Posted on: Tuesday May 27, 2025

Spring has finally arrived on the prairies! Trees are leafing out, flowers are in bloom, days are getting hotter, and, of course, the insects are back! They’re flying, swimming, and crawling around, playing important ecosystem roles that make the world go ‘round. While you can always come to the Museum to see the insect specimens that we have on display in the Museum Galleries, nothing beats the real live thing. But what’s the best way to get a good look? Take it from your Collections Technician for Natural History, if you want to see some cool insects, nothing beats night lighting.

What is night lighting?

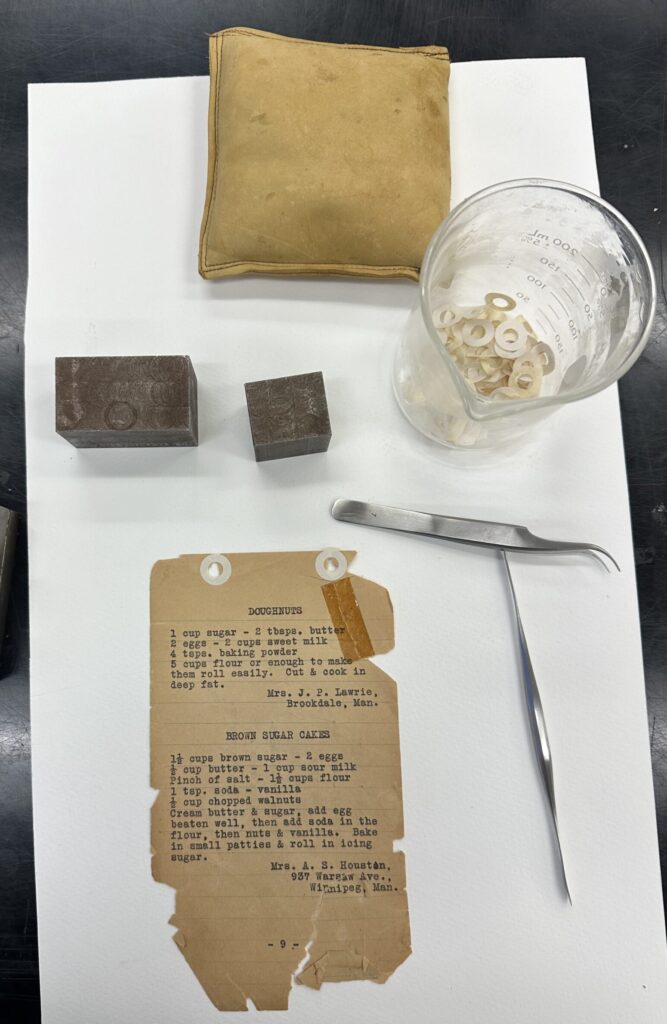

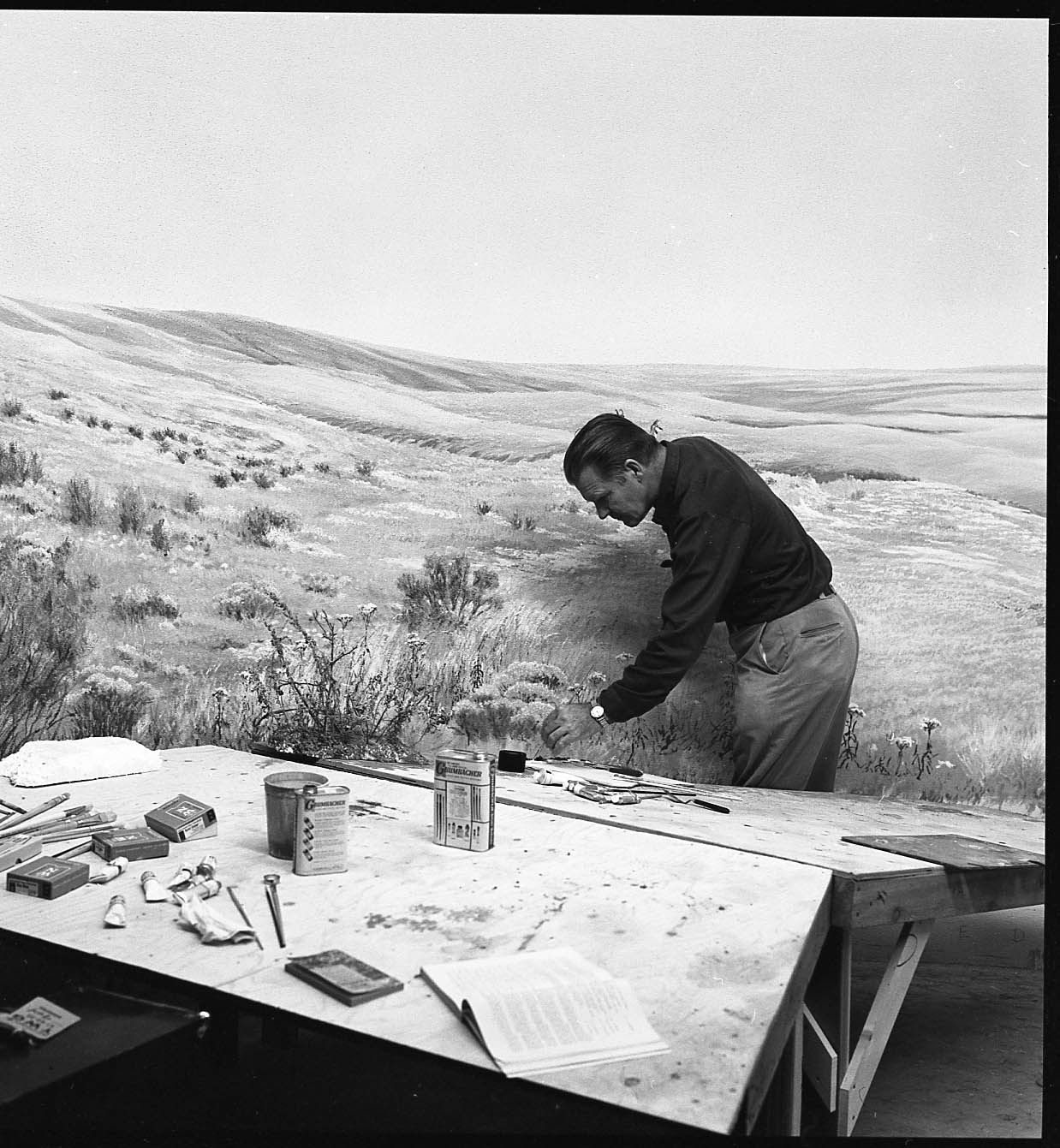

The words “Night lighting” on appear on data labels for specimens throughout our entomological collection, but what does it mean? “Night lighting” is the use of light sources at night to attract insects for observation, photography, or collection. When a specimen has “Night lighting” on the label, it means that the collector set up a night light to catch the specimen. While serious entomologists use expensive rigs involving power generators and mercury vapour lamps, low-cost setups can be put together easily, with supplies you likely already own or can get at a hardware store. Once you’ve got your kit together, you can set it up in your yard, at a city park, or even take it camping!

Here’s what you need to get started:

- A white sheet, the bigger the better

- A regular flashlight, the brighter the better

- An ultraviolet flashlight (AKA blacklight), the broader the UV spectrum the better

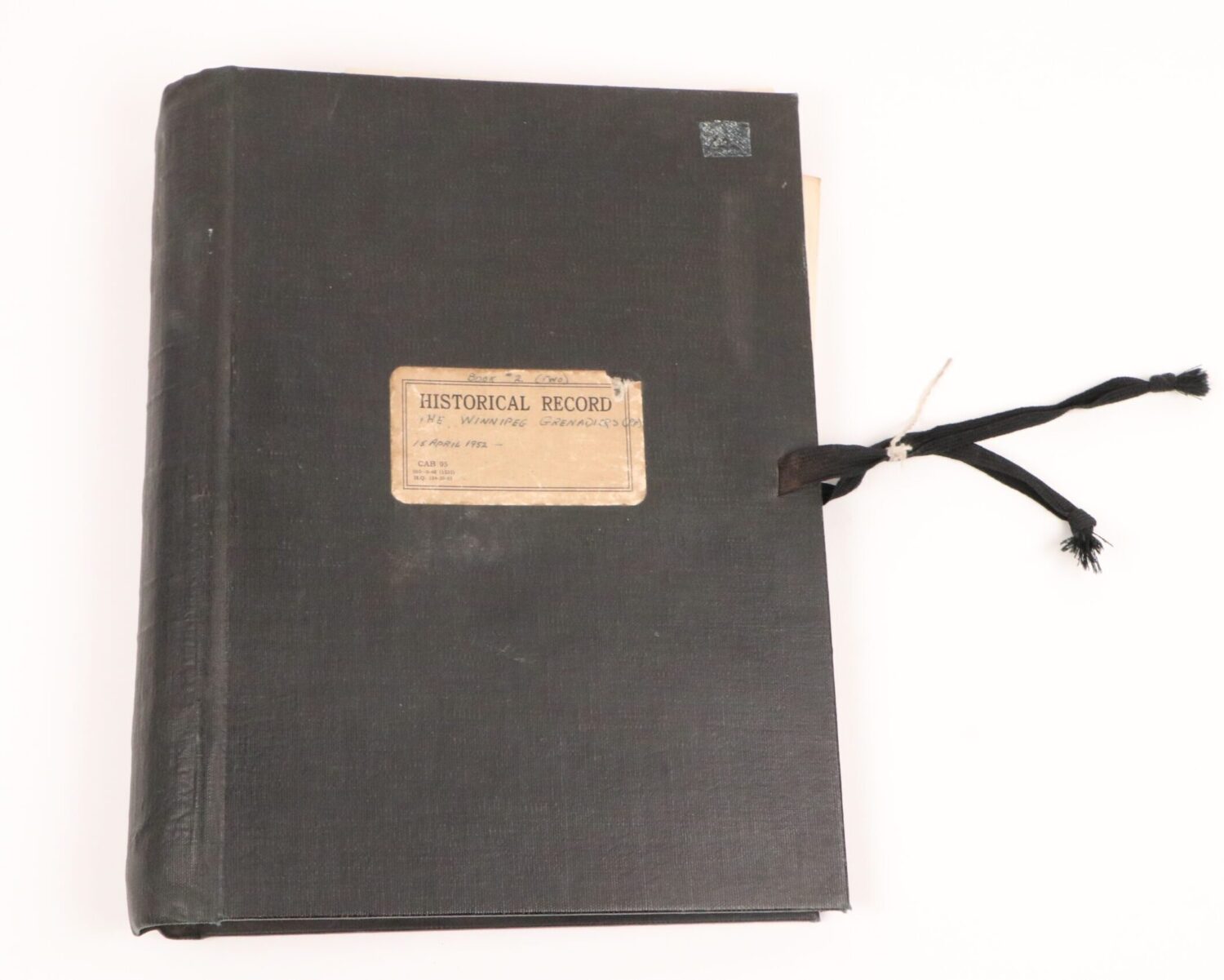

A professional night lighting setup, sometimes they attract humans too!

A backyard bug night light set up.

Basic UV flashlights can be purchased in many hardware stores, and ones that emit a broader spectrum of UV light can be found online. A quick safety note: UV light can damage the skin and eyes. Do not look directly into the light, and limit skin exposure by avoiding the beam and wearing long pants and sleeves.

Once you have your supplies, wait for a warm evening with low wind and no rain. Drape the sheet over a low-hanging tree branch, a fence, or anything else that’s handy. It’s best to hang the sheet low enough that a little bit of it can trail out over the ground, allowing crawling insects to climb up from the bottom. Set both flashlights on an elevated surface where they can shine at the middle of the sheet, and turn them on as the sun is setting. Soon enough, insects in the area will land on sheet so you can get a good look!

Image: A badly-lit and somewhat blurry Collections Technician waiting for the insects to hurry up and get to the party!

A Family Friendly Activity

Now, I know some readers are probably thinking “Why would I want to attract insects? Will they bite? Is this safe?”, and to that I would say: Using a night light to attract insects is a really excellent way to get up close and observe some of Nature’s coolest critters, even for those who are skittish around insects. Once the insects are on the sheet, they tend to stay on the sheet, and if they do take off, they’ll be much more interested in getting back to the sheet than investigating you! Since the insects are so preoccupied with getting to and staying on the sheet, it makes for a controlled way to introduce young ones to insects and teach them about the creatures they find. Here are some common insects to find at light traps in the city:

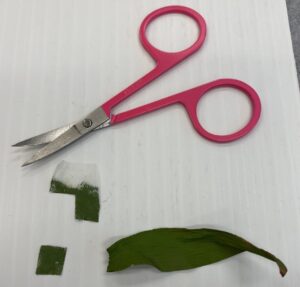

Crane flies:

These insects have been the subject of salacious urban legends! Some say they are male mosquitoes, others call them “mosquito hawks” and claim that they devour mosquitoes, and others yet claim that they have an extremely potent venom that could take out a human in a single bite if only their fangs were long enough to break human skin. None of these rumours are true! Crane flies (which aren’t mosquitoes) are flies from the superfamily Tipuloidea, known for having legs and wings that are notably long and slender. They eat nectar and pose a threat to neither humans nor mosquitoes.

Image: A crane fly.

Moths:

Moths, famous for their attraction to lamps and flames, are never late to the night light party. Many moths that appear to be drab shades of gray and brown during the day shimmer and shine under a bright light at night!

Image: A moth (and friends), shimmering under the bright lights.

Caddisflies:

These insects resemble moths at first glance, but if you see extremely long antennae compared to their body length, you might be looking at a caddisfly. On closer inspection, their wings are covered in fine hairs, rather than the scales that are found on moth wings. Caddisflies start their lives underwater and take to the skies as adults.

Image: A caddisfly with its very long antennae.

Stoneflies:

Similar to caddisflies, stoneflies are aquatic in their early life stages, and fly around to look for mates as adults. They can be identified by a pair of thin cerci (tail-like structures) extending from the end of the abdomen, and the way they hold their wings flat over their backs when at rest.

Image: A stonefly (if you look closely, you can see the cerci coming out from under the wings).

Gather your supplies and give night lighting a try this summer! Happy bug hunting!