Posted on: Friday May 10, 2024

Last year the Manitoba Museum piloted a new program to provide community members increased access to Museum collections. Weekday appointments to view collections are sometimes difficult for folks who work full-time or are enrolled in school. This program was developed through discussions with artists, makers, and interested community members. We decided on a free open-access event on a weekend, one where people could sign up and come and spend a few hours looking at many items cared for in storage, rather than on display in the Museum galleries.

Since the majority of the HBC and Anthropology Collections are of First Nations, Métis, or Inuit origin, we structured the initial sessions with preference given to individuals who self-identify as Indigenous. Due to tight collections storage spaces, we kept each session to a maximum of 10 participants. A smaller group setting created a nice, intimate learning environment for discussion, and enabled us to move freely within collection storage as a group.

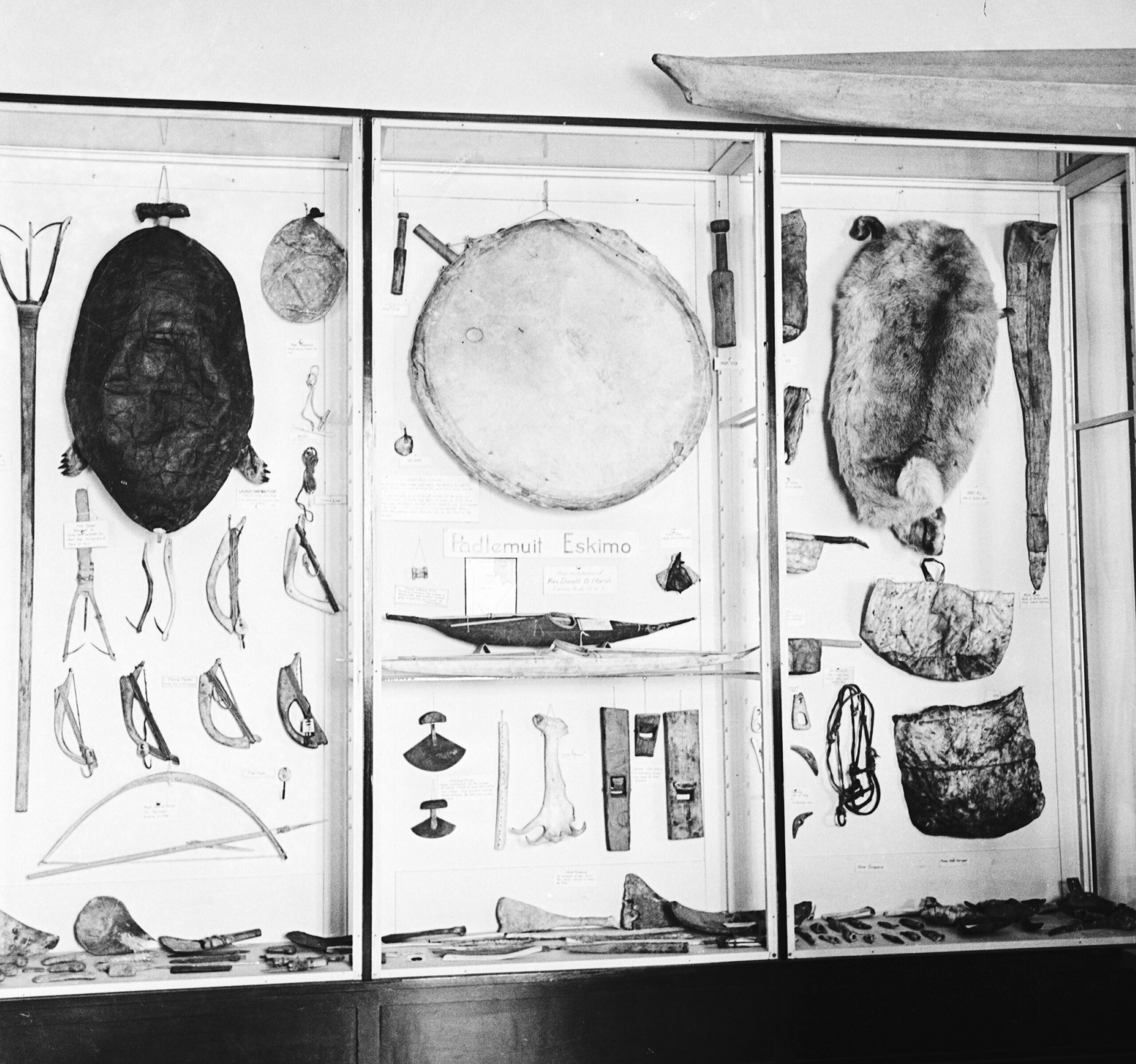

Participants exploring the Anthropology Collection. ©Manitoba Museum

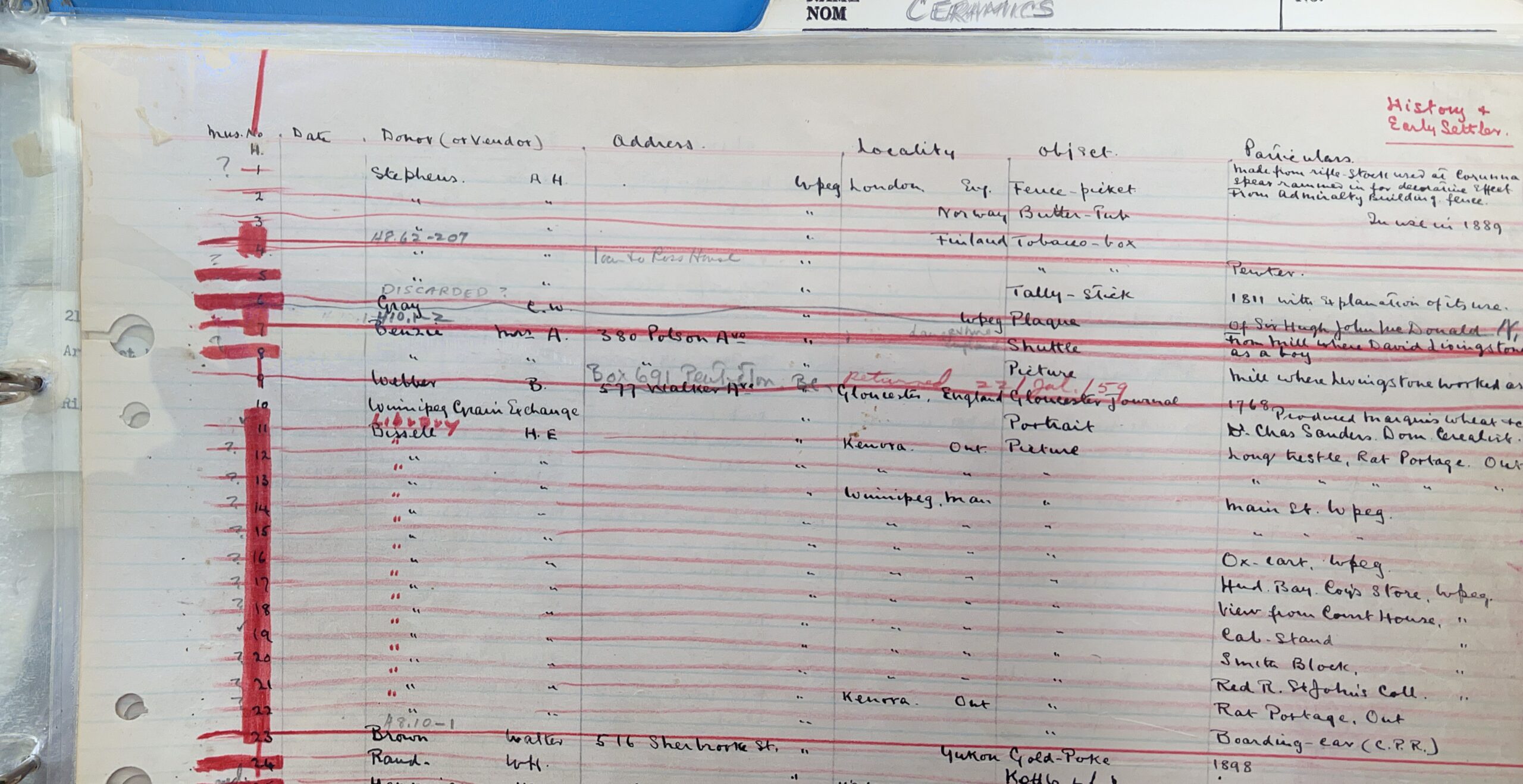

One of many drawers within the HBC Museum Collection featuring wall pockets with beadwork and quillwork. ©Manitoba Museum

For these sessions we brought in skilled artists to discuss the objects with the group and to share learning experiences in traditional artistic techniques. We were very fortunate to feature Jennine Krauchi and Cynthia Boehm at our first session, and Tashina Houle-Schlup and Cheyenne Schlup for the second session. All four of these artists are not only incredibly skilled with beadwork, embroidery, and quillwork in their own artistic practices, but also knowledgeable on historic pieces within the Museum’s collections. Participants were able to learn so much through this collaborative structure with community artists and makers.

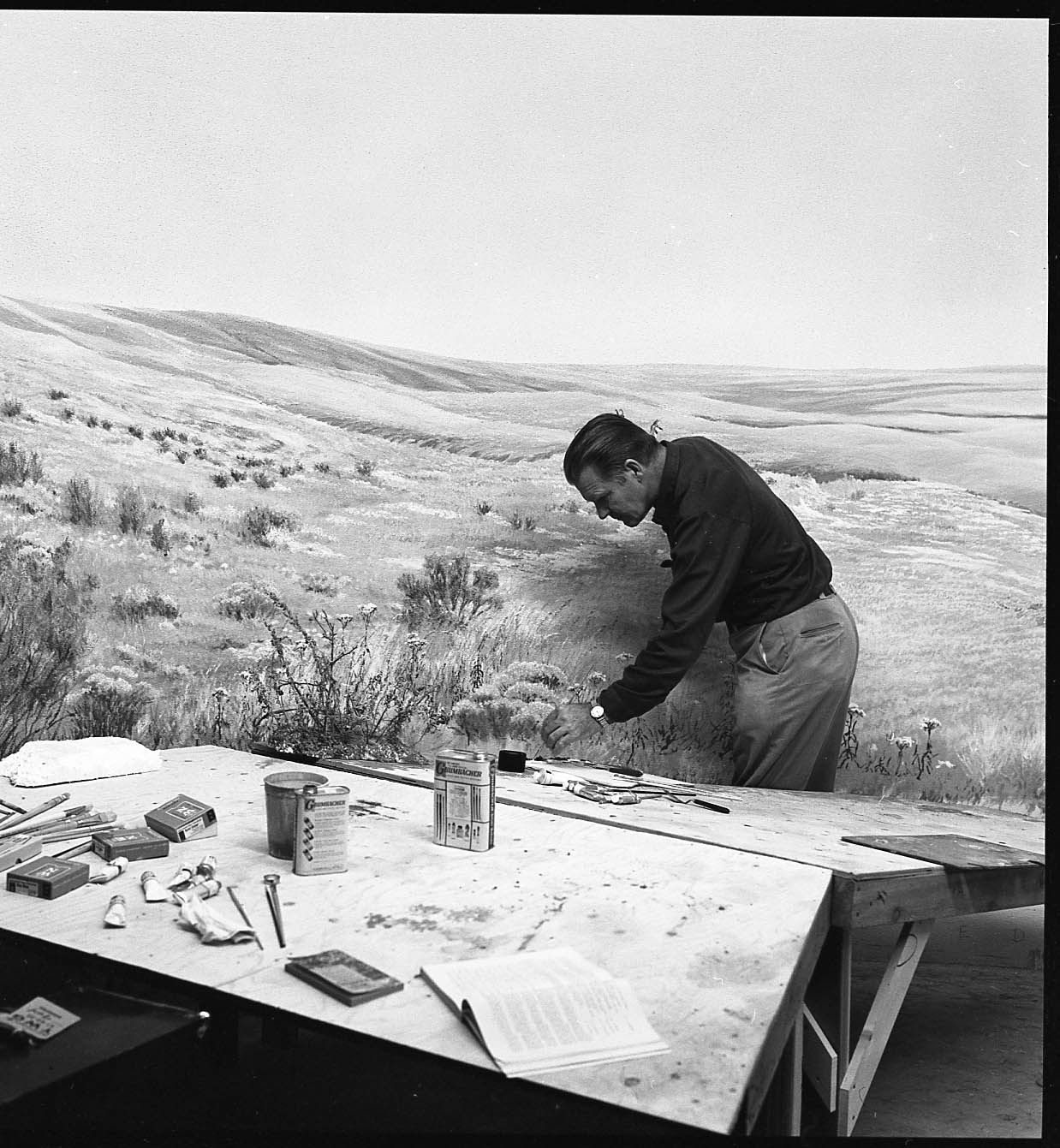

Cheyenne Schlup sharing knowledge with participants (note his beautiful work in the background). ©Manitoba Museum

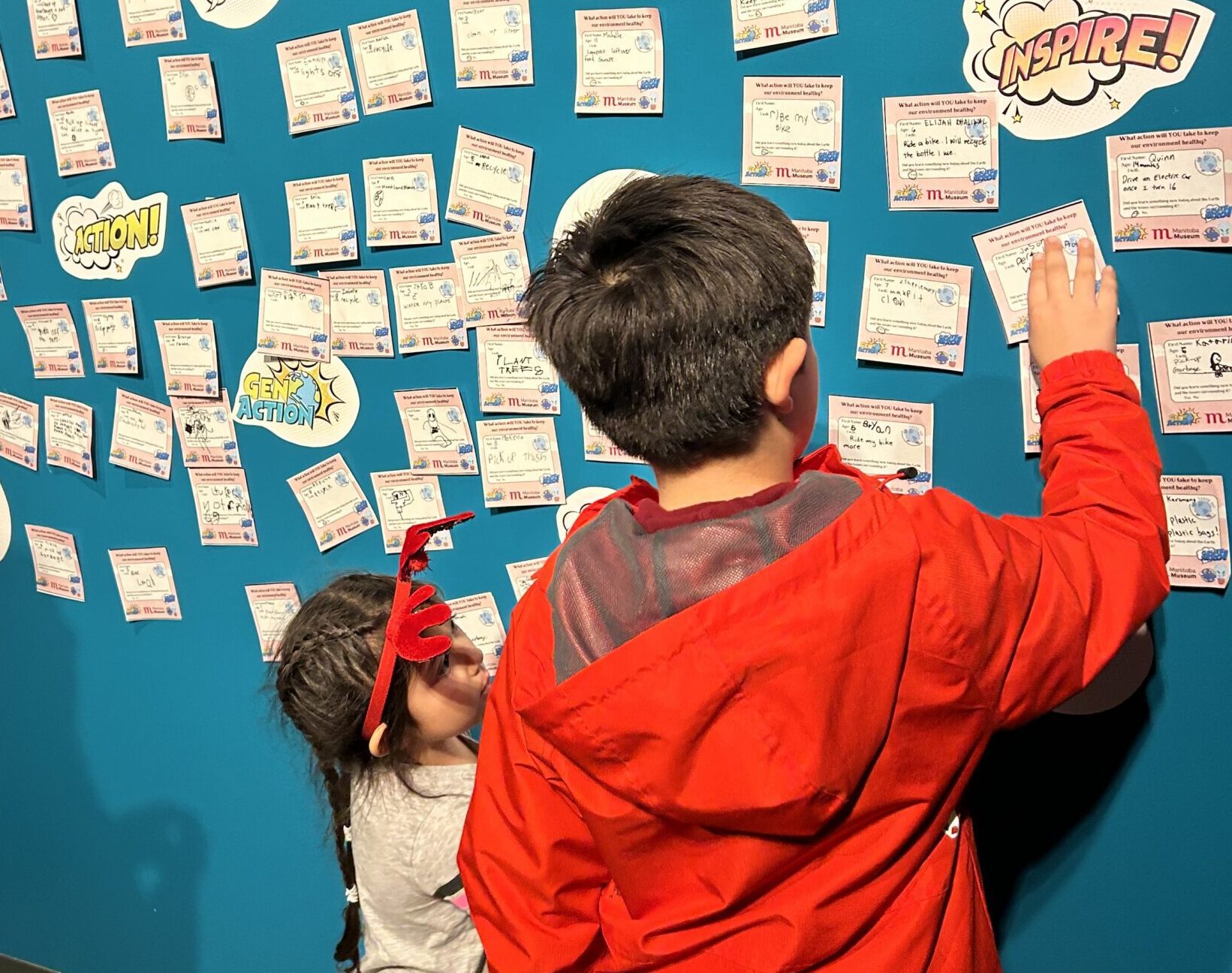

Artist Jennine Krauchi shows session participants several beautifully beaded artifacts stored with care ©Manitoba Museum

Based on the success of this program last year, we hope to offer 3-4 more sessions in the upcoming year, featuring different artists to share these wonderful collections with interested community members. If you’re interested in participating, keep your eyes on the Museum’s website and social media for the next session!

Don’t miss out on our special Mother’s Day tour From Talk to Table: Indigenous Motherhood on May 12. This tour explores parenting throughout time on Turtle Island and includes include an in-depth tour of Indigenous artifacts in the Museum Galleries and behind-the-scenes.