Posted on: Friday May 11, 2012

By Kevin Brownlee, past Curator of Archaeology

On day 7 Myra and I awoke to another beautiful day. We decided that we would complete all the sewing, attaching the gunwale caps and final trimming but would not pitch the canoe. Grant had offered to complete this last stage after we returned to Winnipeg.

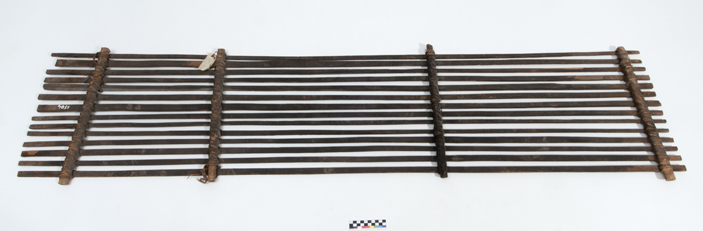

We all marvelled at the beauty of the canoe now that it has the final shape. It is amazing that in one week we could turn bark and wood into such an amazing watercraft. Clearly there is nothing “Printive” about a birch bark canoe. Grant spoke about how when Europeans arrived to North America they came from a long tradition of boat building. However Europeans found them unsuitable to the navigate the waterways of the boreal forest and quickly adopted the birch bark canoe.

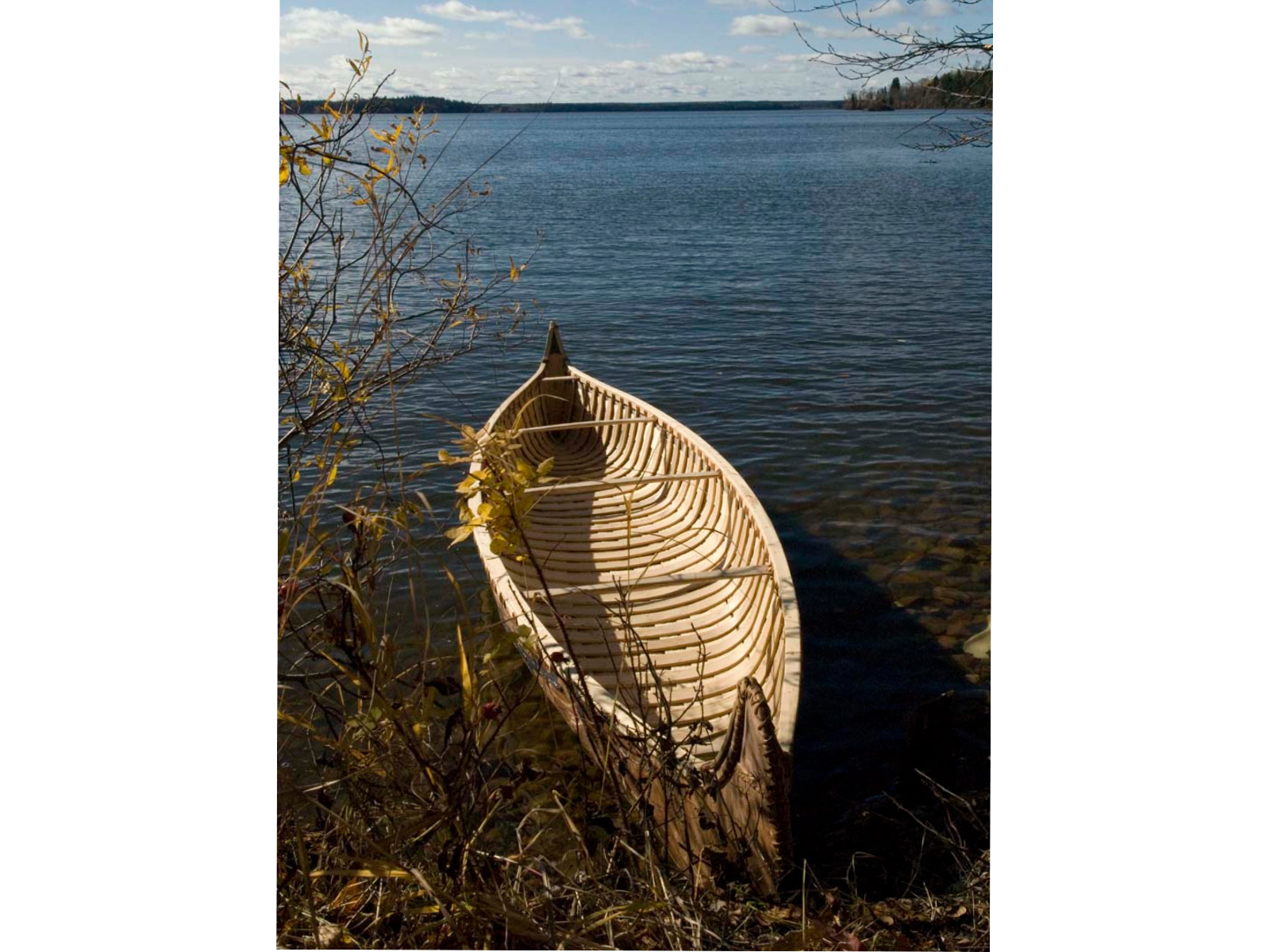

Unpitched canoe 15 feet long.

Kevin, Grant, and Myra by the our canoe.

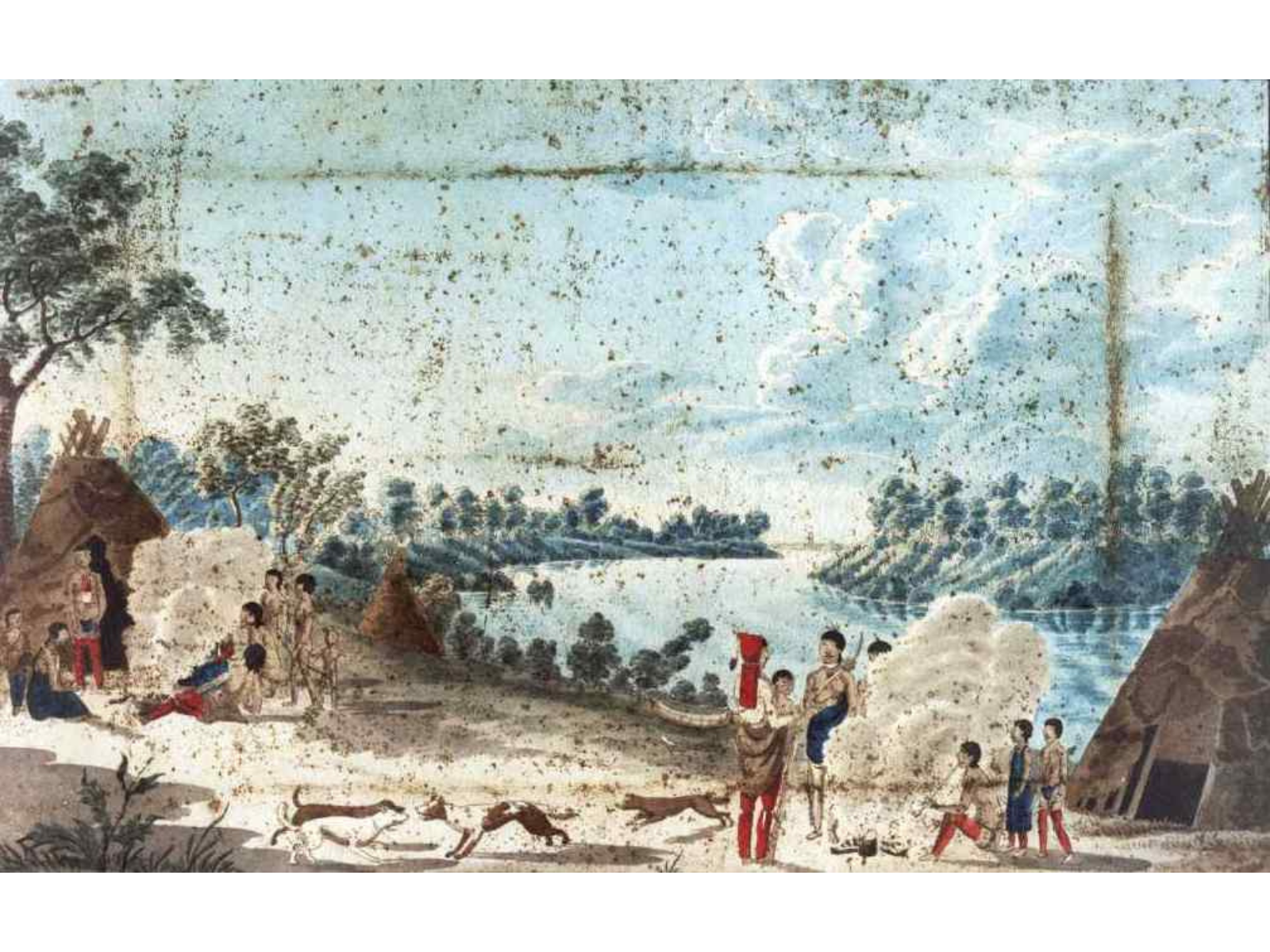

Later that Fall on a vacation from the office I took the canoe into northern Manitoba for the inaugural launch into the clear waters of the Canadian Shield. Paddling on the lake I realized this is probably the first time in over a hundred years that anyone has paddled a birch bark canoe in the area. What an amazing gift from relatives from the south.

Canoe pulled up on shore.

First Paddle.