Posted on: Friday March 15, 2013

By Dr. Graham Young, past Curator of Palaeontology & Geology

Looking through my window at the still-snowy, still-wintry Winnipeg streetscape, I have to remind myself that spring is not far away. Soon the snow will leave and we will again be able to begin one of the most pleasurable of the Museum’s activities: fieldwork. Last year, between various other projects, I worked with Bob Elias (University of Manitoba) and Ed Dobrzanski on gathering information that we could use in a field guidebook for this spring’s Winnipeg GAC-MAC meeting (Geological Association of Canada – Mineralogical Association of Canada).

Most of the sites we planned to include in the guidebook were well known to us, but there was one glaring absence: Bob and I had never seen the type section for the Lower Silurian Fisher Branch Formation, and Ed had visited it just once almost 50 years ago! From the published scientific work we knew where the site should be: all we had to do was to visit and document it. This seemed like a straightforward mission, as we already had maps and a geographic position, but as it turned out we made three trips to the Fisher Branch area before the work was complete.

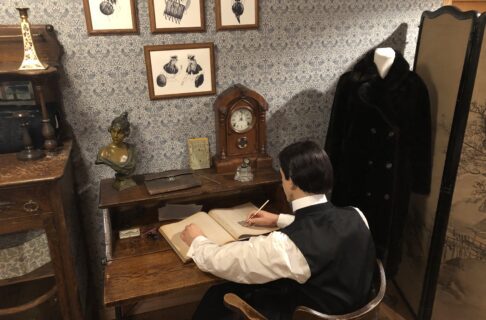

Image: Tramping through the woods in October.

The first trip, in late May, was after several days of rain. We found the right roads, we located the property on which the site should be located, and we met and received help from the very kind owners of the property. But the roads were continuous mud in places, and we were told that the field track to the site would be impassable that day. We would need to come back later when the weather had been dry for a while.

On the first day out, Ed gathers GPS data from a little patch of bedrock outcrop some distance from the actual locality, while it appears that Bob is not really enjoying the misty weather.

No, the collie did not chase us into the car. It was extremely friendly, and just wanted us to hang around longer!

Bob demonstrates “cow-whispering” skills of which Ed and I had been previously unaware. Bob says later that they were more attentive than his human classes often are, though their attention did not seem to last very long.

This is what the car looked like after we had finished many miles on muddy roads. Ed and Bob are inside, but you can’t really see them through the nearly-opaque windows. That’s the Lundar Goose in the background.

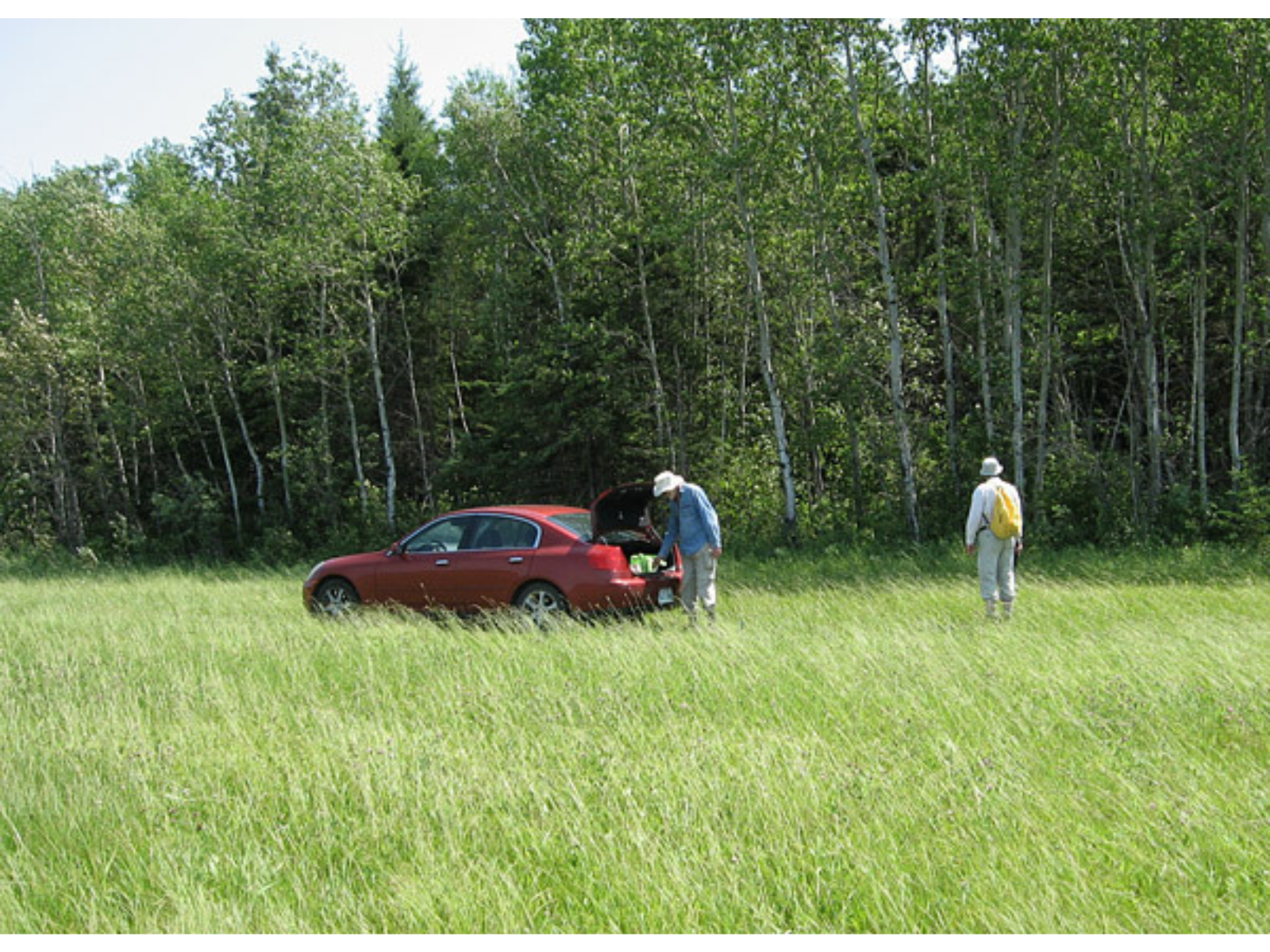

The second day was one of those hot, dry, breezy July days. The air motion was sufficient to cool us and to keep mosquitoes and flies from being too much of a nuisance. We drove through fields almost to the site, without even getting dirt on the car! Tucking trousers into socks to keep the nasty wood ticks from climbing our legs (this may look goofy, but it works), we pushed through the dense brush. We rapidly discovered four nice scarp sections in the trees. The farthest of these looked promising because it showed the best exposure of the Stonewall Formation, which lies under the Fisher Branch. This site, however, turned out to be already occupied: a bear grunted and huffed from the underlying crevice when we got too close!

We quickly decided to measure the next section along instead. Data and rock samples were easily gathered, but we could not get decent photos of the rocks because the view was blocked by foliage whichever way we turned. We would need to return in the autumn, after the trees had lost their leaves.

In the perfect July weather, Bob (right) and I unload gear at the edge of the field. (photo by Ed Dobrzanski)

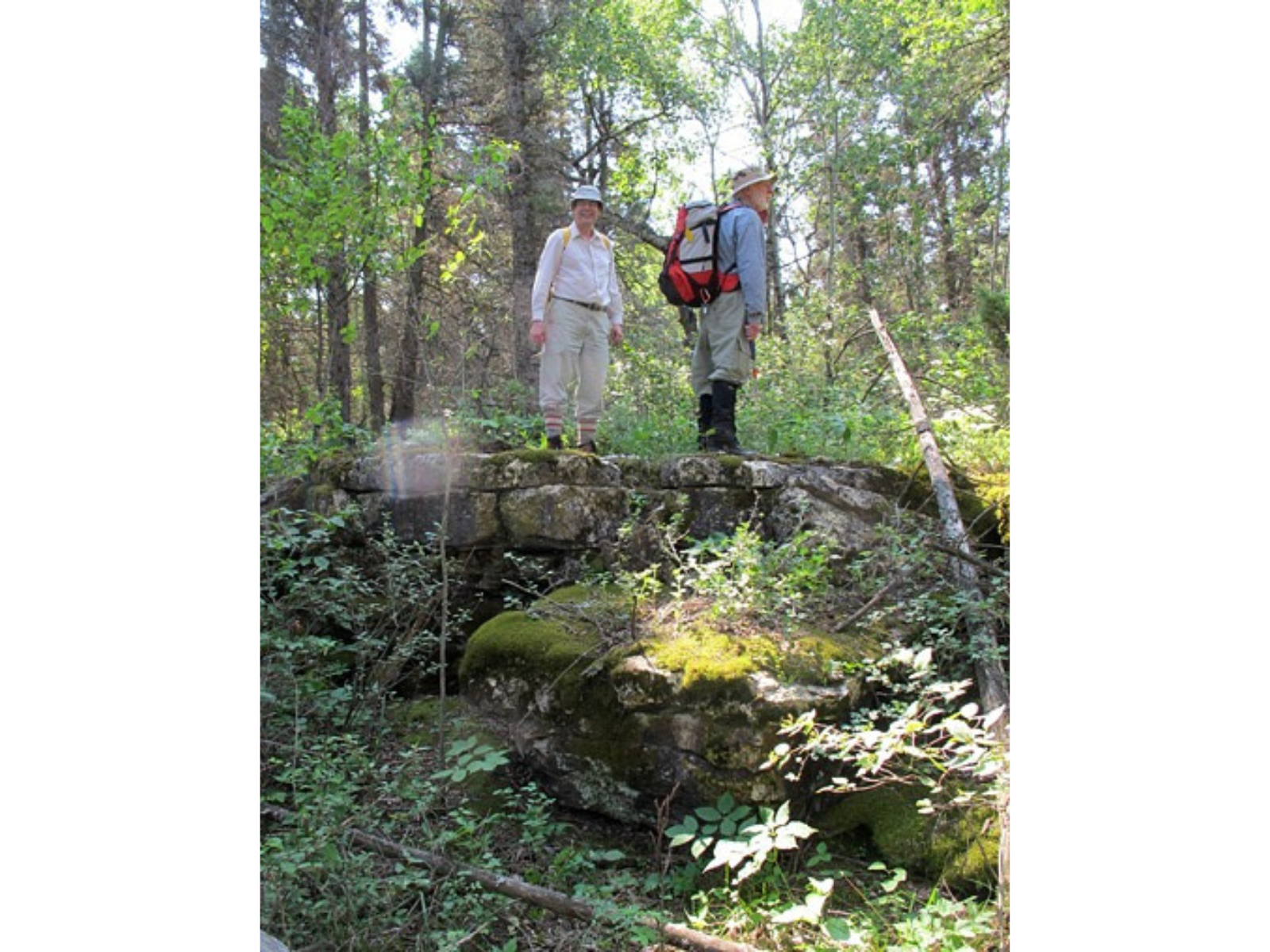

Success! Bob and Ed on top of a bedrock scarp.

A wood tick that, thanks to the “pants tucked into socks” approach, was discovered on the outside of my clothing.

By mid October the leaves were all gone and the weather was still lovely; ideal for our final “day out” near Fisher Branch. We stopped at Stony Mountain and Stonewall to check out conditions at those localities, then drove north to Fisher Branch by lunchtime. In the field beside the sites we were met by a large herd of cows (perhaps the Interlake should be advertised as “Land of Cows”?), some of which became very interested in our Jeep. The bear was apparently no longer in residence at the farthest scarp, so we were free to examine the rock, take photographs, and gather a set of isotope samples. Later in the afternoon, we tramped up over the hill above the scarp, just to make sure that there was no further unexamined outcrop.

It was a perfect autumn day; the last perfect field day of the year, as it turned out. Our drive to Grand Rapids under rather less pleasant conditions was to follow just a couple of days later.

It is good that Jeeps are designed to take a licking.

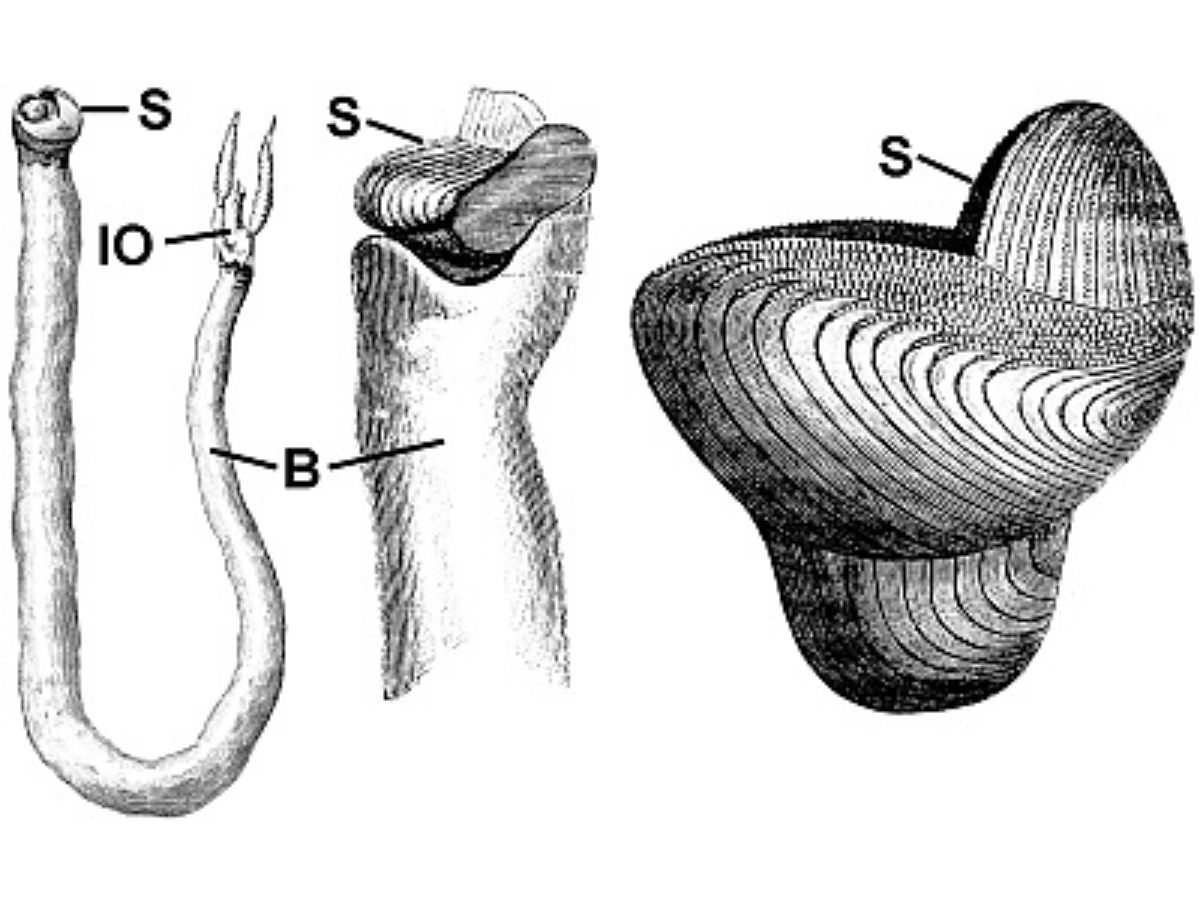

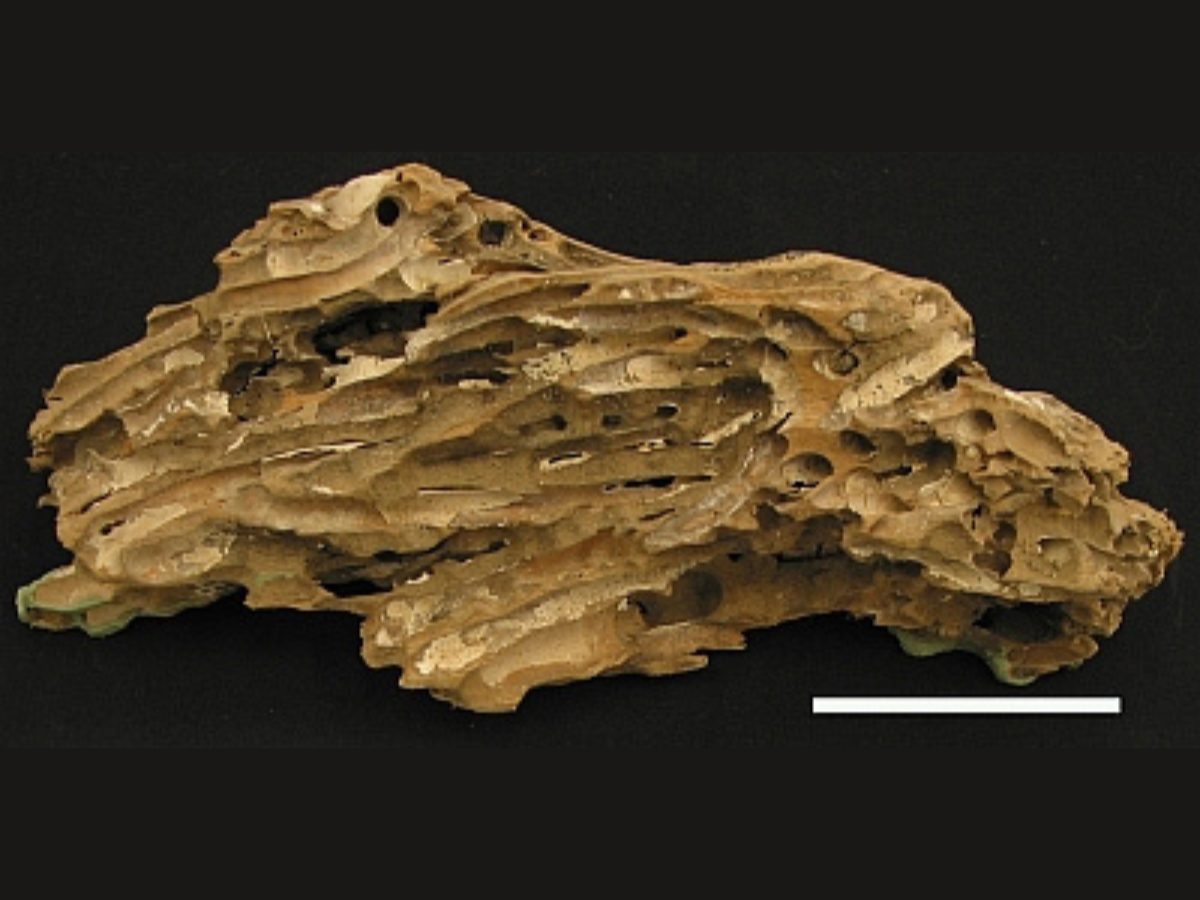

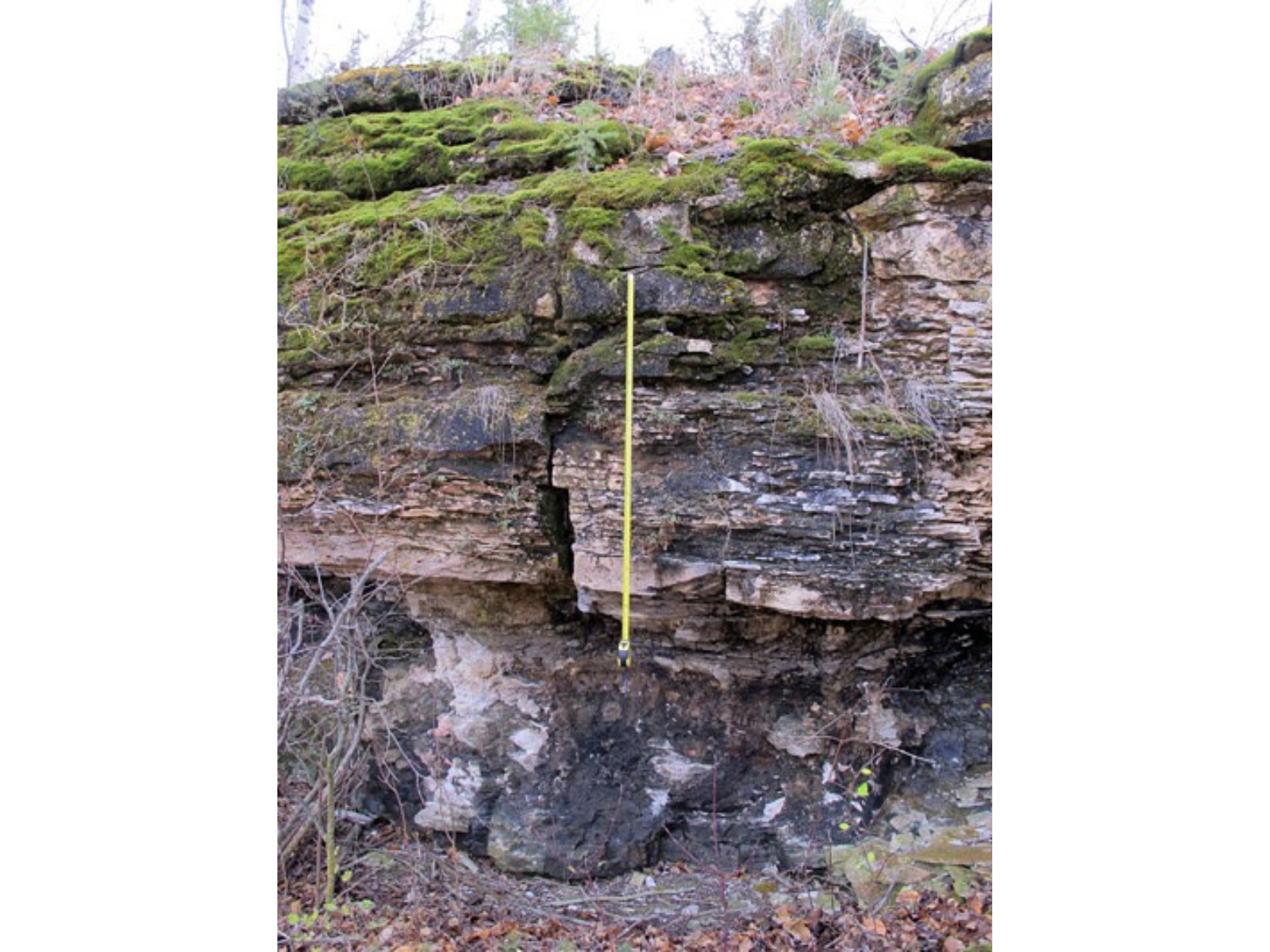

The body of the tape measure rests at the boundary between the Stonewall Formation (below) and Fisher Branch Formation (above). That boundary is now considered to also represent the Ordovician-Silurian Boundary, so this site is very significant as the only place this systemic boundary can be observed in southern Manitoba. Length of the tape measure is 1 metre.

The farm includes several wonderful buildings from the original Ukrainian settlement of this area, about a century ago.