Posted on: Tuesday July 24, 2012

By Dr. Graham Young, past Curator of Palaeontology & Geology

If you visit this page occasionally and have been wondering about when the next blog post would be forthcoming, well, I had been wondering that too. I have begun new posts several times, but in each instance my focus has been pulled away by the same all-consuming activity: my time has been taken up by the completion of a mineral exhibit. This past week, we finally did the installation, so I thought I had might as well set those posts-in-progress aside yet again. Here, instead, are some photos of the exhibit.

Collections specialist Janis Klapecki and designer Stephanie Whitehouse work on the final location of one of the plexiglas specimen mounts.

At the Museum we had long recognized that a mineral exhibit was one of the features most lacking in the Earth History Gallery. Minerals are the basic building blocks of rocks and other geological materials, we have a great diversity of minerals in this province’s rocks, and of course minerals are often beautiful objects that are treasured by many collectors.

For the past several years we have been collaborating with the Mineral Society of Manitoba to acquire specimens suitable for exhibit, and The Manitoba Museum Foundation and the Canadian Geological Foundation had kindly provided us with funding to construct cases. This exhibit is at the front end of the Earth History Gallery, where we only had space for a couple of cases, and the number of specimens and volume of text were quite limited, so this should have been a simple little exhibit project, no?

The giant amethyst now has its own gallery case (in the next post I will tell you how we got it there!).

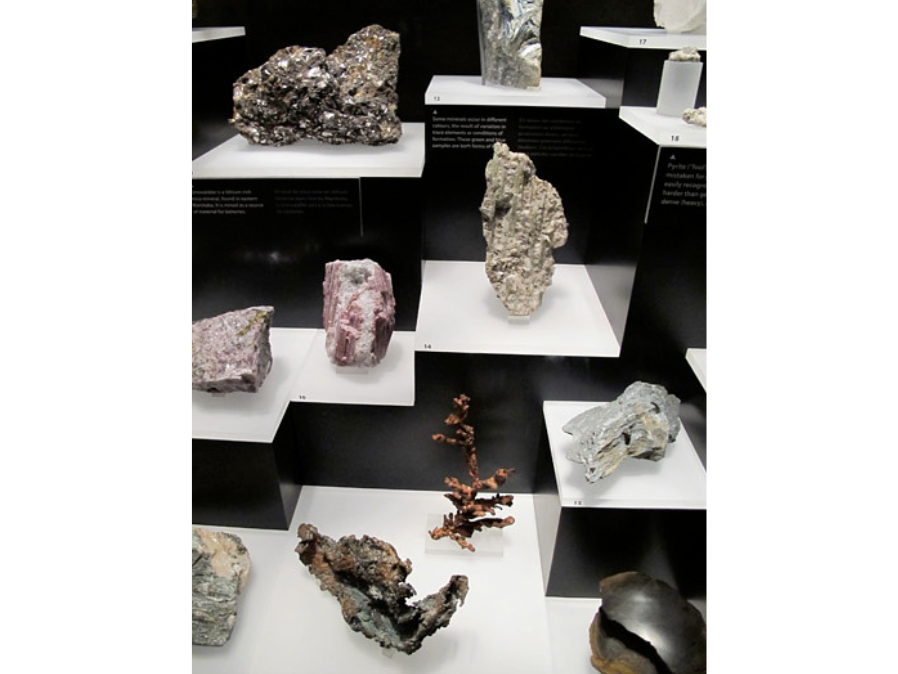

Beryls from eastern Manitoba (top), along with pyrites, feldspars, and base metal ores.

No. Things are never simple when you have to develop an exhibit from scratch. And in this particular instance our design and exhibit staff were working to develop techniques that we had not tried before. We had examined mineral exhibits in many other places (both in-person and through photographs) and had decided that we needed dark cases with the light really focused on the specimens.

Image: The mid part of the case features a variety of minerals, including a Tanco rubellite (donated by Cabot Corporation) and samples of beautiful Michigan copper (the tree-like specimen was acquired and donated by the Mineral Society of Manitoba, John Biczok, and Tony Smith).

Stephanie Whitehouse, our designer, wanted to try working more with metal and glass on this case, and she asked the workshop to look at ways plexiglas could be prepared to allow it to glow. Bert Valentin considered new lighting options (though he eventually settled on fibre optics similar to those in the Ancient Seas cases) and Marc Hébert had to develop new techniques to build cases using different construction materials. Lisa May and Wayne Switek constructed specimen mounts that look simple but had to hold the specimens just so. And once all the pieces were constructed, it still took the team most of last week to assemble them and make everything fit. Dealing with the giant amethyst (now informally rechristened The Mammothist) was a big piece of this process, so big that I will give it its own post in the near future!

This splendid millerite is from Thompson, source of some of the best examples of this unusual nickel mineral. It was acquired for the exhibit by the Mineral Society of Manitoba and The Manitoba Museum Foundation. (catalogue number M-3596)

If you visit the Gallery you will still see the old exhibits between the mineral cases and Ancient Seas, but the space is starting to develop quite a different feel.

For the first time ever, the Earth History Gallery has a title!