Dearest Manitoba Museum friends,

First, thank you for being here. I appreciate how much information we receive on any given day, and how overwhelming it can feel. We often ask ourselves, ‘Is this message relevant to me or do I just delete it or move on?’ Fair question, and a necessary one if we want to create a life most meaningful to each of us. This message, aka my introductory blog, is one such piece of communication I hope you don’t automatically move on. I’m going to try my best to make reading this message worthy of your time and attention.

To begin, for those of you I haven’t yet had the pleasure of meeting, my name is Dorota Blumczyńska and I am the CEO of the Manitoba Museum. I joined the Museum two and a half incredible years ago. I say incredible because my life has been forever changed by what I’ve learned, unlearned, and re-learned in this seemingly short time. Leading this important organization is one of the greatest honours of my career, my life. Every day brings with it new insights, new challenges to overcome, new opportunities to embrace, and new uncertainties to leap into. More about that in a bit.

Why a blog? Although engaging with our communities is an important part of my role at the Museum, it isn’t something I get to do as much as I would like. The day to day realities of leading a museum are dynamic and demanding; they require paying attention simultaneously to what’s on the horizon and what’s right in front of us. I enjoy the challenges that come with supporting a fantastic team and doing hard and heart work, in balance with opportunities to be with the people and planet we do all of it for. That’s where this blog comes in: it’s my way of being present with you, our community, while serving the needs of the moment. In time, as we get to know each other, I hope to hear from you, respond to questions, and offer my insights on museum work and why it matters. These are some of my goals.

So, a little about me. I came to Canada with my parents and four siblings in 1989. We were brought here as Privately Sponsored Refugees – meaning a community who had never met us agreed to support our family during our first years here; everything from finding work, housing, learning English, to understanding our new country. As it is for many migrants, life in Canada in those early years was very difficult. The most basic things proved more complicated than any of us had imagined. In time however, we began to make friends and it was the warmth and welcome of others that helped us feel like we had found home again.

Community, I’ve learned, both professionally and personally, is what makes life a less arduous journey. The mere presence of others, those who witness our milestones, celebrate our successes, grieve our losses, and accompany us in the most beautifully mundane moments, enriches our existence.

My own life was enriched two and half years ago when I was invited to be a part of the Manitoba Museum team.

It was enriched years earlier when my family was selected for re-settlement.

And it continues to be enriched by every chance I get to welcome you, our community, into relationships with us.

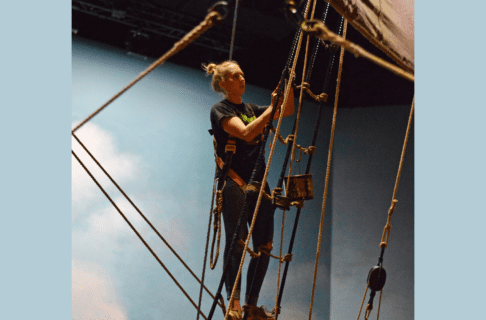

This past year, as you can see from our spectacular new website and changes to many of our physical and online spaces, has been a year of continued transformation. Improvement not for the sake of improving, but with the goal of bringing us closer together, in proximity to each other’s stories.

This CEO corner, the first of many blogs from me to you, will help us get to know one another a bit more, encourage us to be curious about each other’s perspectives, and will create a space where we can ask and answer questions, explore complicated topics, and perhaps, demystify some of the myths and mysteries of museums today.