects that should be left undisturbed in their original locations. Instead, Todd suggested that he could acquire a boulder of suitable size and rock type from gravel pits in the Morden area, and that he would prepare the boulder so that it could meet the floor loading limits and other requirements for placement in our gallery.

Kevin Brownlee, Curator of Archaeology, examined the stone when we first saw it outside Todd Braun’s workshop in February, 2020.

The stone is a boulder of migmatite, a rock type that exhibits coloured bands made up of different minerals.

Todd located the stone in late 2019, and we first saw it during a visit to his workshop in February, 2020. It is a very substantial boulder of migmatite, a high-grade metamorphic rock with aligned layers of minerals, which was formed under great heat and pressure deep in the Earth. Todd explained how he planned to cut off one end of the boulder so that it would be lighter and so that it would be stable standing on the floor. He would then use cutting and grinding power tools to hollow out the stone, starting from that flat end. It would therefore still look like a large solid boulder, but it would actually be more like a thick-shelled egg, with much of its internal mass replaced by air.

Once we had a plan in place, the boulder had to wait until Todd had the time to prepare it. He was busy completing the fieldstone wall for our gallery, and was not able to turn his attention to the boulder until the fall of 2020. The cutting and hollowing of the stone turned out to be very labour intensive; the rock was very hard, and Todd was also afraid that fractures might develop if he tried to remove too much rock at once, or pushed too hard on it. It would have been a disaster to have the boulder go to pieces at this stage!

Todd Braun used power tools to hollow out the boulder (this is a still from a video by Todd).

Todd told us that we were getting our money’s worth, since the job was more work than he had anticipated, but the hollowing out was completed by late November. He was also able to put a bit of a polish on the outer surface of the stone, to mimic the effect of rubbing by thousands of bison.

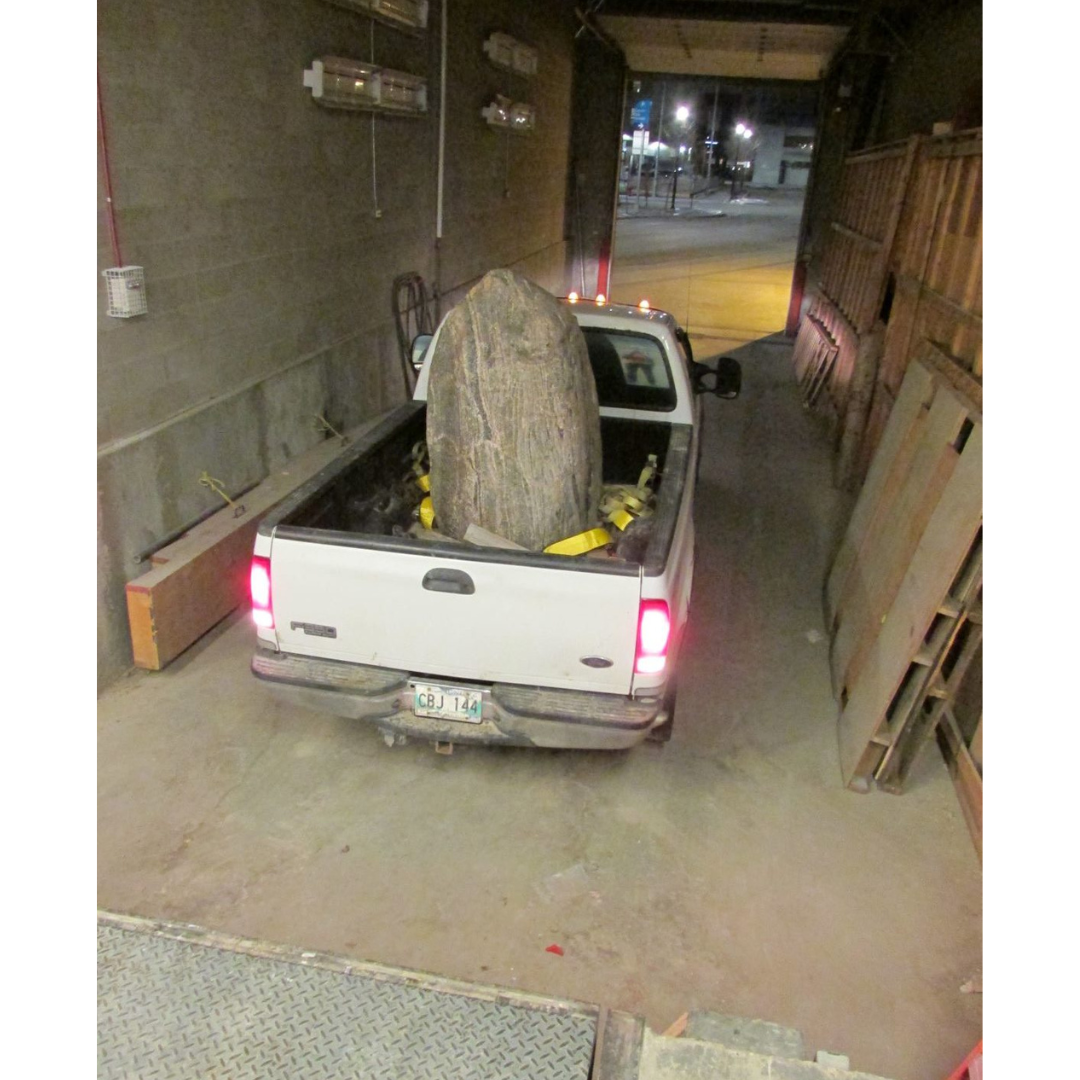

Todd used his tractor to lift the boulder into the back of his truck. Very early one morning, he drove to Winnipeg before there was significant traffic on the roads. The truck was backed into our loading dock, the hoist was attached to the heavy-duty straps that Todd had placed beneath the boulder, and the stone was lifted very smoothly onto a pallet jack. We were grateful at this stage that the boulder had lost so much of its original weight!

The boulder was hollowed out and ready to travel to Winnipeg (photo by Todd Braun).

The boulder was lifted into Todd’s truck . . . (photo by Todd Braun).

. . . and arrived at our loading dock very early in the morning (photo by Randy Mooi).

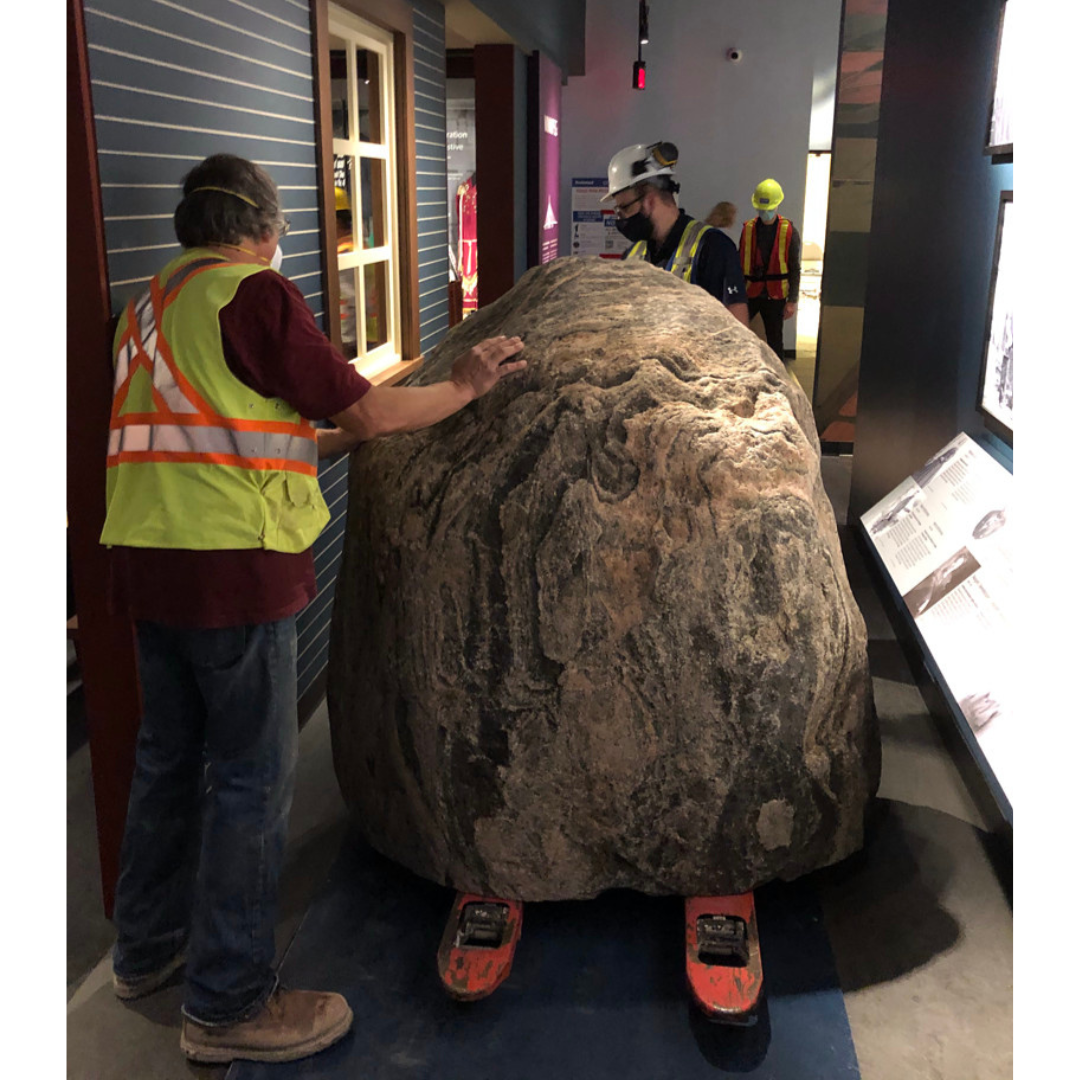

We had a crew of four on hand to assist Todd with moving the boulder into the gallery: an expert construction manager, and three curators to provide the grunt labour. Since we had measured all the doorways and halls in advance of this move, we knew that there would be a few tricky spots during the stone’s travel through the building, but that it should just fit through all of those.

The loading dock hoist was used to lift the boulder from the back of the truck (photo by Randy Mooi)…

… and to position it on the platform, where the pallet jack could be lined up underneath (photo by Randy Mooi).

First, we trundled it down a long corridor and through the Museum’s workshops, then out into the Welcome Gallery. Since there was new flooring in the galleries, we had to begin laying down sheets of board when we left the workshop space. There were several large plywood sheets, so it was a matter of laying down a row of boards along the planned path, then lifting each board after we passed over it, and moving it to the front of the other boards so that there would always be a safe surface for the pallet jack.

The stone turned out to have a bit of a “mind of its own” when it came to the direction our route would take, and there was some manoeuvring required to get it lined up with the doorway that would take us into the Winnipeg Gallery area. This gallery was another tight spot, and after some discussion and changing of direction, the boulder slipped through. We then had a clear run to its final location by the Pronghorn Diorama.

The boulder began its journey down the corridor toward the workshops (photo by Randy Mooi).

In the Welcome Gallery, the stone came as close to bison as it would ever be in its time at the Museum! Note the sheets of plywood protecting the gallery floor (photo by Randy Mooi).

In the Winnipeg Gallery, there was discussion of how we could get the boulder past some exhibits.

The pallet jack was rolled to the location that had been selected for the boulder’s final position, and the stone was gently (VERY gently!) shifted onto some large wedges that Todd had brought along for the task. By levering with heavy pry bars, the wedges could be gradually removed and the boulder settled into place.

The next time you are in our new Prairies Gallery, I hope you will take a good look at the rubbing stone and other exhibits. Many Museum exhibits may look like simple things, but the stories behind them are often quite complicated!

The last wedges were removed as the boulder was lowered into place (photo by Randy Mooi).