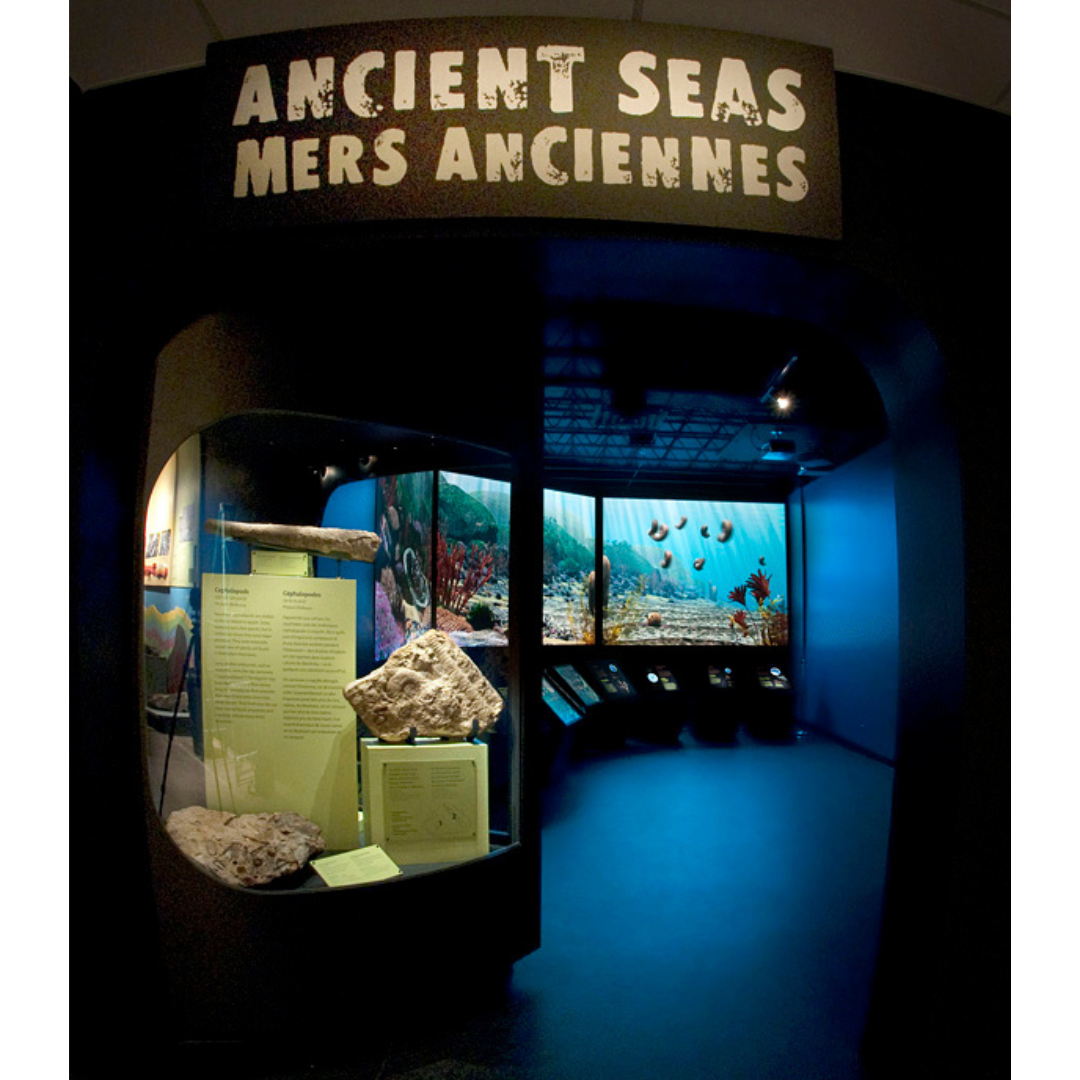

By Dr. Graham Young, past Curator of Palaeontology & Geology

If you think about how Museum paleontologists get fossils, you might guess that we go out and find where the fossils are, extract all of them from the rock and sediment, and return them to the Museum. Certainly that is what we do where fossils are scarce, but in many instances our job really consists of deciding what to leave behind. Our specialists at the Manitoba Museum are called curators, and a curator by definition has to be able to select what is needed for collections and exhibits.

Our field group, walking across dolostone beds in the Silurian part of the cove.

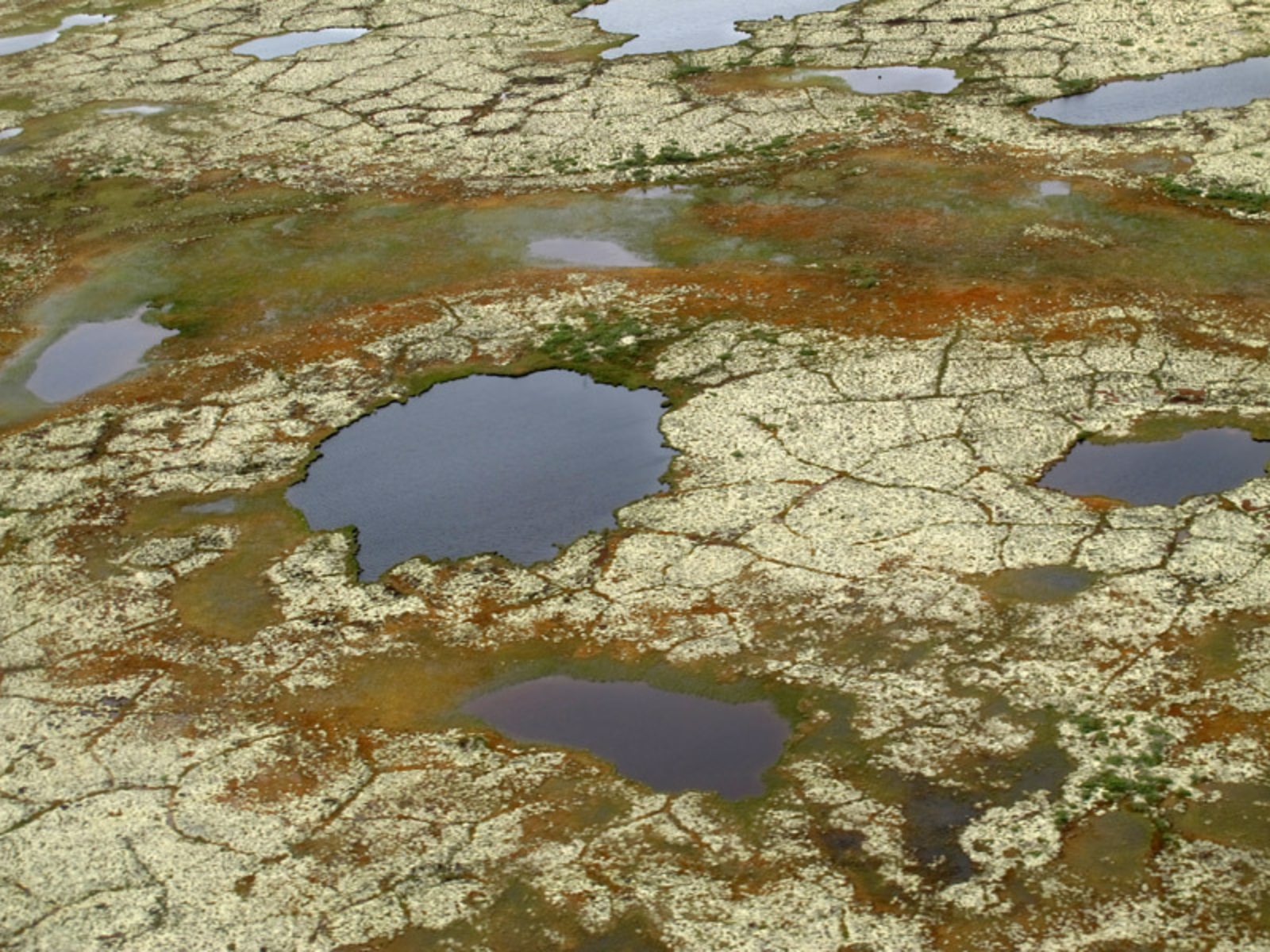

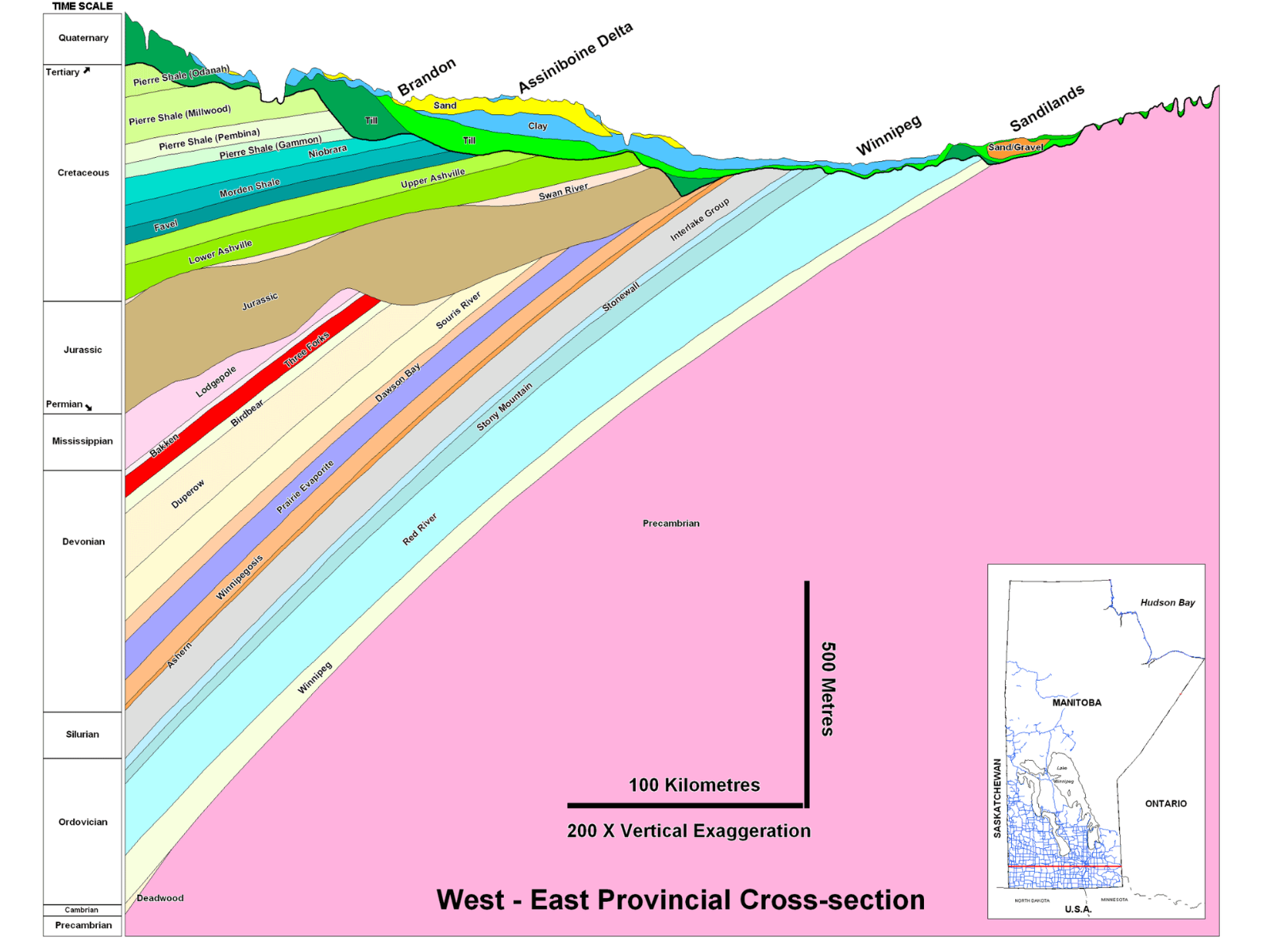

This fact was really brought home to me in the past couple of weeks, as we revisited sites in Airport Cove, the stretch of shoreline north of the airport at Churchill. Airport Cove covers a large area, with many patches of bedrock spread across the shoreline. These patches of rock allow us to sample many different sedimentary beds from the end of the Ordovician Period and the beginning of the Silurian Period, roughly 445-435 million years ago.

In the cove, the rock seems to go on almost forever.

The rocks in the cove were deposited as sediment in warm tropical seas, so fossils are plentiful in many of them. With such an embarrassment of riches we have to be selective every time we go out in the cove; if I collected every decent fossil, we would need an entire freight train to get them to Winnipeg! And then, where could we possibly store them?

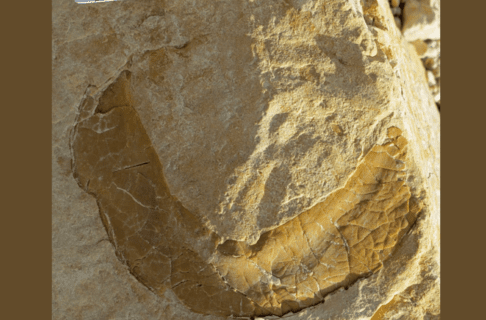

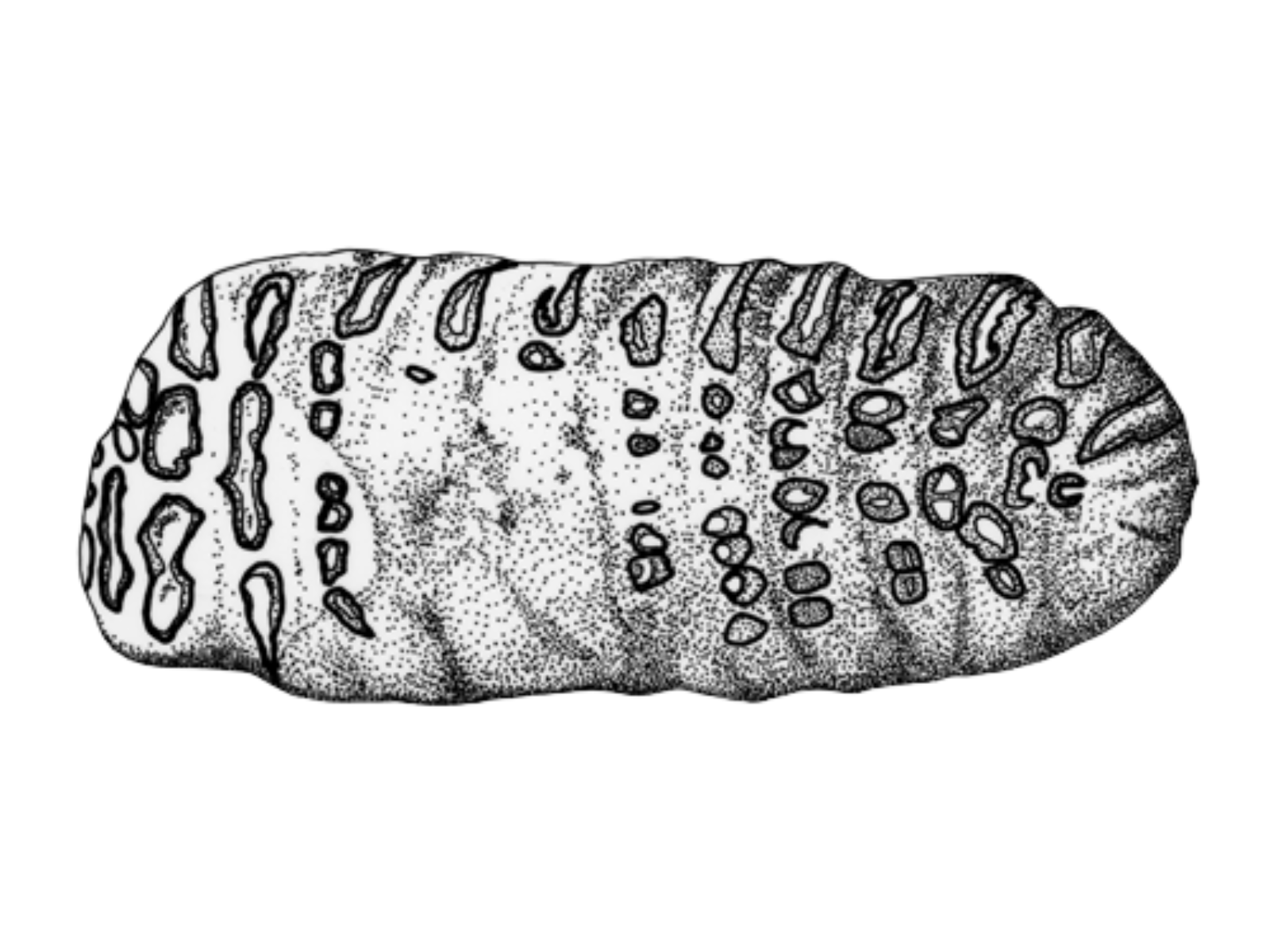

Two examples of the large Silurian brachiopod (lamp shell) Virgiana decussata.

As a result of our previous work here, many examples of the “standard” fossils from Airport Cove are already resident in the Museum’s collections, and this time we were looking for very specific and rare things. So we would walk around the cove each day, considering and photographing the more common sorts of fossils. Some of these are old friends, on blocks of stone that I can remember being in the same place ten or fifteen years ago. Others were new to me, but I can hope to see them again if I get back here. And then there are the few fossils that are so good that they must go to the Museum; one of these is shown at the end of this piece.

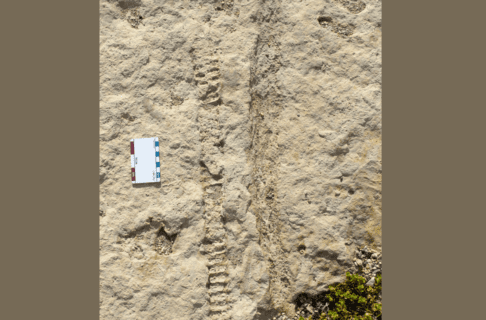

Abundant pieces of auloporids, Silurian “organ pipe” corals, in a dolostone bed low in the modern intertidal zone.

If you are ever in the Churchill area and wish to go looking for fossils, please follow all guidelines on polar bear safety! We had to leave our work area at Airport Cove twice last week as there were bears nearby, and on one occasion a mother and cub walked right through our site very shortly after we got into the truck.