Posted on: Monday April 7, 2014

I’m sure I don’t have to tell anybody this, but this winter has been brutally cold—the coldest winter in 35 years! Every time it seems like we are finally going to get some warmer temperatures, we are plunged back into a deep freeze. Luckily, for most of us, we are able to put on layers of warm clothing to protect ourselves from the elements. Down-filled jackets and Gore-Tex might be considered, quite literally, lifesaving materials. However, even without these innovations, people have survived in North America for thousands of years. Have you ever stopped to think about the clothing people wore in the past to help them to survive such harsh winters?

As we see in the Aschkibokahn mini-diorama, mobility was essential to survival for many First Peoples. The mini-diorama shows the seasonal movements of an Anishnaabe family. Their clothing had to offer protection against the elements, but also had to be easy to move around in. For much of the year, the clothing didn’t have to be exceptionally warm. A great deal of Anishnaabe clothing used tanned deer and moose hides. Hides were useful for clothing because the material is strong but pliable and resilient. As winter approached, people needed warmer clothing to help survive the elements.

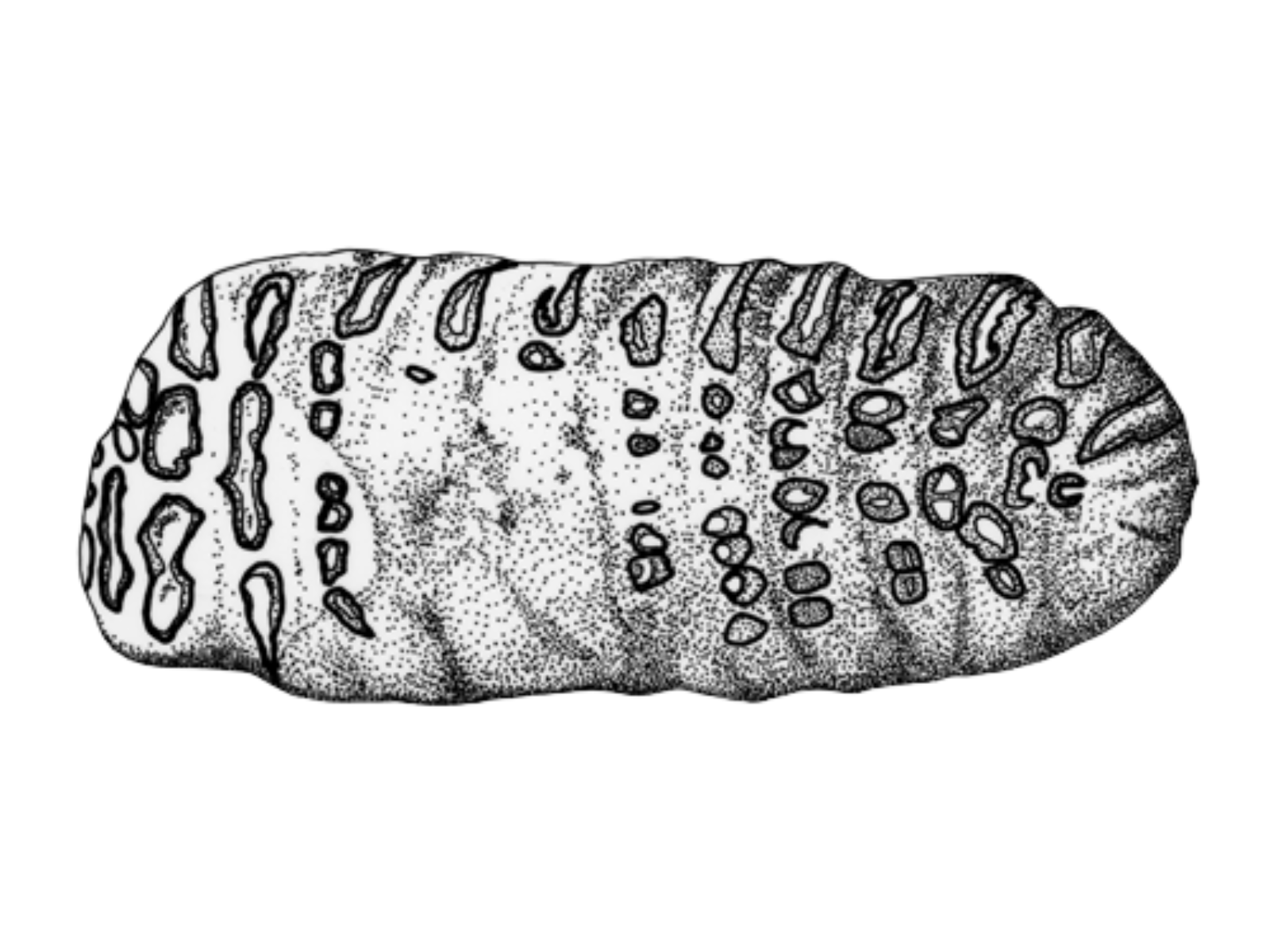

Image: A child wearing woven rabbit skin parka in the Aschkibokahn mini-diorama.

For this purpose they made garments and sleeping bags out of thickly woven rabbit fur. It takes many rabbit hides, cut into thin strips to make these garments but they are very warm. If you take a look at the winter scene in the diorama, you can see that Betsy (the diorama artist) has outfitted some of the family in rabbit fur coats. Betsy’s attention to detail serves to help the visitor accurately imagine what life was like for this family. Further, it goes to show that the people who lived in the area made good use of the materials available to them in order to survive winters in a way. It is remarkable to think that people could not only survive, but thrive in this climate without any of our modern luxuries.

Deer Lake Group, [circa 1925]. Archives of Manitoba, Still Images Section. R. T. Chapin Collection. Negative 15148.

Speaking of harsh winters, ours is still not over yet. While you’re waiting for it to warm outside, why not come inside to the museum to check out the mini-diorama for yourself?

In 1993, the remains of a woman were found at Nagami Bay (Onākaāmihk) west shore of Southern Indian Lake. The following year, community members from South Indian Lake and archaeologists worked together to recover our ancestor in a respectful and honourable way. The story of her miskanow, life journey, was pieced together from her remains and her belongings and told in the book

In 1993, the remains of a woman were found at Nagami Bay (Onākaāmihk) west shore of Southern Indian Lake. The following year, community members from South Indian Lake and archaeologists worked together to recover our ancestor in a respectful and honourable way. The story of her miskanow, life journey, was pieced together from her remains and her belongings and told in the book