December provides long winter nights for observing and features the best meteor shower of the year as well as the return of the winter constellations to early evening prominence. Colder temperatures can make observing more difficult, since astronomy is not an aerobic activity! Dress in layers, and plan for a temperature at least 10 degrees colder than the forecast. Good boots and a warm hat are the most important accessories.

Visible Solar System

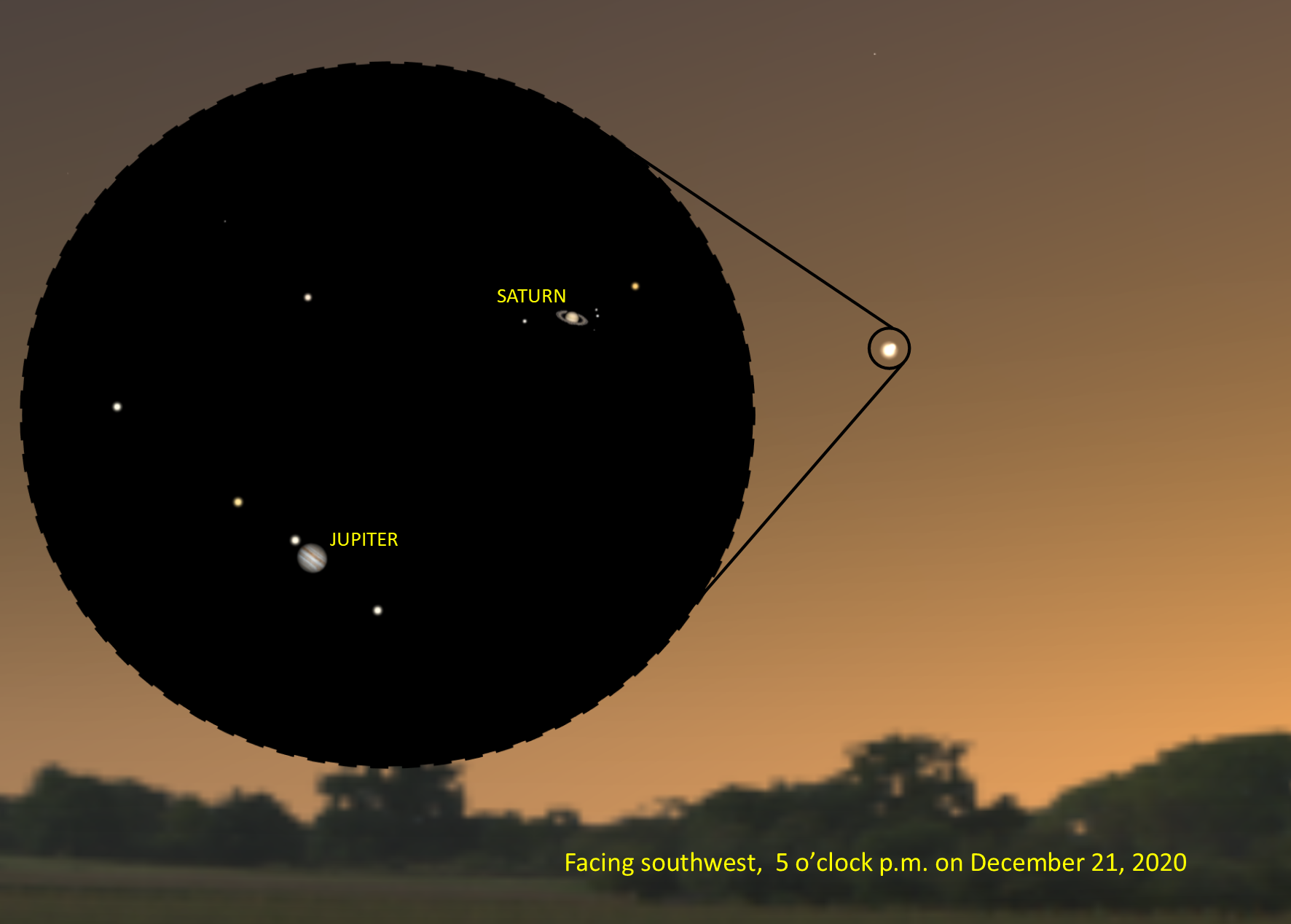

Saturn is nearly gone, low in the southwest after darkness falls. This hasn’t been a great year for observing the ringed planet since it has been so low in the sky from Manitoba.

Jupiter is already fairly high in the east-southeast as darkness falls, and rises into the south by mid-evening, providing clear views for Canadian observers. Binoculars show several of its four largest moons, and a telescope will reveal cloud bands and structure in the gas giant planet’s atmosphere.

Venus rises about 4 a.m. local time at the beginning of December. It stands about 20 degrees up in the southeast before dawn but rises later and loses altitude throughout the month.

Mercury begins to creep above the eastern horizon at dawn towards the end of the month but is more easily visible in the first week of January. Even so, Manitobans will have a tough time spotting it in the bright twilight just before sunrise. We’ll have a better chance in March when Mercury is visible in the evening sky.

Mars is on the far side of the Sun this month, too close to the Sun to be visible in the morning sky.

Calendar of Celestial Events

(All event dates and times are local times for Manitoba – Central Standard Time. Almost all events are visible across Canada, though – just use your local time instead. The exception is an event like the Solstice or a specific phase of the Moon, which happens at a specific time and date. In those cases, you have to adjust to your local time by adding or subtracting time zones.)

Mon 4 Dec 2023: Last Quarter Moon occurs just before midnight Manitoba time tonight, so many calendars that use Eastern Time or Universal/Greenwich Time will show it on Dec 5th instead.

Sat 9 Dec 2023 (morning): The waning crescent Moon is 4° to Venus’ lower right.

Tue 12 Dec 2023: New Moon

Wed 13 Dec 2023 (evening) through Thu 14 Dec 2023 (Thu): The annual Geminid meteor shower peaks overnight, with the nearly new Moon providing dark skies. With a theoretical rate of over a hundred meteors per hour for most of Canada, this is the meteor shower to see. You’ll want to get to dark rural skies and be well-prepared for a long night of winter observing. Pay particular attention to your vehicle if the temperatures are low, as being stuck in the middle of nowhere on a cold December night can be dangerous.

The Geminids are also one of the few meteor showers that are active before midnight, making them a bit more accessible than other showers such as the Perseids in August, which are at their best in the few hours before dawn. For details on how to turn your meteor watching into scientifically useful data, visit the International Meteor Organization’s Geminid page.

Sun 17 Dec 2023 (evening): The waxing crescent Moon is about 3° below Saturn.

Tue 19 Dec 2023: First Quarter Moon

Thu 21 Dec 2023 (evening): The waxing gibbous Moon is far to Jupiter’s right.

Thu 21 Dec 2023: Also tonight, the winter solstice occurs at 9:27 p.m. CST, marking the sun’s farthest movement south in our skies. This translates into the late sunsets and long winter nights of winter. After this date, the sun will rise earlier each day, and the number of daylight hours will begin to increase.

Fri 22 Dec 2023 (evening): The waxing gibbous Moon is far to Jupiter’s left.

Tue 26 Dec 2023: Full Moon

Thu 28 Dec 2023 (evening): The Manitoba Museum’s award-winning online astronomy show Dome@Home airs at 7 p.m. CST, live on the Museum’s Facebook and YouTube pages. Dome@Home covers the celestial sights and events visible in the coming month, and highlights some of the cool space stuff that’s happened in recent weeks.

Sun 31 Dec 2023: The last day of the Gregorian calendar which is used in most parts of the world including Canada.

To find when the International Space Station and other satellites are visible from your location, visit Heavens-Above.com and set your location.

For information on Manitoba’s largest astronomy club, visit the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada – Winnipeg Centre.