Posted on: Tuesday October 1, 2013

By Dr. Graham Young, past Curator of Palaeontology & Geology

I have often been told by members of the public that, “it must be so exciting to do paleontological fieldwork.” This is true, it can be very exciting to visit new places, to discover and collect fossils that were previously unknown to science. But often the conditions are such that the fieldwork is more of a necessary evil. It is a step that must be passed to acquire essential specimens, rather than a pleasure in itself.

Last week was a case in point. I had planned to travel to the Grand Rapids Uplands of central Manitoba with Dave Rudkin (Royal Ontario Museum) and Michael Cuggy (University of Saskatchewan) to carry out a bit of additional collecting at some unusual fossil sites. We had chosen late September because (1) the weather is often dry and clear, and (2) the mosquitoes and blackflies have generally been depleted by this time of year.

It turned out that we were only partly right on just one of these assumptions: I don’t think I saw a single mosquito. Their absence was, however, compensated by the swarms of blackflies that descended whenever the wind died down. And that merciful wind was a chill, damp one, associated with rains that were at times heavy.

Scraping away the inch of mud adhering to my knee pads (photo: Dave Rudkin, Royal Ontario Museum)

Michael contemplates water “ponded” on the bedrock surface.

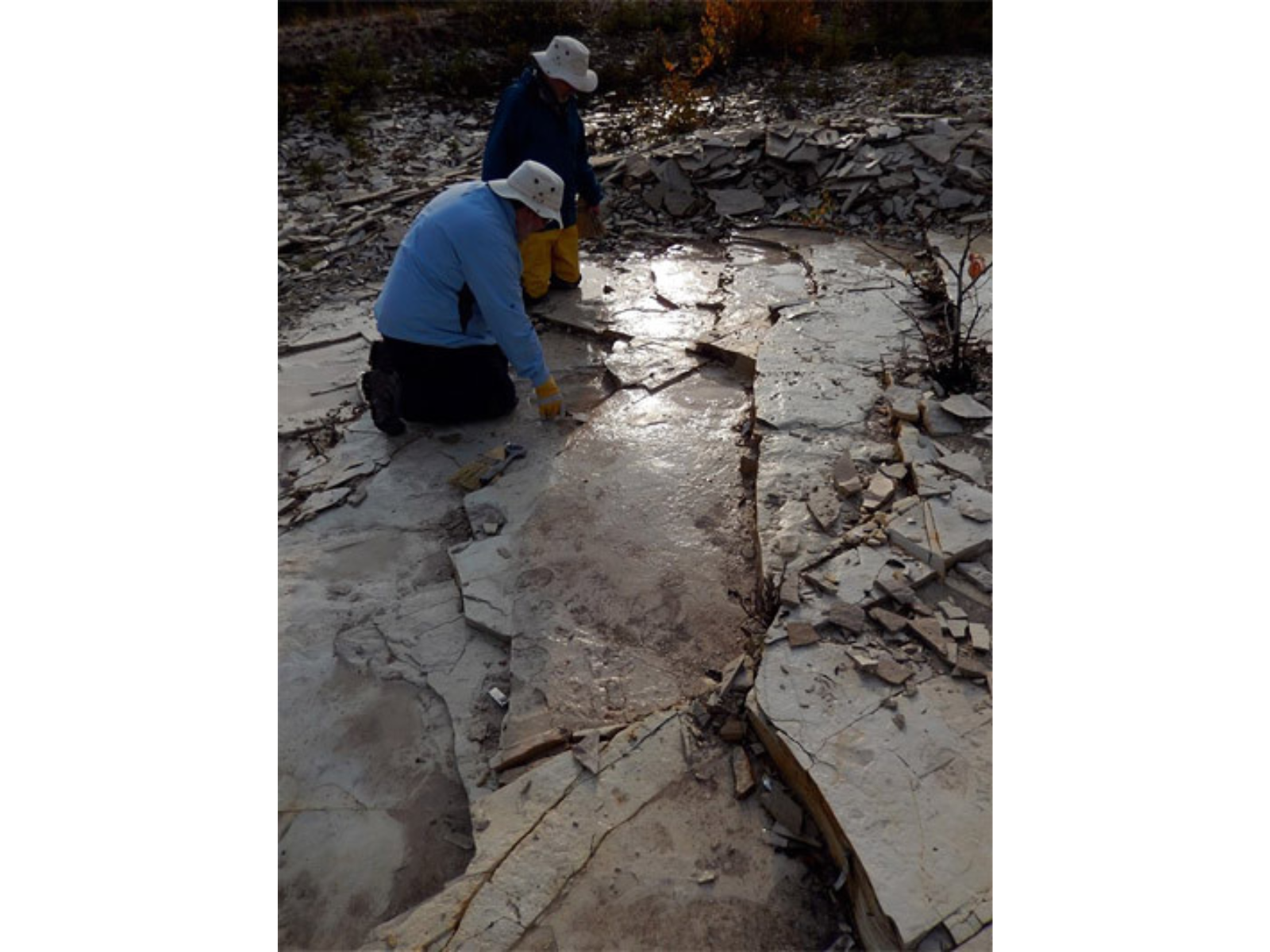

We first arrived at the main site on Wednesday afternoon. Under a relatively pleasant overcast sky, we spent several hours splitting rock, but found little in the way of specimens worth taking back to the Museum. By Thursday morning the torrential downpours had begun. These died off by the time we arrived at the site, but we discovered that the gently sloping limestone had been replaced by a “water garden” that combined both pond and waterfall features.

Donning multiple layers for protection from the rain and chill (I recall that I was wearing a t-shirt, flannel shirt, fleece, jean jacket, and rain jacket!), we swept away as much of the water as possible, then settled back into our splitting routine. The standard procedure is to place the chisel along a horizontal zone of weakness in the rock, hammer until the rock begins to split, lever it up with a pry bar, wash mud off the surfaces and examine for fossils. If no fossils are found, you throw the slab onto the discard pile and start again. After an hour or two this becomes wearying and repetitive. By the time the heavy rain returned at 2 pm, at least some of the chill from the rock surface had transferred itself into my knees and back, and I was grateful that we could stop.

Image: Michael and me, at work along a damp bedrock surface (photo: Dave Rudkin, Royal Ontario Museum)

By Friday the rain had ceased, but much of its moisture seemed to have attached itself to any clay that remained on and adjacent to the bedrock, resulting in large patches of wonderfully glutinous mud. Our crawling in this mud was at least worthwhile, as we came upon an area of rock that was very rich in fossils. We hauled out nine partial eurypterids (“sea scorpions”), along with other associated bits and pieces. By the end of the day Michael and I looked rather disgusting, encrusted with mud as we were. We were also disgusted with Dave, because he somehow managed to avoid getting mud on himself!

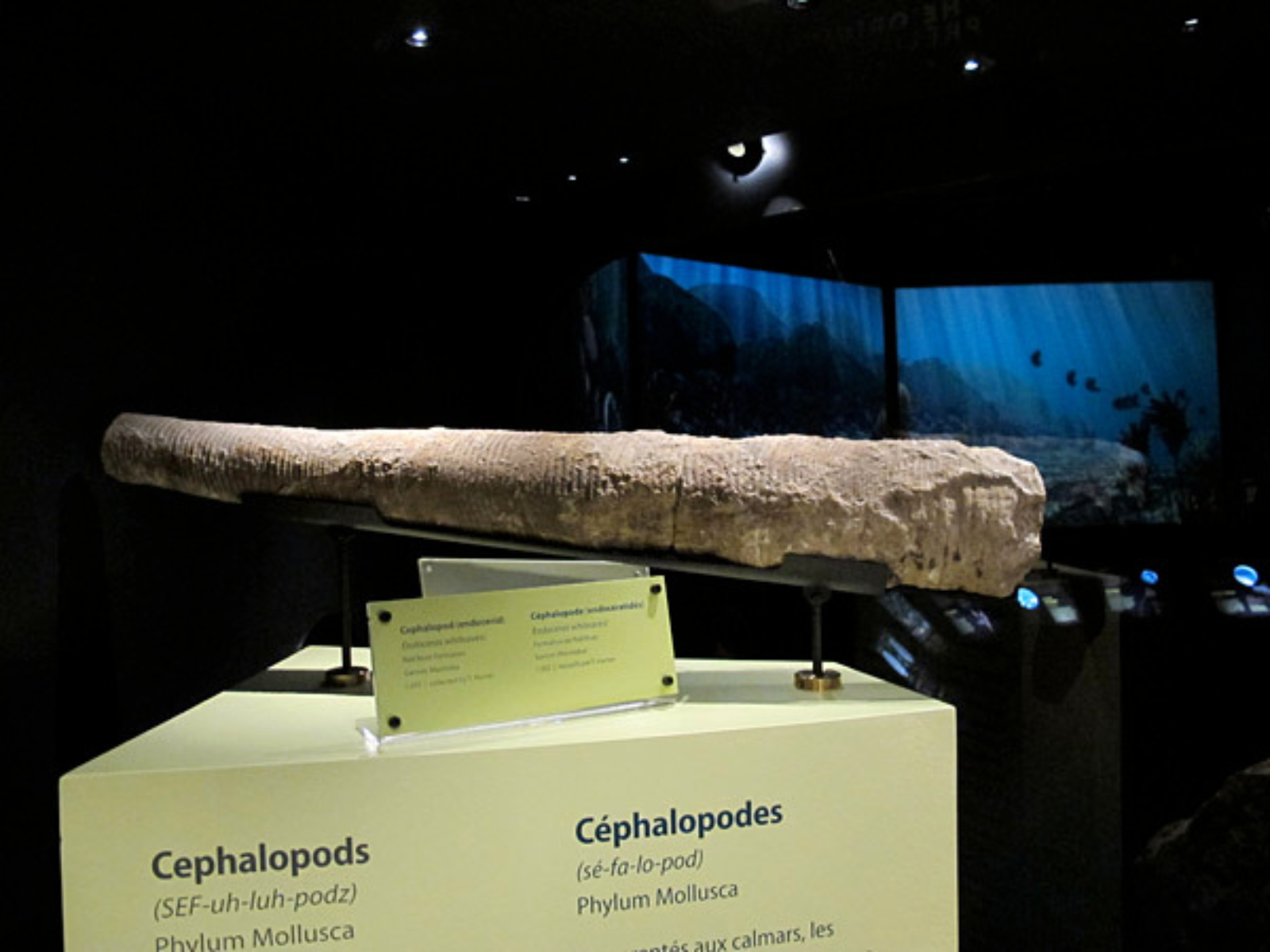

An Ordovician eurypterid from the Grand Rapids Uplands (specimen I-4036B).

Dave and Michael stand by the cluster of eurypterid-bearing slabs.

Saturday we had planned to do quick stops at several sites, prior to returning to Winnipeg in the afternoon. Of course, by now the weather had improved and we were greeted by a sunny, mild day with patchy cloud. Nevertheless, we were not unhappy that we had finished heavy collecting on the main site, as the blackflies had returned in profusion.

So if paleontologists tell you they are off to do fieldwork, you should not immediately imagine a romantic, exciting “dig”, in a setting reminiscent of that at the start of Jurassic Park. The specimens are often worth the pain, but the pain is often genuine!