Posted on: Wednesday September 18, 2013

By Dr. Graham Young, past Curator of Palaeontology & Geology

Following on from my recent post about the geology of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, it seems entirely appropriate timing that another piece of architectural geology work has just been published. Last week, a guidebook to the geology of the Manitoba Legislative Building, by Jeff Young, Bill Brisbin, and me, finally appeared in downloadable form. The entire file (20 megabytes) can be found here.

The Manitoba Legislative Building (photo by Jeff Young).

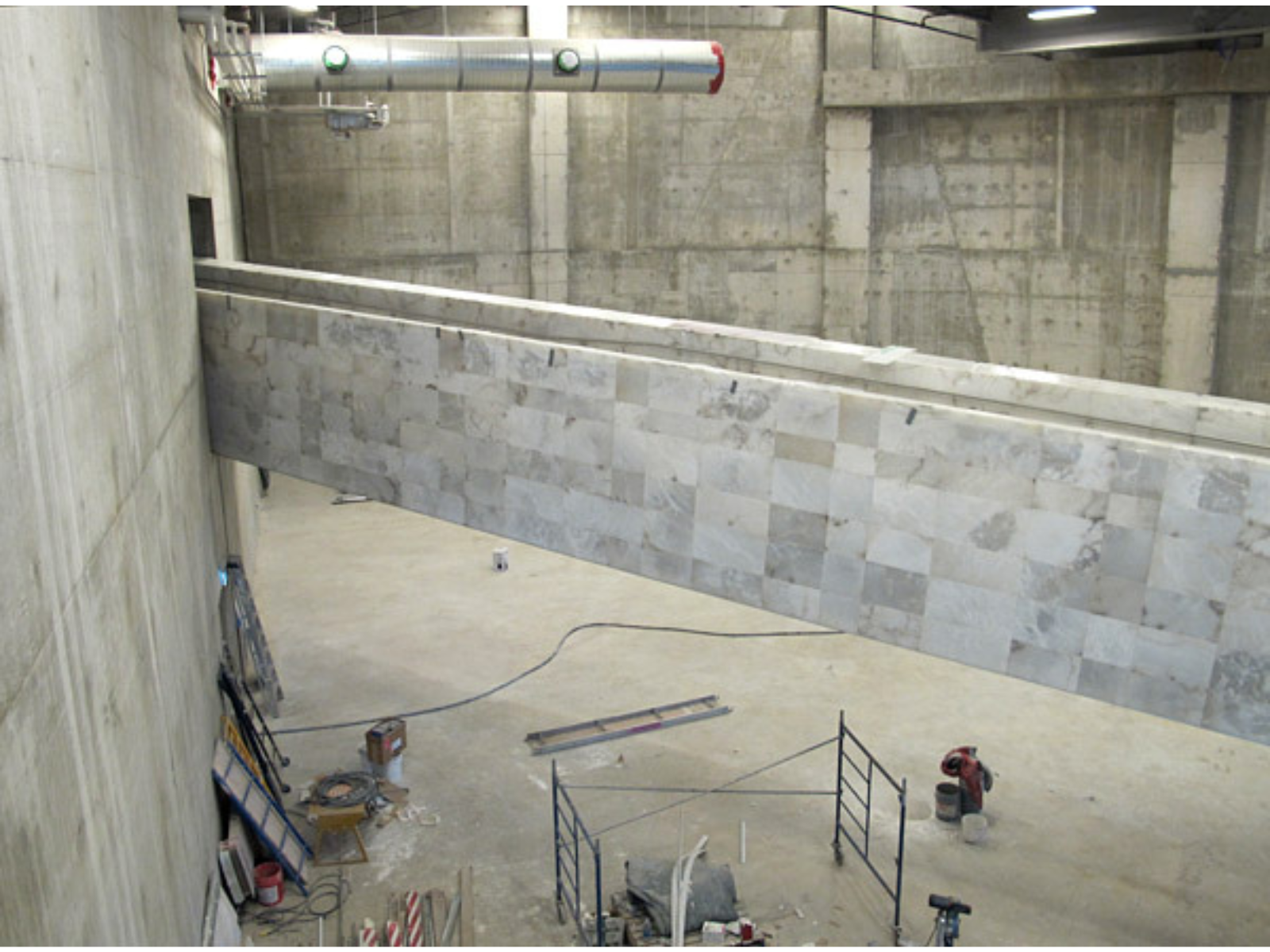

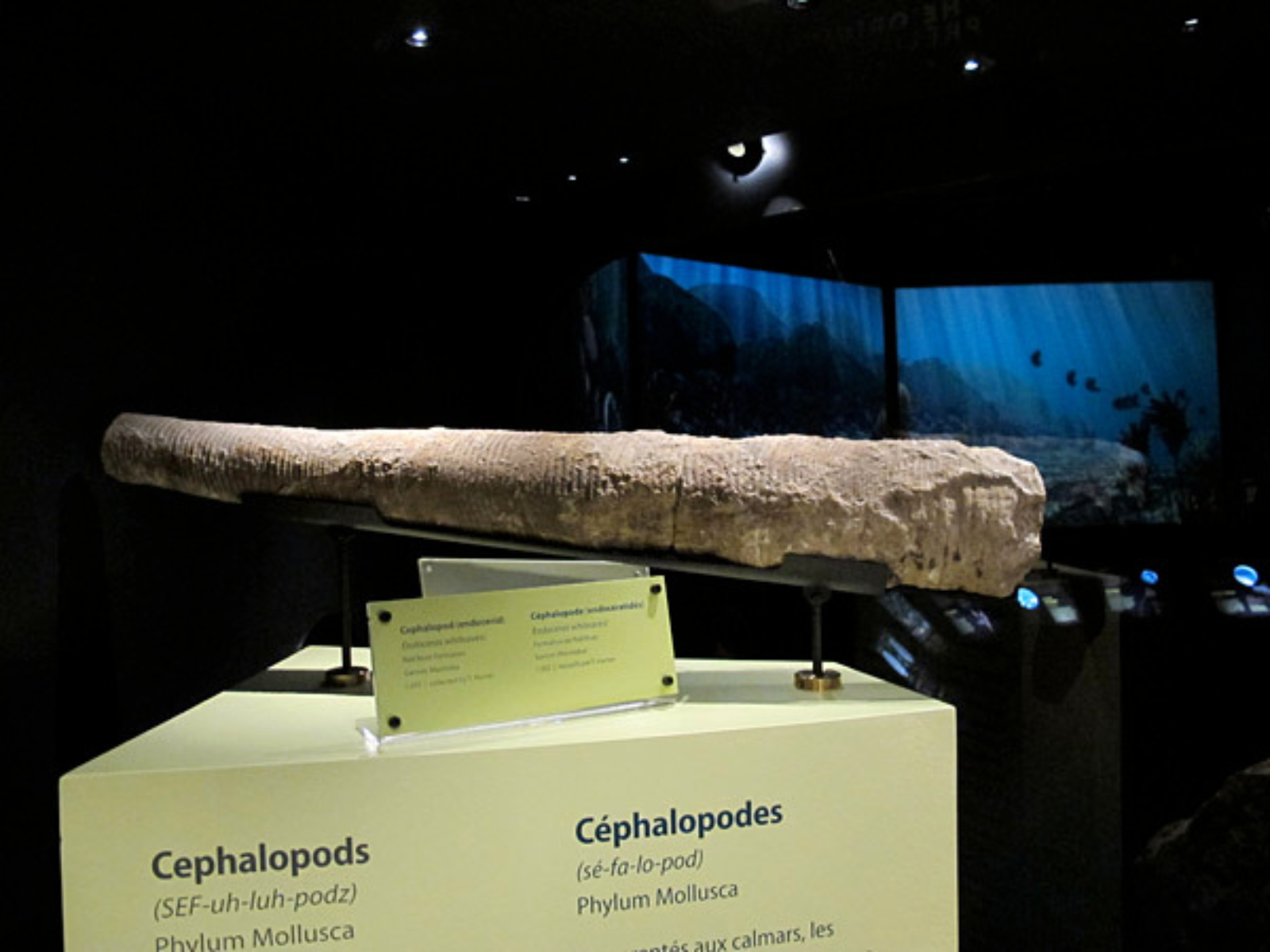

The Rotunda inside the Manitoba Legislative Building features walls of Manitoba Tyndall Stone, and floors of Tennessee marble, Verde Antique marble, and Ordovician black marble.

This book was published as part of a series of field trip guides for the Geological Association of Canada – Mineralogical Association of Canada annual meeting, which took place in Winnipeg in May. Jeff Young (University of Manitoba) and I had the pleasure of leading an afternoon tour of the Legislative Building; it is such an interesting and beautiful structure, and it is always a pleasure to see people’s reactions to its geological features. The guidebook is based on research Jeff and I did with Bill Brisbin (also of U of M) almost a decade ago.

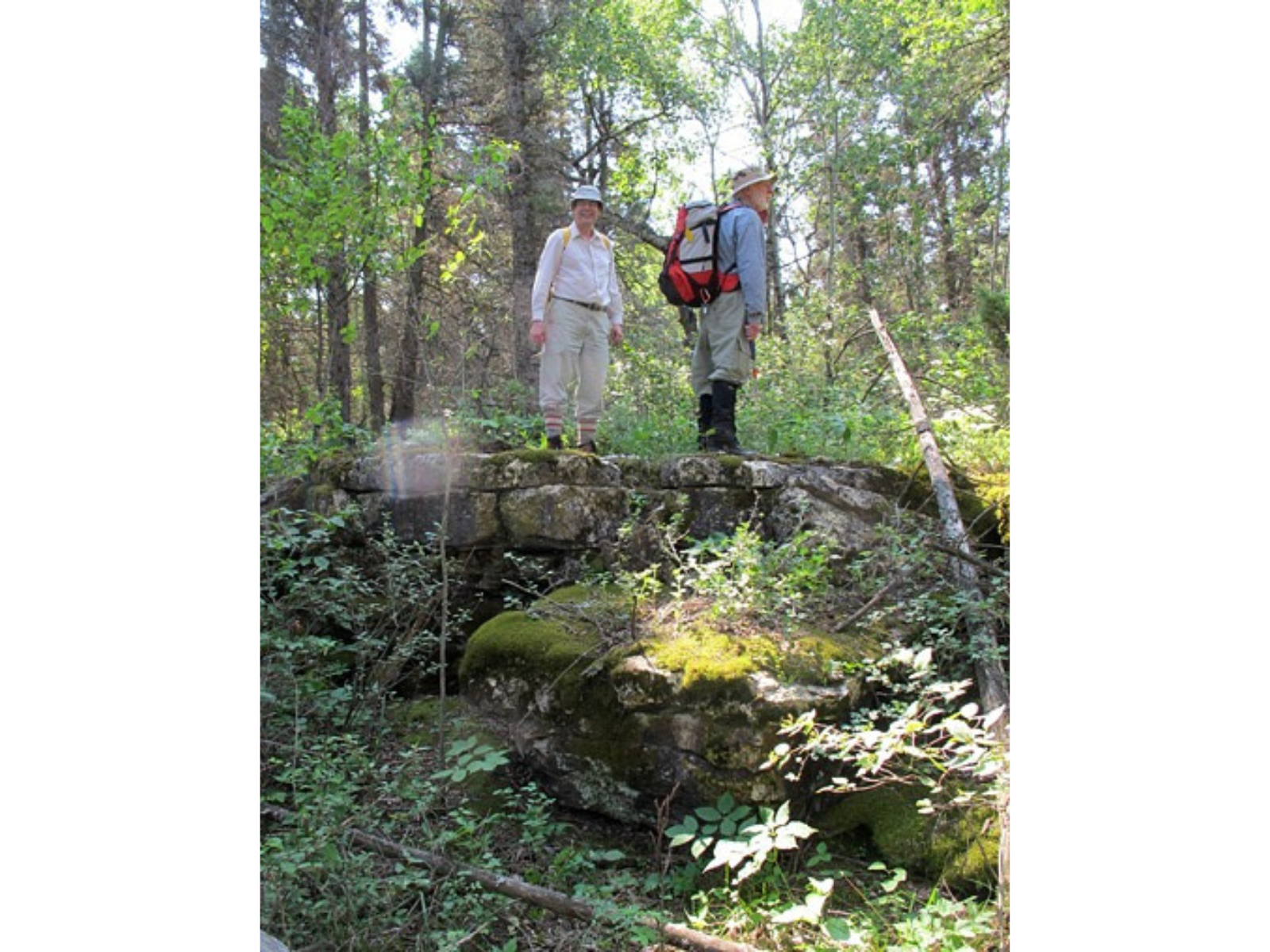

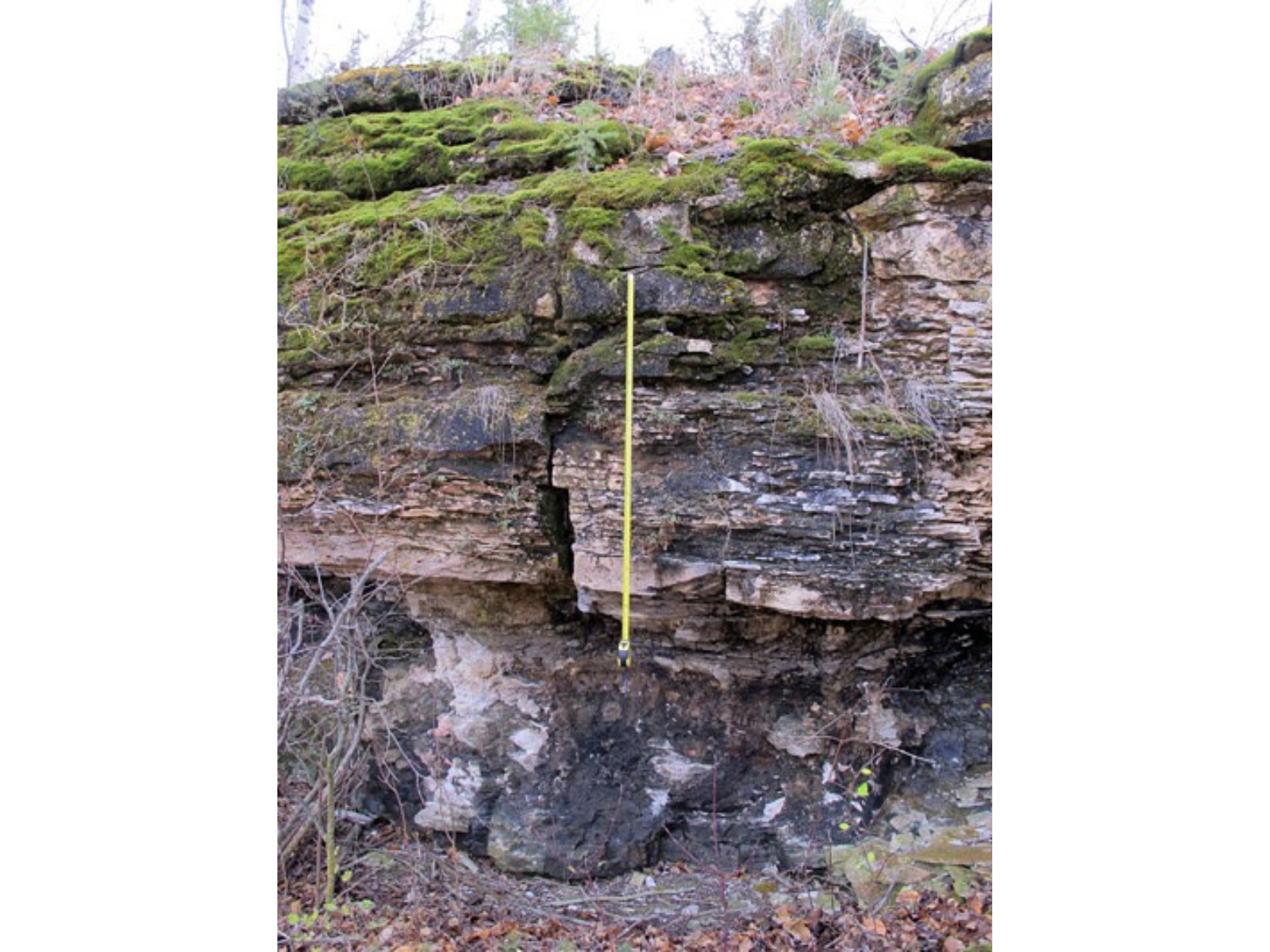

In addition to the Legislature guidebook, I also enjoyed assisting with a field trip on the Ordovician to Silurian geology of southern Manitoba. The guidebook for that trip (26 megabytes), by Bob Elias et al., can be downloaded here.