During the current pandemic, we have all become used to the idea of virtual connections and well aware of opportunities to serve communities at home and even around the world. This is nothing new for scientific research at the Manitoba Museum – it has been reaching global audiences since we opened in 1970.

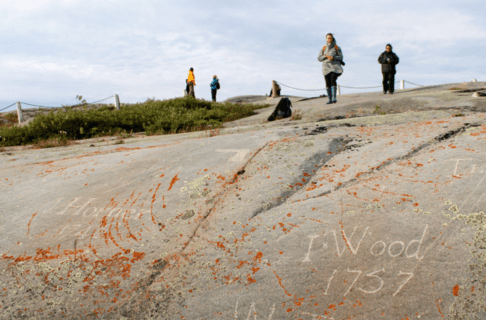

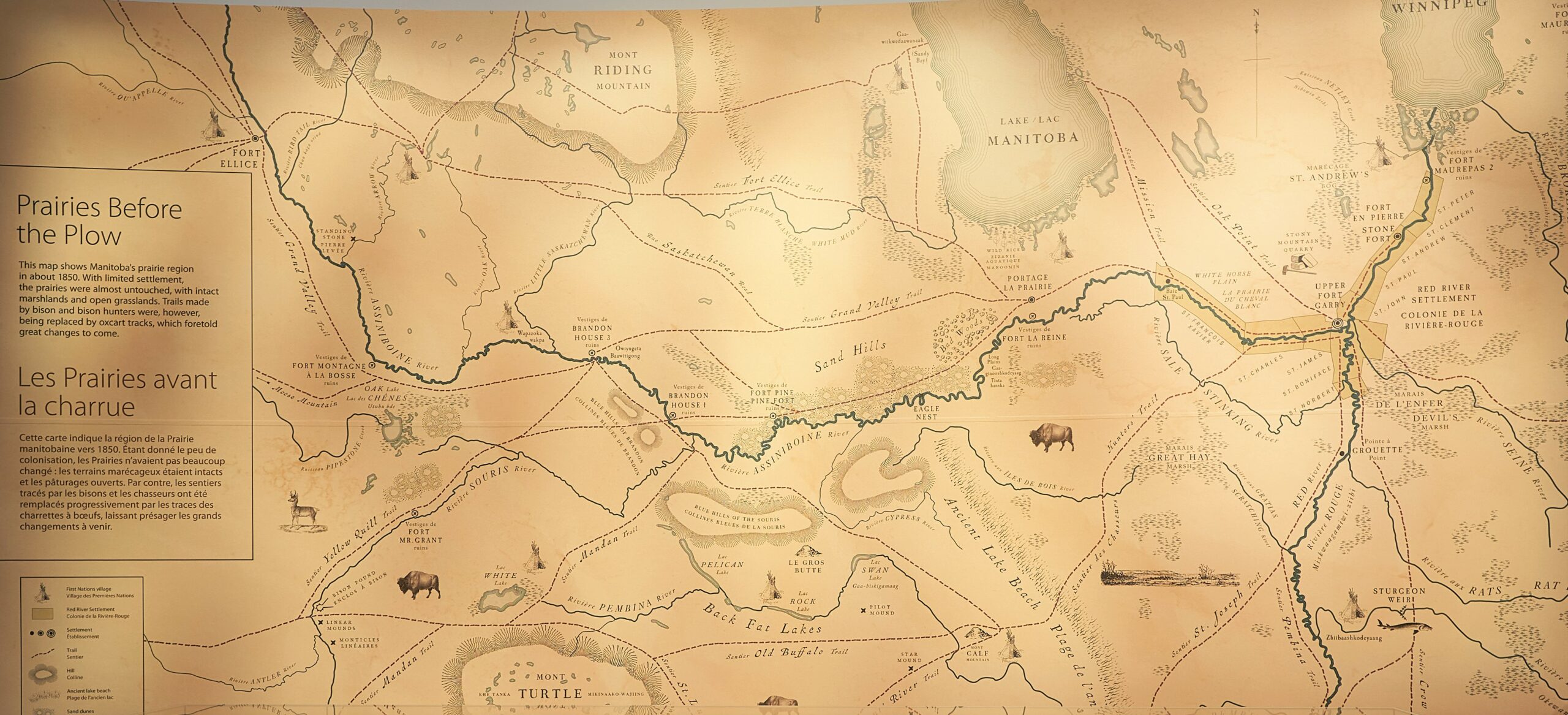

Image below: Museum exhibitions, like the new Prairies Gallery, are the result of scientific research and collaborations which provide both the specimens and their interpretation that visitors see when they visit. © Manitoba Museum/Ian McCausland

The Global Reach of Museum Science

The natural world isn’t bound by provincial and national borders, so scientific discoveries at the Manitoba Museum, made available in international publications, inform scientists, conservationists, and policy-makers here in Manitoba and abroad. Expertise in the Natural History section extends to animals and plants, both living and fossil, that occur around the world.

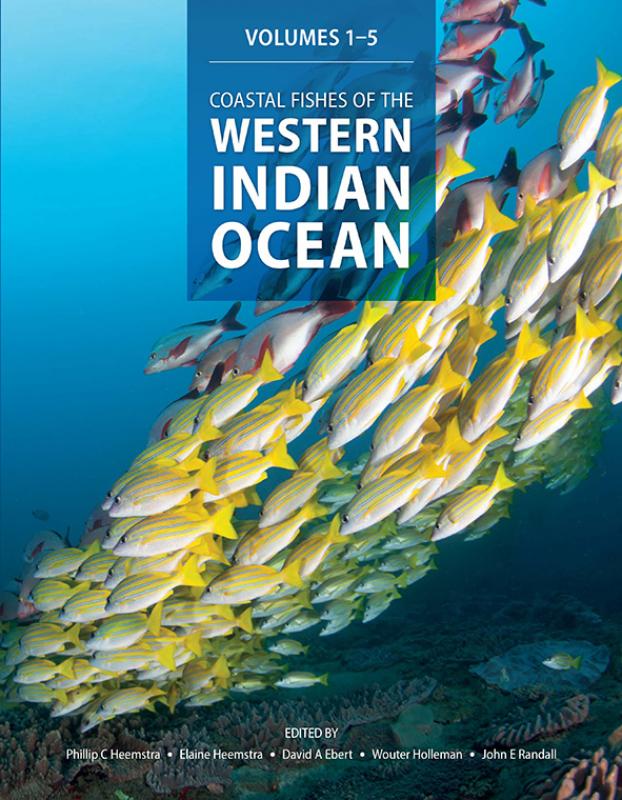

Fishes on the other side of the World

The Museum has recently collaborated on a comprehensive guide to the coastal fishes of the western Indian Ocean, an area including the Red Sea, east coast of Africa, and Madagascar to the southern tip of India. This project, spear-headed by the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity, involved over 100 contributors from 20 countries, including the Manitoba Museum.

The five volumes include descriptions of 3500 species of fishes and their distributions over the largest area of ocean ever to be covered by a publication of this kind. Because it is available online for free, it is a valuable resource for local fishermen, educators, conservationists, and governments – regardless of economic status – providing baseline data to understand and conserve ecosystems and manage fisheries resources.

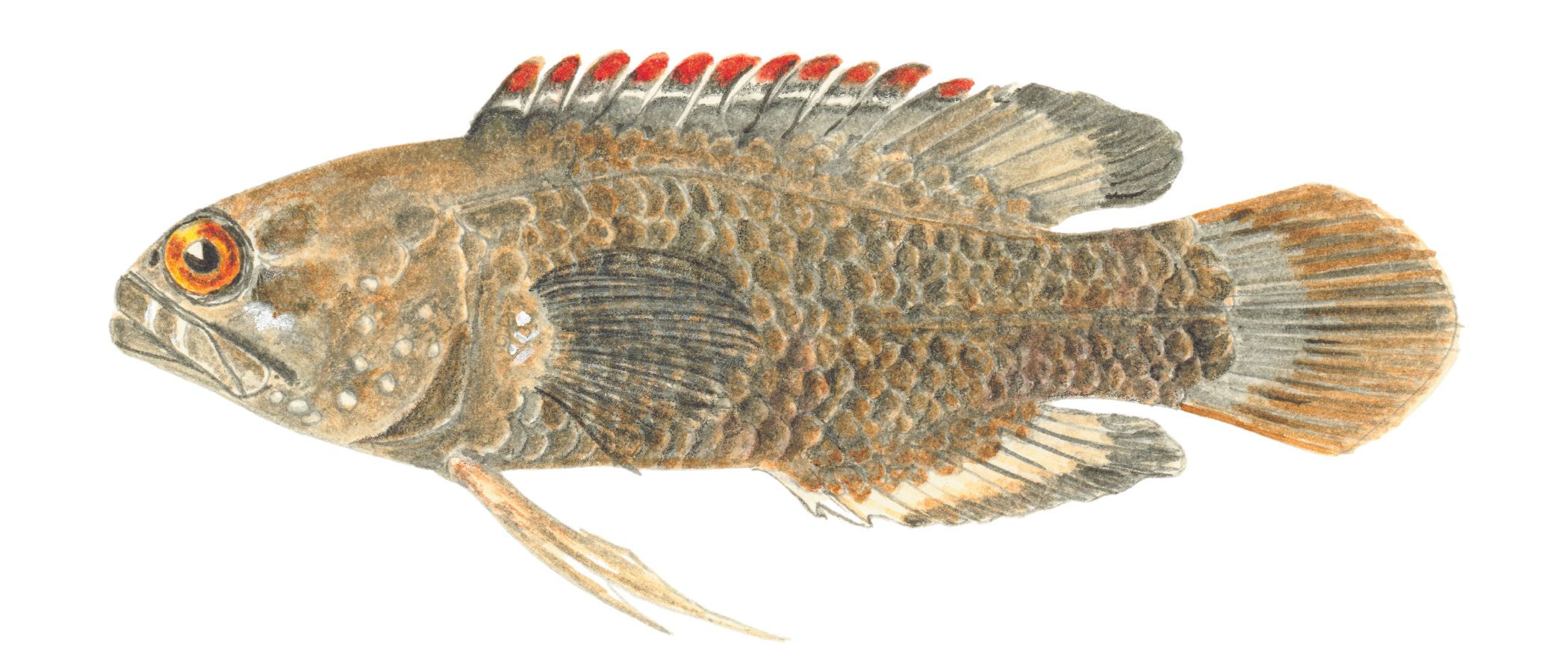

Image above: Known from only four specimens in museum collections, Winterbottom’s goby (Callogobius winterbottomi Delventhal & Mooi) was first recognized during detailed study at the Manitoba Museum. ©Manitoba Museum

Museum Science – Collaboration and Community Impact

These kinds of partnerships are a direct result of the expertise that the Manitoba Museum brings to the scientific community through original research. In turn, these scientific contributions shape how society understands and responsibly engages with the environment. The work of Manitoba Museum scientists and their national and international collaborators not only helps to understand and conserve the natural ecosystems at home, but makes an impact around the world.

Most Manitoba Museum scientific research is focused on Manitoba, including spring frog surveys by Curator of Zoology Randy Mooi that examine possible distribution changes due to climate change. Many discoveries, though, have applications well beyond our provincial borders. (Pictured. © P. Taylor)