Posted on: Thursday May 3, 2018

I was watching an old episode of “The Big Bang Theory” and Sheldon asked Stephanie what her favorite fruit was. Stephanie said “strawberries” to which Sheldon replied “technically NOT a fruit”. My daughter turned to me and asked “is that true” and I said “yes, sort of.” Let me explain why.

Plants have sex. The evidence of their many dalliances lands on our lawns and patio furniture in the form of pollen in the spring and later on in the year as spores, seeds, and fruits. What’s the difference between these structures? Well, pollen is like sperm in a tiny ping pong ball, a spore is like a naked baby, a seed is like a naked baby with a bottle and a fruit is like a baby with a bottle wearing clothes (or sometimes even driving a vehicle). So at this point you’re probably thinking, “Eeww, I’ve touched that stuff” but let’s cut plants some slack cause if they didn’t have sex, they’d go extinct and that would be bad for us given that we can’t photosynthesize!

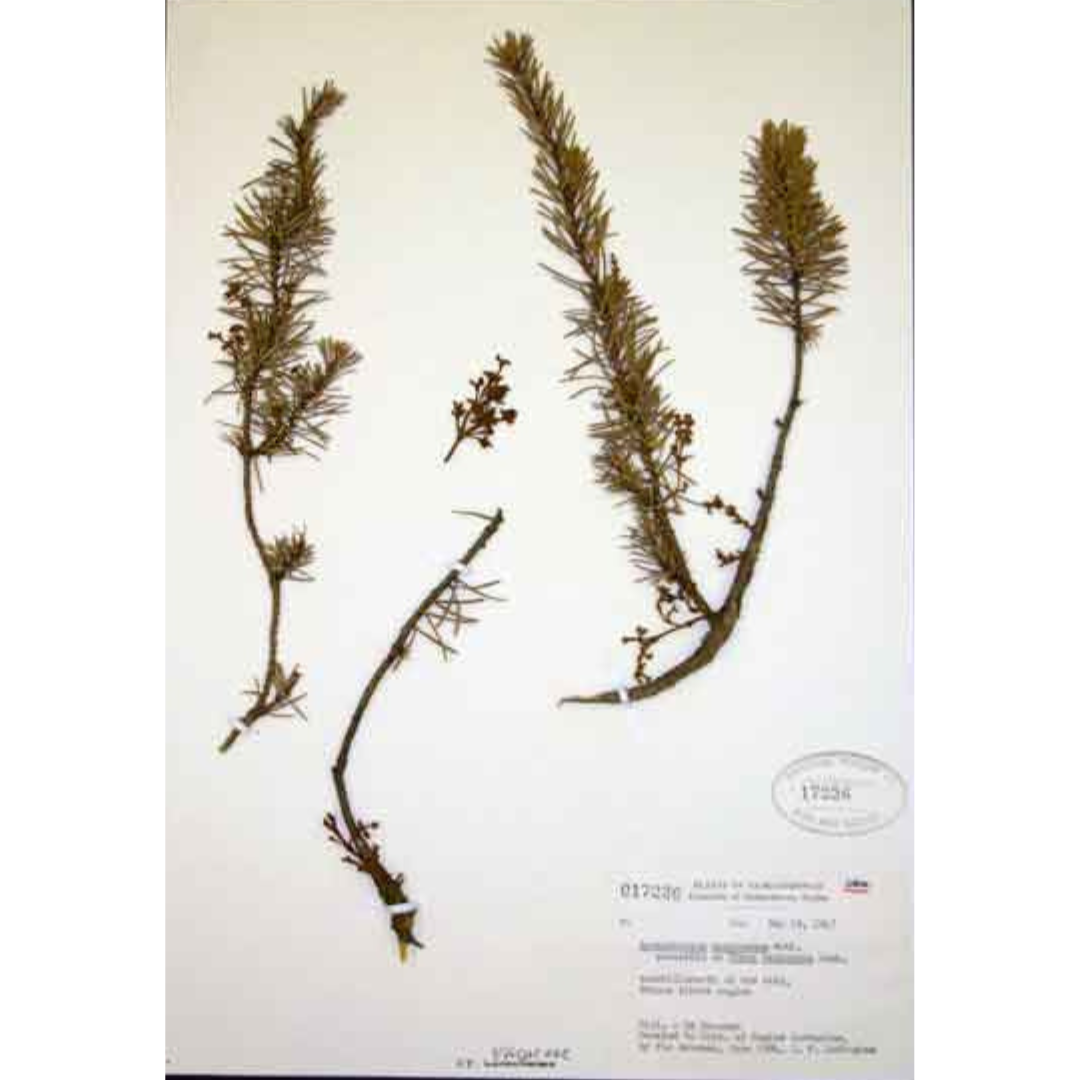

Spore-producing plants, including mosses and ferns, are terrible parents: they just abandon their children to the whims of fate with nothing to eat and not a stitch on their backs! Cone-bearing plants (=gymnosperms) like spruces, pines, and junipers, are better parents as they provide their babies with something to eat. Giving their babies a source of food enables these plants to grow in drier, less fertile habitats than spore-producing plants can. However, as their babies are “naked” with no protective covering, they are vulnerable to thieves that want to steal their “bottle”: animals!

Ostrich ferns (Matteucia struthiopteris) aren’t the best botanical parents.

Conifers like this pine (Pinus) provide their babies with food.

Flowering plants (=angiosperms) include most of the plants we are familiar with: grains, fruit trees and yes, strawberries! These species don’t let their children go out without a snack and a coat on. However, not all fruits are fleshy and edible as we are accustomed to think. Nuts are actually a type of fruit with a hard shell to protect the baby from hungry animals, kind of like a tank. Grasses give their babies clothing that sticks to their bodies and won’t come off. Maple trees give their kids hang gliders to help them soar away from their parent on the wind!

There are a variety of fleshy fruits as well. A berry is a multi-seeded fruit that includes some plants that we call berries, like blueberries and Saskatoon berries, but also some that we don’t think of as berries, like grapes and tomatoes. Raspberries and blackberries on the other hand, are not true berries, they are aggregate fruits: basically a bunch of tiny fruits clustered together on the enlarged tip of the flower stalk. Stone fruits have a single, hard seed (=drupe) inside; they include peaches, plums, and cherries. Citrus fruits are berries with a tough, leathery rind called a hesperidium. These fruits, according to Sheldon are “true” fruits.

Manitoba Maples (Acer negundo) provide their children with a vehicle. From Wikimedia Commons

Raspberries (Rubus pubescens) aren’t berries: they are aggregate fruits.

Many of the others things we call fruits actually consist of both the fruit AND parts of the flower petals. The fleshy part of apples and pears (=pome) that we eat is not actually the fruit; those are enlarged fleshy petals. Only the “core” of an apple is actually the fruit. The fleshy part of a strawberry is actually formed from the enlarged base of the flower stalk called a receptacle. Each of the “seeds” on the outside of a strawberry are actually one-seeded fruits with a thin, dry covering called an achene. So when you eat a strawberry you ARE eating the fruits of the plant, but it isn’t the part you think it is. For this reason, botanists call these types of fruits “accessory” fruits. Regardless of what part you eat though, there is one thing that is indisputable: fruits are one of the best things you can put into your body. Enjoy strawberry season everyone!

Image: The fleshy part of a strawberry is actually an enlarged flower stalk. The things on them we call “seeds” are actually the fruits.